For most sailors the off-season begins on Labor Day, which is a shame because fall brings the best sailing of the year in many of parts of the country. Of course, extending the season also brings the risk of snow and ice on deck.

When the water turns hard, details matter. Frozen lines can jam, decks get slick with frost, and even minor heating and ventilation problems can be miserable or destructive. But assuming your preparations were thorough, there are pleasant days for sailing throughout the year.

Photos by Drew Frye

At Dock

In saltwater, ice encroaches at different rates. In tidal areas the water seldom freezes, although less saline harbors ice-in before others. For example, in Deale, Maryland on the Chesapeake Bay there are two creeks: the north branch gets good tidal flow because the creek is long, and seldom freezes, while the southern fork goes only a short distance, experiences less flow, and freezes sooner, thicker, and for longer. A flight over the Chesapeake in mid-winter tellingly reveals this.

De-icers. While a bubbler wont free the channel of ice, many use them to keep the area around their boat ice-free. For me this is often the difference between getting to the channel or not. However, damage from a few inches of stationary ice is exceedingly rare and bubblers are not needed for thin ice. The greatest risk factor is moving ice, and for this you must depend on local knowledge. If the marina is vulnerable to moving pack ice during the spring thaw, the only safe solution is to haul out.

Photos by Drew Frye

Sump pumps. No loops or check valves. They must be free to drain back to the sump, which should remain ice-free as long as the boat is in the water. If any water remains in the line it will freeze and the sump pump will not function.

Engine Exhaust and Bilge Pump Outlets. These must be well above the waterline. When loaded up with snow, a boat can easily sink 2-4 inches below the normal load line; boats sink every heavy snow year. Additionally, the bay is less salty in the winter, causing boats to ride as much as 1-2 inches below their summer lines. Thus, all open discharges should be at least 6 inches above the water line. Several winters ago a power boat in my marina went down because the exhaust ports were pushed under by snow load, there was a small leak in the piping, and the bilge pump failed (a loop in the discharge line allowed it to freeze; the pump ran continuously, but to no benefit).

Refrigeration. Even in the coldest weather, we use a plastic cooler, sometimes left in the cockpit. On warmer days it buffers the sun and keeps the birds out. On the coldest nights it prevents freezing.

Shovels and Brooms. A plastic shovel-one of the small folding ones sold for the trunk of the car-works for me. It safe around gel-coat.

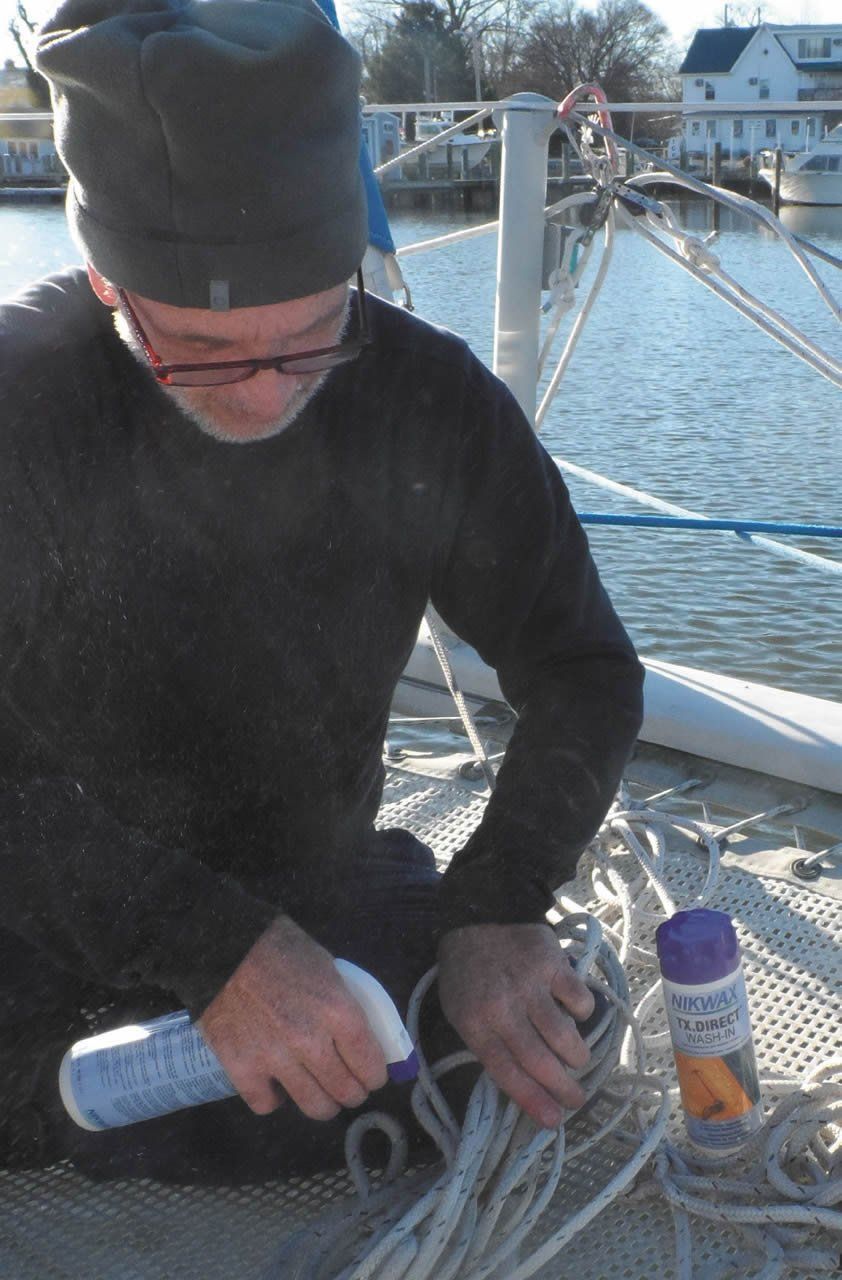

Sailing

Frozen Lines. Imagine an ice climber, inching his way up a frozen water fall, suddenly faced with ropes as stiff as a pair of blue jeans left on the clothesline in January. Unsurprisingly, they use dry-treated lines-ropes that have been treated with water repellent sufficient to prevent solid freezing. They will still absorb some water, but many times less than untreated and not enough to become stiff, lose much strength, or gain much weight. We have used wash-in Nix Wax Polar Proof for many seasons. Although the instructions suggest treatment in the laundry, there are simpler ways. For ropes that are easily removed (mainsheet, spinnaker sheets, genoa sheets), fill a bucket with the recommended solution and dunk the ropes for 30 minutes, mixing and turning several times. The product will treat several times more than the label suggests. As for more difficult lines (halyards and the very critical furler and reefing lines), these can be sufficiently treated by painting with a brush or using a spray-on treatment. Easy.

Clear the Snow. Not only is the footing bad, snow holds water and all of the deck mounted hardware will freeze over.

Sail Tracks. A coating of lubricant like Sailcoat repels most ice. Be generous, as a stuck sail can be dangerous.

Jam Cleats. These can fill with ice. Cam cleats and horn cleats are more reliable.

Ice Floes. Faced with even the thinnest layer of ice or floes, I return home for fear of prop damage; even thin ice will be pressed under by the forward motion of the boat and into the prop, which is not made for chopping. Often the Coast Guard issues warnings, closing some areas to recreational boating during the spring thaw. Unless you have polar ambitions, its best not to challenge nature.

Smaller Sails. I switch to a smaller self-tacking jib for winter. It is generally windier in the winter and I don’t press as hard either. Spray is cold, the air more dense, and I reef earlier.

Engine Starting. Some are outboards are dependable; I loved my old Nissan 18 hp 2-stroke. My current pair of Yamaha 9.9 4-strokes require full choke and a little priming, but catch within a few tries even after weeks. Do allow for a longer warm-up. Fortunately there is a silver lining; cold air actually helps with E10 induced enleanment (winter air is denser, with 10 percent more oxygen than mid-summer) and run with better power once warm. Running the engines for 15 minutes every few weeks though the winter should be good for them, keeping fresh fuel moving through the train and oil on the cylinder walls.

Power consumption. Battery voltage is reduced by low temperatures. Keep an eye on this and know the minimum voltage that will start the engine. Solar cells will generate less because gray days are common, the sun angle is low, and days are short. Longer nights mean more lighting and more entertainment amps. Dont run instruments you don’t need. Hand steer a little more. For a typical wet cell battery, 75 percent of standard 70F capacity is available at 20F. Also note that battery voltage drops below the listed values by about 0.075 volts for each 10F below 70F, so at 20F you may only have about 12.3 volts at full charge.

Personal gear

Wet Suit or dry suit. You never know when you might have to dive to clear a line, check for damage, or face some emergency. A 3mm wet suit will do for water temperatures into the 50s, as long as youre quick about it; in the lower range it wont be fun, but it wont be dangerous.

Below that is the territory of dry suits (Soul Dry Suit. 2-Year Up-Date, PS January 2016). These have the advantage of being very wearable, even as foul weather gear, protecting the crew in the dingy and in the event of MOBs; properly fitted, a sailor will remain comfortable in freezing water for 1-6 hours, depending on the details of his clothing. If one is fitted to each crew member, they are very serviceable immersion suit substitutes for lake and coastal sailing.

Jacklines and harness. These are a safety essential in the winter. There can be no exceptions to wearing a harness in open water when single handing in the winter. The deck can be absolutely treacherous when covered with frost or a glaze of ice; if you fall in, youre a dead man.

Strength of Materials and Brittleness. Polyester, aramid, nylon, and high-tech polyethylene (Spectra, Vectran, Dyneema) are not significantly affected by low temperatures. This has been proven in the lab, in theory, and by mountain climbers, in practice.

However, sail cloth can be a bit more prone to tearing if stepped on; it seems that the finishing resin gets stiffer in the cold and that is responsible. PVC moldings become more brittle, so be careful around small latches and the like. Soft vinyl dodger windows (do not roll them below). Sails with vinyl windows should not be used below about 45F and never folded below 55F. PVC can shatter if you step on it, one more reason it should never be used below the waterline (only nylon and polycarbonate).

Ice Buoys. Some private markers are pulled for the winter. Some Coast Guard aids to navigation-particularly in the upper Delaware Bay, upper Chesapeake Bay, and Tangier Sound-are replaced by special ice buoys during severe winters. They are little bit smaller, and all of them (red, green, and black) resemble nun-buoys more than other types. They are designed to withstand the pressures of ice and to resist being pulled off station. The light is designed to withstand the vibration without the filament breaking. In reality, if ice buoys have been deployed to a certain area, you probably shouldnt be there. However, I have seen them in the spring when they had not yet been replaced.

Propeller Damage. If the ice in the harbor or on the Bay is thick enough to damage the hull, best to stay at the dock. However, in very thin ice or broken ice there is a hidden danger; as the hull moves through the ice, even if the propeller is far below the surface, sheets of broken ice will find themselves pressed far under and will be sucked into the prop. There is also the very real chance of becoming stuck even in thin ice, creating a dangerous situation. If you must press through a few hundred yards of thin, new ice to get to your slip, proceed slowly, back out and take a fresh start before you get stuck, aiming a boat-width to one side. Often your wake will start cracks in the ice. Be observant, and look for weakness rather than just gunning the throttle.

The biggest challenge in winter is having enough books and movies to get through the long nights. Perhaps youll never sail the great southern ocean or even want to. Still, you can pretend that you have and make Water Mitty proud. A winter afloat will be a miniature adventure, will give a new perspective on sailing, and perhaps breed a new found respect for the watermen who work year round.