A Practical Sailor reader recently reached out to me with a question regarding light air sails on catamarans: “I’ve owned two catamarans, and have wondered about flying spinnakers. The common thread is that the main must be flown because the main sail/sheet acts as a backstay . . . I have always found it difficult to have the main and spin up at the same unless running about 150 degrees or more off the wind.”

Mainsheet tension on cats is primarily important when beating to windward. Lacking a backstay, much of the forestay tension comes from the mainsheet. When the mainsheet is slack or the mainsail furled, the genoa becomes full and baggy, and both heeling force and leeway increase.

A tight mainsheet, on the other hand, keeps the forestay tight and straight and the jib shape is as designed. Thus, it is better to have the main up anytime the apparent wind is forward of the beam, even if deeply reefed.

Another reason to have the main up is for balance. With only the genoa up, the boat will develop considerable lee helm, constantly trying to turn away from the wind. This is fine if the apparent wind is aft of the beam, but with the wind farther forward, you will find that you can’t beat, tack, and perhaps not even to turn into the wind, because the wind and waves will overpower the rudders. Poor balance is also hard on the autopilot.

Another reason to fly at least some mainsail is furling. Without a mainsail to block the wind, it is hard on equipment and can be just plain impossible in a blow. I often watch folks struggling to put the genoa away to windward, often resorting to a winch and courting serious furler damage. Most likely they could have furled the sail by hand in even a fierce wind, if they had only turned downwind (apparent wind about 150 degrees off the bow), hiding the sail behind the main. It is also much easier to drop the chute when it is blanketed by the main.

The mainsail is eased well out when reaching and does not add vital support when flying a spinnaker in moderate conditions. It does help stabilize the mast in strong conditions, but hopefully you will have the chute down by then. Looking aloft, the angle of spinnaker force is given by the direction of the halyard. In general, it is well to the side and is carried efficiently by the cap shrouds.

The Fast Cat Factor

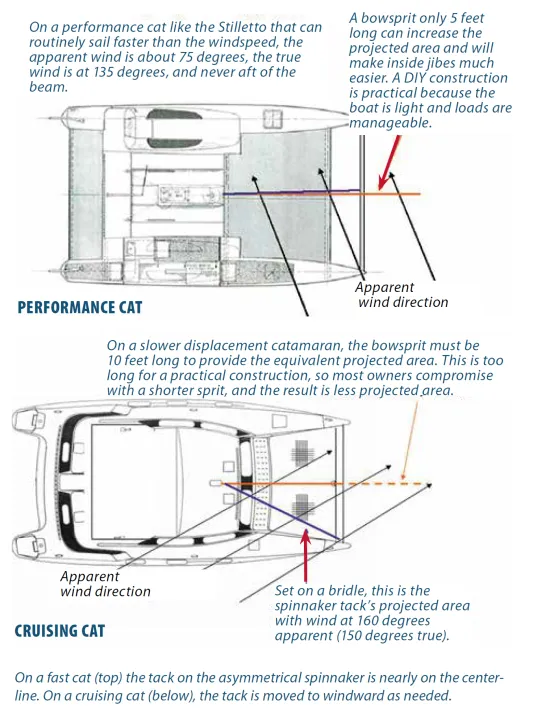

Multihulls don’t fly chutes deep downwind. They reach. But there are shades of meaning in that and some half truths spread about cruising cats. Four decades ago I mounted a long sprit on my beach cat, and she went like mad. My next boat, a Stiletto catamaran, A Kevlar honeycomb speedster, carried a chute on a sprit.

Both of these boats routinely exceed windspeed when sailing off the wind, and we never carried the apparent wind farther aft than 75 degrees off the bow. A good downwind jibe was actually a tack, with the spinnaker blowing aft, like a jib.

The Cruising Chute

My next boat was a PDQ 32 cruising cat. While a good bit faster than a monohull of the same length, it had barely half the maximum speed potential of my earlier racing boats, never sustaining more than 12 knots. Coincidentally, the fastest VMG (velocity made good to leeward) course for both boats was about 130-150 degrees off the true wind. But the best apparent wind was much farther aft, as much as 150 degrees off the bow.

With the apparent wind that far aft, the best way to fly a spinnaker is NOT with a centerline spinnaker pole, as has become all the rage, but rather a bridle that hauls the spinnaker tack to windward. This provides more projected area, helps the chute rotate to windward, and is lighter and faster when going deep.

It also better suits a full chute designed for going downwind, whereas chutes sprits are generally given a much flatter cut, better suited for reaching on hotter (apparent wind forward of the beam) courses. I considered adding a sprit, even gathering some of the materials and running through the engineering, but it would have been slower on my native Chesapeake Bay, which emphasizes windward/leeward sailing in our typical summer weather patterns.

Yes, with the main up will have to jibe downwind, but will be about 30 percent faster VMG than just flying a chute alone, depending on the wind conditions. And, by keeping the main up, you can easily switch to a higher course if the wind changes, easily strike the chute in a blow, and change to main and jib when it becomes too strong for the chute. The winds are light and you don’t you want the extra speed? That’s up to you, but I didn’t buy a cat to go slow.