When it comes to speculation, it makes sense to do some research before second-guessing any maritime mishap. And with this in mind, Ive spent the last couple of months sorting through statements, Race Control press releases, and information deduced by the authors of the Volvo Race Independent Report (VRIR) into the stranding of Vestas Wind.

For those who missed the news of the Vestas Wind shipwreck, heres the short version: In 2014, one of the best-equipped, best-crewed, best-skippered boats in ocean racing, competing in the prestigious, around-the-world

Photo by Brian Carlin/Team Vestas Wind/Volvo Ocean Race

Volvo Ocean Race was flung up high and dry on a well-charted reef in the Indian Ocean on Nov. 29. The accident occurred during leg two (Cape Town, South Africa to Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates) of the nine-leg race, which finished in Gothenberg, Sweden, in late June 2015. Fortunately, no one on the boat was killed or seriously injured. The Volvo Races 80-page independent report, released earlier this year, set out to determine the causes of the accident as well as offer measures that should be taken to prevent such accidents from ever happening again.

The report is a comprehensive summary of what led to the grounding, and it alludes to shortfalls in the role of the navigator and skipper. In our review, we explore these errors in more detail and look at how, even with a state-of-the-art electronic navigation network onboard, operator error can still lead us astray.

One of the unique elements of this particular accident was that it was recorded by a fixed-mount cockpit camera. Just Google Vestas Wind shipwreck video, and youll watch the drama unfold in various stages, from wreck to recovery of the vessel.

It is clear by watching the moment of impact that no one aboard had any idea the boat was approaching a surf-swept fringing reef. The Bruce Farr-designed VO65. charged into the surf zone at 19 knots, snapping off the leeward dagger board as if it were a toothpick. Pounded by waves, the rudders were ripped from the hull, and the stern quarter was pulverized.

The three golden rules of navigation are fairly straightforward: Know where you are, know where youre going, and know whats in the way. The navigator and skipper aboard Vestas Wind had the first two down cold, but somehow the third slipped from their grasp.

Immediately after the accident, the second-guessing began. The incident unfolded with sensationalized reports of uncharted reefs and technology being incapable of delivering the goods; but from the start, the likelihood of operator error lurked in the background. And like most accidents at sea, there was a range of contributing factors involved, and getting to the bottom of what really happened was a puzzle with pieces that went back to the last-minute sprint to get the boat ready to go.

Background

Bad luck can turn minor missteps and omissions into real trouble, but the plight of Vestas Wind came with a long history. In some ways, the shipwreck was like a Daytona 500 race car driving smack into the wall on a straightaway, an unlikely incident that pros are expected to avoid.

Contributing factors started piling up well before the VO65 sailed into Indian Ocean waters. Feedback from interviews and pre-race calendar waypoints show a program that was late in its formation and pressed for time right up until the starting gun. There were last-minute vessel prep issues as a crew of capable pros came together with little time to spare.

During the first leg, the four-hours-on/four-hours-off watch routine kept the three-person watch fully engaged with sail trim and go-fast demands aboard a boat being sailed like a Melges 24 on a 24/7 basis. This put especially high demands on the navigator and skipper, who floated between three-hour watches to fill out the crew.

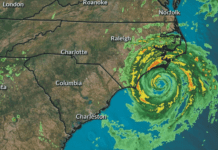

The Indian Ocean leg presented competitors with more than a wind and sea challenge. Security concerns also had to be factored into the equation. The Volvos Race Control had responded to the threat from Somali pirates by implementing an exclusion zone that acted as an impenetrable barrier to keep competitors east of coordinates near the African coast. Unfortunately, a tropical cyclone moving across the Indian Ocean caused this pirate barrier to be modified, allowing racers to transit the waters surrounding the Mascarene Plateau.

This change in routing allowed each crew to redefine its northeastward route. All this occurred as competitors faced a challenging leg that began in Cape Town, and included a crossing of the Agulhas Current, a close reach into prevailing tradewind seas, and a sprint to clear the southern tip of Madagascar.

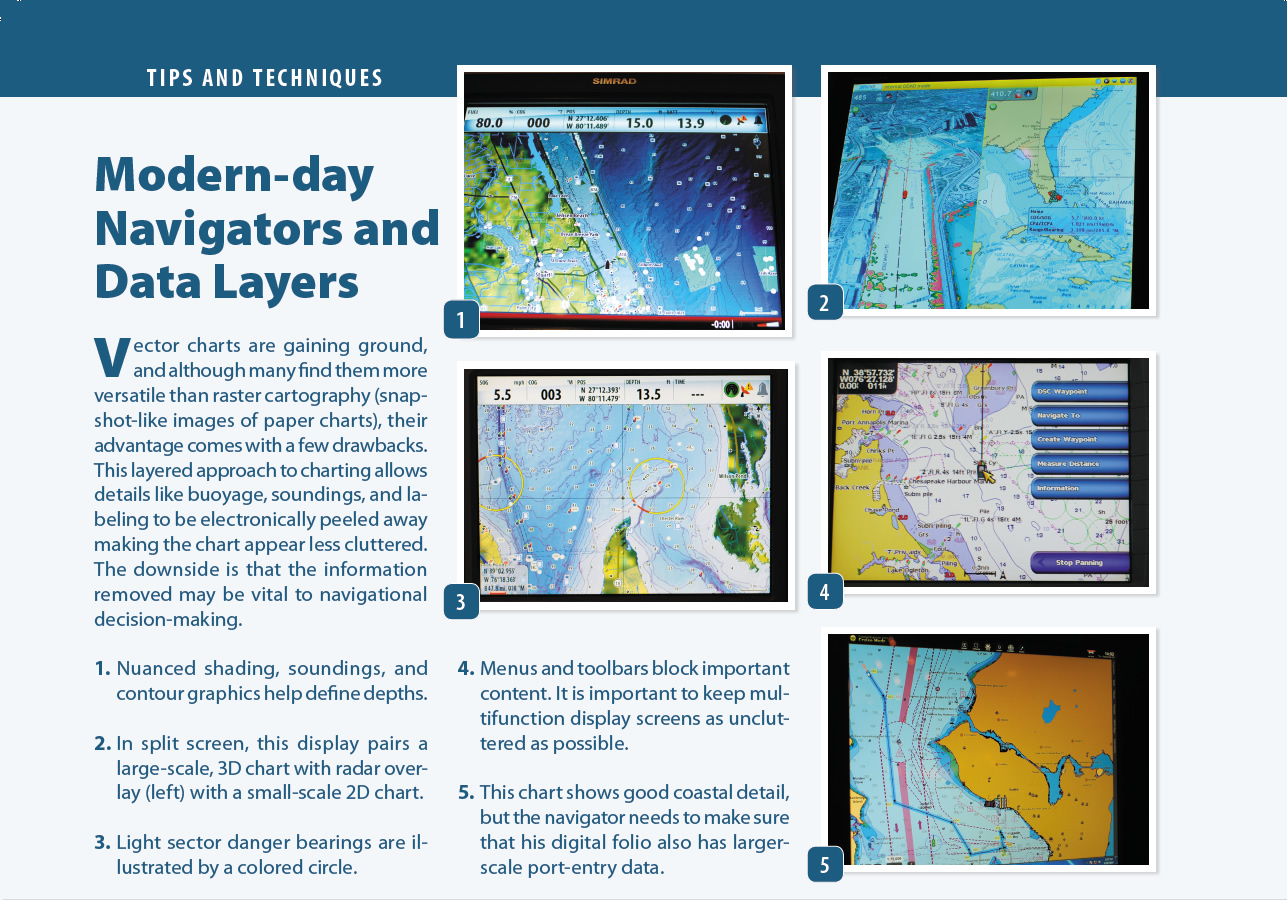

Each boat had an impressive array of navigation equipment. The list included a B&G Wave Technology Processor CPU (WTP3), two Zeus 7 multifunction displays (MFDs), two Panasonic laptops, and a 10-inch Panasonic Toughpad. The essential software included Expedition, Deckman, and Adrena. The kit also included B&G 4G radar, sounder, and electronic compass. To round out the navigation package, each boat carried a C-Map dongle packing a full array of large-scale, detailed charts. Aboard Vestas Wind, it appears that the detailed cartography was used on the laptop running the Expedition software (used for profiling performance), while the weather and routing was done on the laptop with only small-scale charts.

The VO65 is a refined high-tech ocean racer designed to be handled by a smaller crew. Aboard Vestas Wind, all nine hands pitched in when it came time to make major sail changes or other complex sail-handling maneuvers. Otherwise, the versatile sail plan (with three headsails on furlers always ready to be deployed) allowed the standing watch to handle sail changes on its own. At the time of the grounding, the breeze was up and the crew was engaged in pressing on at slightly less than 20 knots.

Familiar Waters

The perspective I offer is far from just another opinion of a land-based mariner second-guessing decisions made by others at sea. Its from a sailor who sailed his own boat to the Cargados Carajos Shoals a few decades ago, using a sextant and paper charts filled with soundings made by Captain Cook and his intrepid crew. The irony is that despite the six-digit array of electronic navigation and communications gear aboard Vestas Wind, shore-side support (including 24/7 tracking), and a full-time navigator, the Vestas Wind crew somehow remained unaware of Mascarene Plateau-a chain of surf-swept shoals dotted with deep spots that make up a 1,000-mile-long obstacle to navigation.

These fringing reefs and islets climb like coral-ringed mountaintops from the depths of the Indian Ocean and run from Mauritius in the south to the Seychelles in the north. They are clearly described in the races Sailing Directions, even depicted on the Indian Ocean page of the National Geographic Atlas of the World. I mention this wonderful landlubbers reference because it drives home that the Cargados Carajos Shoals are anything but uncharted reefs. Sailing into the Indian Ocean unaware of the Mascarene Plateau is like going for a cross-country bike ride unaware that youre about to meet the Rockies.

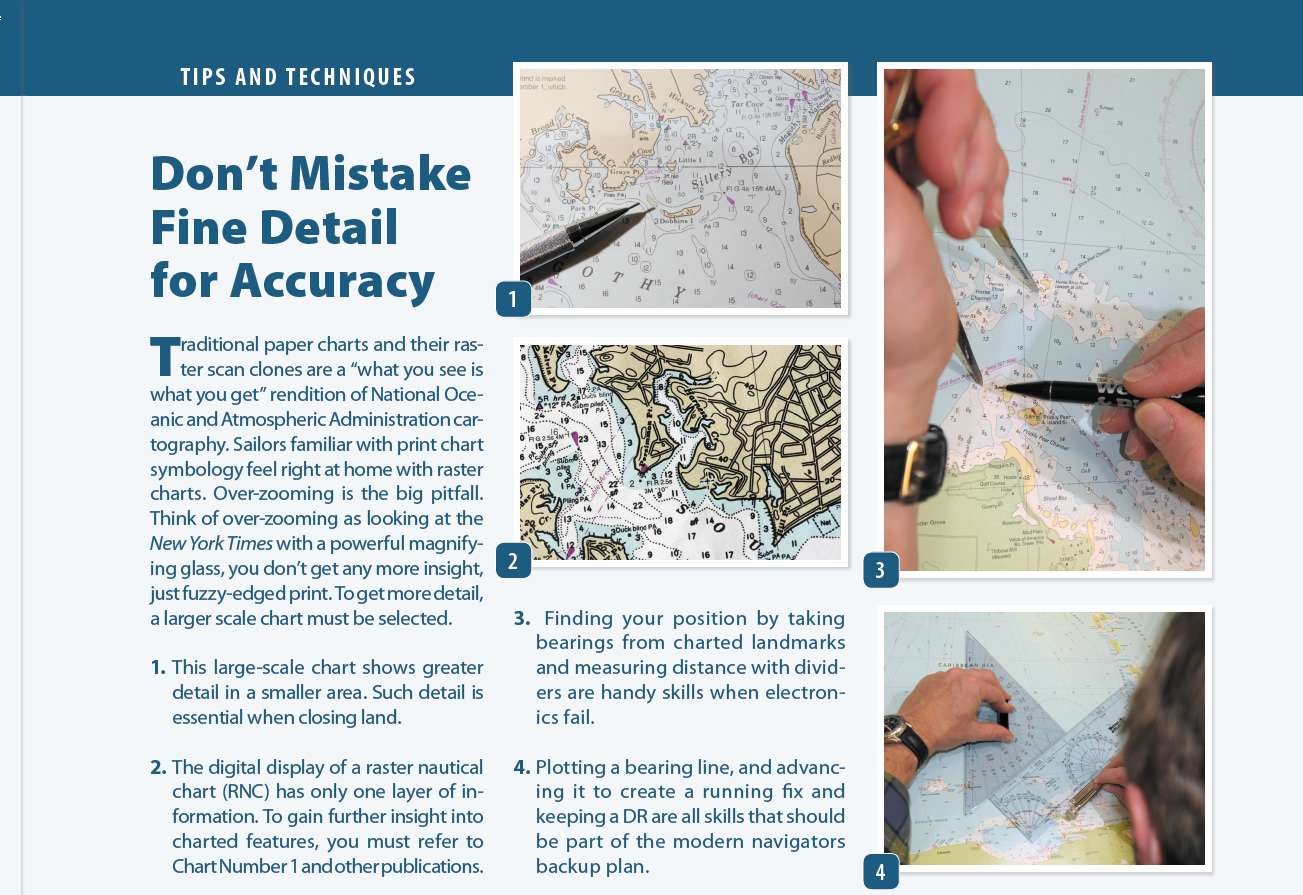

The nautical charts available to every competitor in the Volvo Ocean Race held ample detail, however, it did require the selection and use of mid- to large-scale charts when approaching the shoal waters. A navigator or skipper noting depth changes going abruptly from 5,000 feet to 150 feet would be expected to automatically switch to a more detailed, larger-scale chart in order to clarify soundings in the shaded boundary. Route planning using only a small-scale chart, is like looking backward through binoculars-the details disappear.

Justifiably, the Volvo report pointed to the crews complete unawareness of the shoals existence as the reason why the incident occurred. This absolute lack of awareness resulted in the navigator being asleep and the skipper engaged in the boat-handling routine just as they were approaching the blue blobs on the small-scale chart. If just one of the Zeus B&G MFDs was displaying a digital chart, or the laptop with the detailed C-Map cartography dongle attached was displaying a mid- to large-scale chart, the threat would have been obvious.

When it comes to contributing factors, my findings and the VRIR diverge somewhat in the proportionality of cause. They list two issues: deficient uses of electronic charts and other navigational data, and deficient cartography in small, mid-zoom, and over-zoomed situations. Though the latter existed, its role was minor compared to the shockingly deficient navigation procedures onboard. Basic navigation training underscores why one uses large-scale (small-area), detailed charts to define hazards. Omitting that step is not the fault of the cartography.

The rest of the fleet cleared the shoals without incident using similar hardware, software, and cartography. There was certainly enough detail in the digital charts on board to become fully aware of the hazard and navigate around it safely. Although the independent report hardly absolved the skipper and navigator of blame, by not stressing that 90 percent of the cause was operator error, and perhaps 10 percent could be attributed to cartography, the report points the finger in the wrong direction, in my opinion.

Conclusion

The need to be diligent 24/7 is a daunting task, and one that keeps short-handed cruisers constantly tracking their risk-assessment priorities. The navigators threefold refrain remains the same as it has always been: where are we now, where are we headed, and what lies in between?

Cruising sailors are often solo watchkeepers. Vessel safety, collision avoidance, and staying afloat are at the top of our priority list.

Racers rearrange these priorities with number one being to keep the boat making the most progress possible toward the destination. Number two is to use all data available to make tactically advantageous navigational decisions. As a result, safety has inadvertently slid down the list.

Aboard Vestas Wind, the dominos fell one-by-one, and began with little things like neither the skipper or navigator reading the Sailing Directions for the region, which clearly allude to the Mascarene Plateau and its 1,000 miles of scattered reefs, sand shoals, and islets. The least useful, small-scale display of C-Map digital charts was apparently being used for route planning, and the big blue blobs showing 200-foot depths rising up from a deep abyssal plain were so innocuous, they didnt prompt a closer look.

The navigator and skipper apparently focused on performance, and let days worth of opportunity to change the outcome slip by. When only miles separated the Cargados Carajos Shoals from the big VO65, the navigator was asleep in his berth and the skipper was helping the on-watch crew push the knot meter toward 20 knots. No, this shipwreck had nothing to do with Dilution of Precision or Zone of Confidence in the cartography-it was a sad case of operator error and a reminder to us all how important it is to always know all three answers to the navigators refrain.