Old Salt’s Anti-chafe Solution

Being a team of diehard do-it-yourselfers, we decided to try our own hand at devising a workable solution to defeating line chafe. After fiddling with canvas, old fire hose, and even messing around with some Kevlar, we settled on leather—an old rigger’s standby. It proved to be rugged and remained unholed after a ride on the belt sander. The fabrication process was kids craft 101, and there was something quite seafaring about the result. …

Old Salts Anti-chafe Solution

Being a team of diehard do-it-yourselfers, we decided to try our own hand at devising a workable solution to defeating line chafe. After fiddling with canvas, old fire hose, and even messing around with some Kevlar, we settled on leather—an old rigger’s standby. It proved to be rugged and remained unholed after a ride on the belt sander. The fabrication process was kids craft 101, and there was something quite seafaring about the result. …

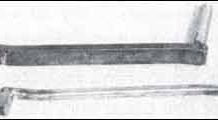

Design For: Winch Handles

Making spare winch handles is a simple job for a competent metal worker. This I discovered because our Norlin designed Scampi, Windhover, has eight winches, all of which were manufactured before the world standardized on the 11/6" winch handle lug size. Since Windhover's 9/16" size handles are difficult to obtain and impossible to find at discount I went to Frank "Red' Grobelch, a superb metalsmith/welder of Waukegan, Illinois with some ideas for making up some spares for me. I'm so pleased with the results that I'd recommend the project to any reader who is a competent metal worker or has a friend who is. Even if you can use and buy standard 11/16" size handles, your mental state when clumsy Uncle Fred drops a handle overboard will be far more buoyant if you know you can easily replace the lost handle in your own shop.

Design For: Cockpit Foot Brace

Modern yachts are frequently advertised as having spacious cockpits: and, indeed, they do. But it doesn't take many afternoons of sailing to discover that the cockpit which seemed so splendidly roomy in the showroom or at the boatyard is too damned wide: it's impossible to brace your legs across the footwell without sliding down so that your body only contacts the boat at shoulders and tailbone. If you want to sit on the cockpit coaming while steering there's no place at all to brace your feet.

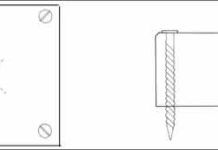

Metal Chafe Plates: Functional Remedy for Scrapes and Scratches

What do you do when the pin in the leg of your folding cabin table digs up the cabin sole? What do you do about the groove in the top of the teak toerail caused by your dock lines? What about the scuffs in the varnished bulkhead behind the companionway ladder? The answer is that you make chafe plates to solve all three problems. While chafe plates can be made out of almost any material — sheet PVC, thin stainless steel, aluminum — the most readily available and easily worked stuff is plain old brass. Brass can be purchased in many forms: sheet, solid round bar, pipe, tubing, and half oval, for example. It is quite cheap. If you have a local scrap metals dealer, you can buy enough scrap brass in various forms for $10 or less to keep you busy with a lifetime of projects. If there's no metal dealer at hand, most hobby shops carry substantial supplies of brass, although hobby shop brass tends to be thinner than what you want for most jobs.

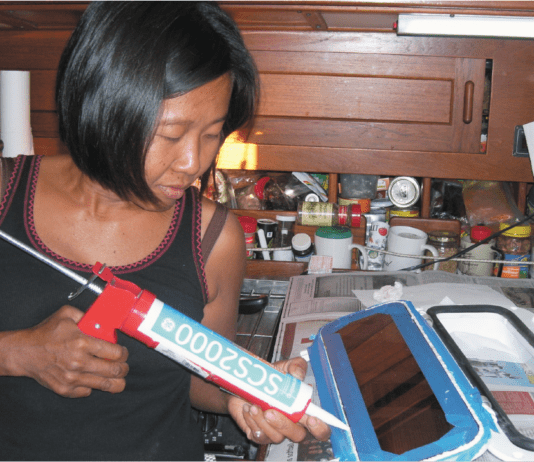

Design for: Through-Deck Fittings for Coaxial Cable

Sealing the holes in decks where Loran and VHF antenna cables penetrate is a fairly common problem on modern boats. If there were only the cable to be considered, a hole of the appropriate size plus a dab of sealant would do an adequate if tacky looking job. But these cables inevitably include sizable end connectors which require holes much larger than those required for the cable itself. Solutions include removal and reinstallation of the connector each time the cable is removed during storage or servicing, and any number of commercially available through-deck fittings or plugs. None of these solutions is simpler or better than the wood fitting shown here. It is attractive and can be made in a few minutes for a few cents.

No Supermarket At Sea

Cooking at sea has never been easy and is usually looked upon as a dull, but necessary task. Nothing can spur the queasy stomach to open rebellion more effectively than going below to a hot, stuffy galley to prepare , ugh! - food. Why would anyone in his right mind try to prepare a meal at a 30' heel while the rest of the crew enjoy a sail on deck? The term, 'slaving over a hot stove', takes on new meaning. Yet, the cook is a vitally important member of the ship's crew, and it is not an easy job. Whether on a delivery, racing or long distance cruising, a non-stop passage on your boat means no nipping out to buy that missing ingredient: there are no supermarkets at sea! So remember, the moment you leave the dock you'd better be sure you haven't forgotten anything. If you like acronyms, here are two secrets to success that you can remember: The Six P's, and MAMAS Theory.

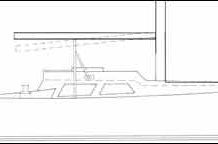

Taming the Wild Boom: Two Designs for a Gallows

A wildly flailing boom is one of the most dangerous objects aboard a sailboat. If you could completely control the boom at anchor and under power, and while raising, lowering, and reefing the sail you'd avoid worry, save energy and be much safer. For this reason, many serious cruising boats have traditionally carried permanent boom gallows. They usually take the form of metal pillars bridg ed across the top by a wooden cross member. Bolted to the deck at the aft end of the cockpit or on the aft deck itself, they serve several functions: holding the boom firmly when the sail is down; catching the boom easily as the sail is lowered; and, perhaps most importantly, keeping the boom steady during reefing operations.

Design For: Tableware Storage

One solution to the problem of tableware stowage is a bulkhead rack of the type commonly available from marine chandleries and discount houses. If you have some free bulkhead space in the galley area such racks can be fine, but, if you've got a drawer or cupboard available, stowing your tableware under cover seems a better solution. The problem is that the tableware should be secured within the drawer or cupboard. You could use one of the compartmented, plastic trays such as many of us employ at home, but ideally you want something which holds the tableware against the movement and vibration of the boat.

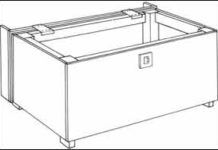

Design For: A Dock Box

Whether by choice or force of circumstance, increasing numbers of us are sailing out of marina slips rather than off moorings. For anyone using a slip or dock as home base, a dock box is a handy receptacle for spare lines, fenders, paint, varnish, tools, and miscellaneous gear. Also, a solid dock box can make a useful, if low, work bench, and sometimes serves as a step for a boat with high topsides. The smallest, lowest priced, commercially available dock boxes sell at discount for nearly $200, and the cost can go up to over $300. Hence, making a box yourself can save you a good deal of money. The illustration shows the construction of a basic, plywood-skinned box with notes on material sizes or scan't- flings. As you can see, construction is simple enough so that even a beginner can make a good job of it.