Alazarette that closes at the wrong moment can cost you a broken finger—or worse. I should know. A failed latch on an oil field tank early in my career cost me a number of chipped teeth, a permanently wonky mandible joint, and a lovely scar on my chin (a hard hat saved my skull). The anchor locker lid on my F-24 kept blowing shut during anchor recovery, and a falling toilet lid has smacked more than a few sailors.

In addition to the personal risk of a loose locker lid or hatch, there is the risk to the vessel itself. During a knockdown, a hatch that flies open can flood the boat or cause important gear to break loose or be damaged. Racing rules require that critical hatches be strongly secured, and this makes just as much sense for cruisers.

KEEPING THEM OPEN

The mechanism for keeping hatches and locker lids open must be both reliable and easy to use, but latches are often an afterthought, poorly engineered, weak, or just plain missing. Hatch mechanisms need to be tested at sea. A hatch that stays open just fine at dock may slam shut when the boat heels or the wind blows. Hatch mechanisms must also be inspected regularly. Props, springs, or bungee cords that keep lockers opened are often under-maintained. Corrosion at an important latching mechanism once caused a locker lid to bonk me on the head.

If you are making your own hatch or locker lid, make sure it is well-reinforced where any latches, props, or hinges attach. Before sticking your head in the locker, always check that the lid is well secured in the open position and keep your fingers away from hinges. Before heading out to sea, all hatches and latches should be checked for watertight integrity. In this report, we’ll look at the various options for securing latches in the open position and discuss a couple of ways of keeping them closed.

THE 180-DEGREE HATCH

Sometimes it’s perfectly okay to let the hatch open 180 degrees and lay it on the deck. Make sure the hinge is designed for this use, of course. It is tempting to add a restraining cord to prevent the hatch from flopping into the fully open position, but this will reduce access. The cord will also create a situation where the hatch lid can accidentally swing closed, contrary to your goal.

Bottom line: This is an acceptable arrangement for hinged hatches that allow this. If you find yourself frequently wanting to close the hatch from below deck, consider adding a short lanyard, or some other means to close the hatch from inside the boat.

SPRINGS

Springs are one of the easiest ways to prop open a locker lid. If you have a 1990s-era production boat, your refrigerator lid might have one—and you may have already felt that lid’s painful pinch when you accidentally bumped that spring. The spring pops into place automatically when the hatch is opened, propping the lid up. To close, you push the spring to one side by hand. The problem with spring props (apart from corrosion in the cheaper varieties) is that they close just as easily as they open. It’s far too easy to bump the spring to the side with your elbow, the gear you are retrieving, or the gear you’re placing in the locker. The result is a hatch that slams down at full velocity. The false security that this type of prop provides can be worse than no prop at all, since it invites complacency.

Bottom line: We won’t use these, and we’ve removed a few. If you have these on your boat, especially on a cockpit locker, we recommend changing them to something safer.

FRICTION STRUTS

Found on many deck hatches, friction struts have a means of adding friction at the hinge, or to a metal prop. These can be reliable if maintained, but they can be prone to slamming if you allow them to become loose. It is tempting to leave them loose, because opening the hatch is easier—but this could cause it to slam down unexpectedly. It is better to find the right amount of friction required to hold the lid open, yet still allow you to raise or lower the hatch.

Bottom line: Friction devices, especially when overtightened, can put more strain on the fastening hardware, so any screws should be firmly bedded and backed in the hatch and frame. Repeated use of friction props on wood frame hatches can split the wood.

GAS STRUTS

Like the gas springs found on your old hatchback car, don’t expect the gas struts in your hatches to last more than 3-5 years in the marine environment. Replace them as soon as they start slipping.

Bottom line: Most gas struts are not truly marine-grade, so grease the pivots and rods annually to keep corrosion at bay and monitor for signs of imminent failure.

PROPS

Any props used to hold hatches up must be secured on both ends, like the prop on your car hood. The props used to hold up the lids to the lockers under the berth on our PDQ catamaran seemed precarious, but never failed. The props were lightly lodged against the cabin bulkhead carpet, but there was enough pressure with the mattress on top of the lid that the props never slipped. Several times I knocked the prop with my hand or head and it never moved. The lid to the locker concealing the head on my F-24 is held open by a prop that is secure in both the open and closed positions by Velcro pads.

Bottom line: Props are a simple solution, but not infallible. A capable do-it-yourselfer can usually come up with an arrangement that keeps them safely in place while in use, but if you are entering a locker that is propped open, be sure that it can’t accidentally be knocked out of place.

BUNGEES

Bungee cords are commonly used as a safety line to keep hatches open. You can use a hook to attach bungee cords to the hatch, but it’s often faster and more convenient for the bungee to wrap over the lid. We use the latter method on the F-24’s anchor locker, as well as the toilet seat. Bulk shock cord from New England Ropes and Sailrite, and pre-made bungees from Davis (Mini-shockles), and Grainger (EPDM heavy duty rubber) performed well in our evaluation. Pre-made bungees from big box retailers are hit or miss—avoid the cheap multi-bungee cord packages (see “Shock Cord Test Looks at Long Life,” PS March 2022).

The nice thing about bungee cords is they are effectively self-stowing, snapping out of the way when they are not in use. You will want to add chafe protection if you are wrapping them around sharp edges, or if they will be exposed to UV. Chafe protection is easy to fashion out of tubular nylon webbing.

Positive attachment to the locker lid and to the lifeline, stanchion, or other hardware that secures the other end of the bungee is important. The standard bungee hook is not a good choice for this task, since it can bend or accidentally unhook.

We splice the bungee to a padeye on the lid and replace the standard bungee hook with a carabiner that has a latch. The latch ensures that there will be no chance of the bungee letting go at either end.

Bottom line: Simple and cheap, a bungee cord with chafe protection is a fine solution for locker lids.

RETENTION CORDS

A cord with a loop that fits over a winch or hook provides a secure and easy way to secure a hatch lid. Double braided 3⁄16-inch nylon is more expensive than cheap poly cord, but it is well protected against UV and chafe. Dyneema cord is also easy to work with.

Bottom line: As with bungee cords, be sure that the line is well attached at both ends.

LATCHING DEVICES

Some people insist on latching lockers for security against theft. Maybe we’re just lucky, but in our home marina, we’ve never felt a need to lock the boat. In fact, we prefer to leave our boat unlocked in case the bilge alarm goes off and one of our neighbors is nearby (another good reason to meet your neighbors!).

Other latches are essential to the boat’s integrity. Bow anchor lockers, like any locker that is not well sealed, can scoop up a lot of water fast. If a cockpit locker connects with the main cabin (as is the case with many daysailers), the locker is, in effect, another companionway. And like the companionway, if the locker is breached, serious flooding can result.

Companionway boards aren’t much help if they are blown overboard in a storm. That is why racing regulations require that companionway hatch boards be secured against falling out when the boat is inverted. They also need to be secured when they are not in place.

DRAW LATCHES

Draw latches are among the most common type we see on boats. Often seen on high-priced ice chests, they use leverage to put tension on a hook. The rubber type of draw latch is rugged and well proven for securing engine hoods and battery case covers on heavy duty trucks. They tolerate misalignment and movement better than metal versions.

Instead of the handles with a big T-handle that sticks up, we’ve used the flat, low-profile style. The only downside is that the UV eventually eats away the rubber, and the latch will need to be replaced every 8-10 years in mid-latitude sun. They will also expand in tropical temperatures, although seldom to a point where they don’t securely latch. Fortunately, the handles are inexpensive, easy to replace, and very reliable. You can buy them in a pack of four or more for better pricing and to have some spares.

Bottom line: Draw latches are an economical solution for many latching needs because they tension the lid and are good for gasketed lockers. For durability, metal is better, but achieving the right tension requires more careful fitting.

BARREL BOLTS

Unless it is always under tension, a simple barrel bolt latch can rattle open. If gravity is the only thing that keeps the handle down and locked, what will keep it locked in a knockdown?

Bottom line: Use barrel bolts with caution. Look for styles with a snug fit.

RETENTION CORDS

A retention cord, often used in combination with a small cleat can be a simple solution to your latching needs. A retention cord can be used for securing hatch boards, for example. The line can be attached to each board through a pad eye or similar eye. In this way, they are also secure against going overboard. A retention cord is also useful for securing cockpit lockers. A retention cord with a corresponding cleat (or a pair) can also be used to lock hatches from inside the cabin. Over time the cords can chafe, so inspect regularly.

Bottom line: Although they are not as quick to use as a simple latch, a cord with a cleat has long provided a positive means for securing hatches. Adding one to your hatch boards before heading offshore will give you peace of mind.

CONCLUSION

Unfortunately, many boat makers don’t put as much thought into the latching mechanisms as they should. Older boats in particular are likely to have latches that are broken or worn to a point that they no longer provide security. Systems used to hold locker lids open should be foolproof. This is particularly important for lazarette lockers, which often provide the only entry and exit to the engine room or quadrant under the cockpit (see “Safety Procedures for Confined Spaces”). If a hatch has the potential to hurt someone or cause a loss by opening or closing when it shouldn’t, secure it. Include, an inspection of all hatches before heading offshore.

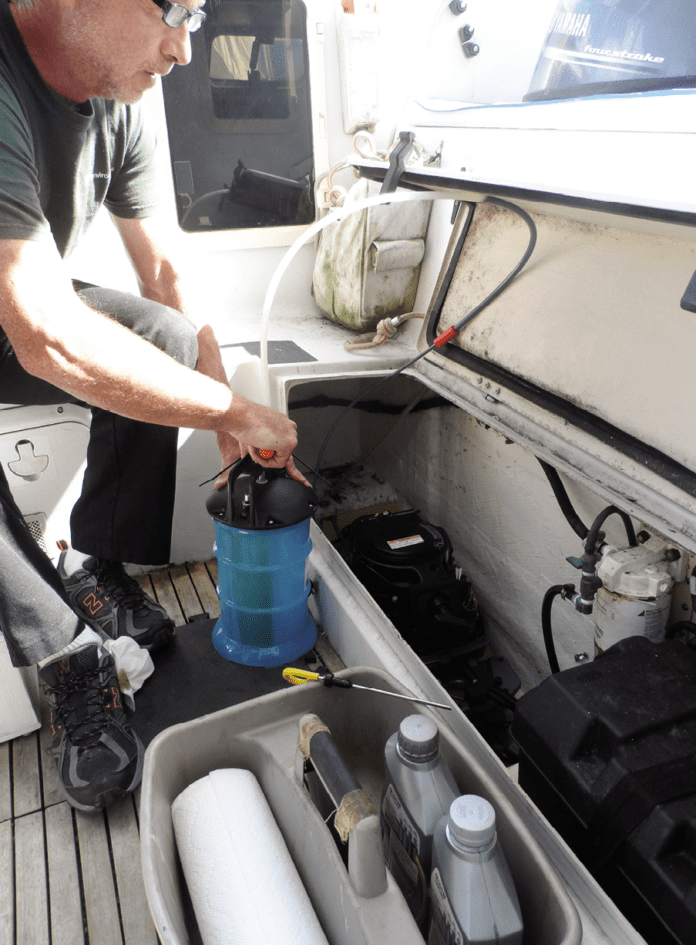

1. A piano hinge on this locker allows it to open more than 180-degrees and stay open with out a prop.

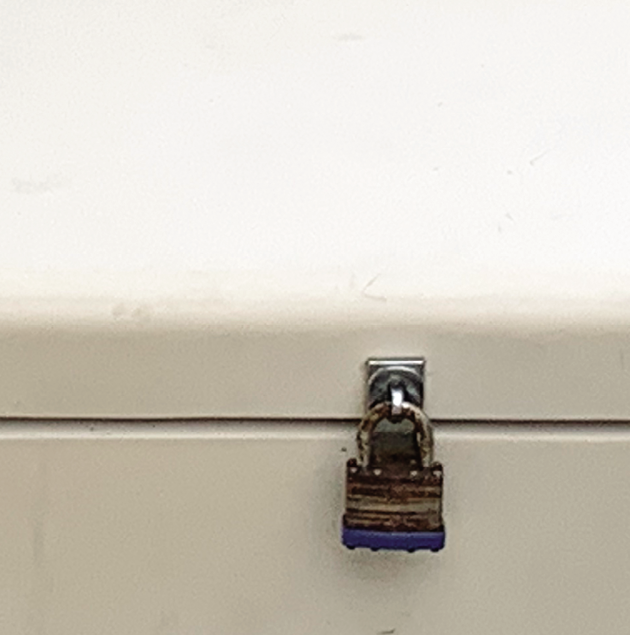

2. A locking hasp can prevent theft, but it won’t be enough to keep the locker completely watertight.

3. The twist-lock latch on this poorly-latched anchor locker relies on just two small screws to keep heavy ground tackle in place.

4. The barrel lock on this Hunter keeps the lid down, but there is so much play that the locker will never be dry in a seaway.

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS

1. The companionway to this Contessa 26 has been upgraded by the owner. The hinged top panel can be flopped open, the lower panel is more than two feet off the cockpit sole.

2. This latchless cockpit locker lid on this old daysailer opens

directly to the main cabin. In this case, it appears the owner removed the latch to paint the lid.

3. Stress cracks around this hatch hinge should prompt closer inspection for signs of rot or structural weakness.

4. With proper care, cleaning, and lubrication, this silicon bronze lift-and-turn hatch locker latch will last as long as the boat.

5. This neatly installed silicon bronze hardware and lock will deter thieves. Vents cut into the top hatchboard will be a vulnerability offshore.

1. A hinged dowel keeps this stern cabin hatch firmly jammed open.

2. You can make a bungee cover out of tubular webbing or the cover from double-braid rope.

3. After trying several different types of latches to keep our cockpit lockers secure, we now rely on low-profile draw latches.

4. Friction screws on hatch hinges need to be kept clean and free of corrosion to work properly .