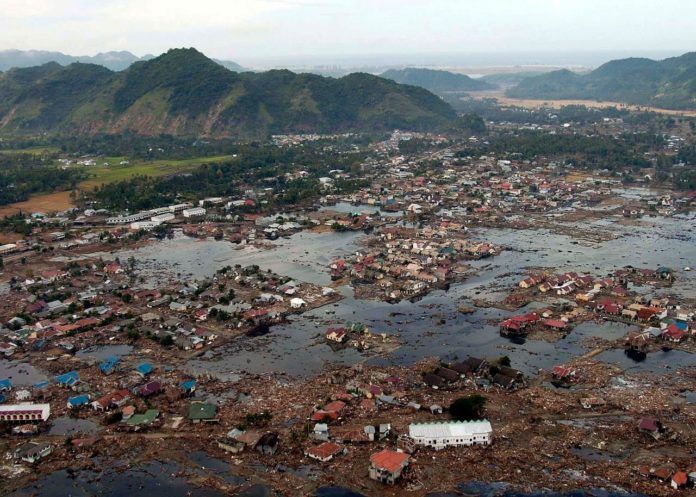

The earthquake that struck Indonesia, one of my favorite cruising grounds, earlier this year had me thinking again about the risk that few cruisers—including myself—never really considered when we set out. It’s not the sort of thing you want to be too pre-occupied with, but if you intend to spend a lot of time in the Pacific Rim, or other areas that experience frequent earthquakes, it is good to have a plan.

Twice in the Pacific we found ourself under a tsunami watch, and realized how little we actually knew about tsunamis and the warning systems in place to reduce casualties. Since then, several destructive tsunamis have resulted in much better monitoring and prediction systems. One of the more helpful resources for understanding the warning systems can be found at NOAA’s Pacific Tsunami Warning Center. Another good resource is the User’s Guide to Tsunami Warning Products for American Samoa. All cruisers who frequent tsunami prone areas should be familiar with the types of tsunami warning statements issued by public agencies — information statement, watch, advisory, and warning. They should also take a few basic precautions so that they are prepared should a tsunami threat become real.

PS Contributors John Neal of Mahina Expeditions bluewater voyaging school has weathered a few earthquakes and tsunamis in his decades of teaching others aboard a variety of cruising boats, including the familiar Hallberg-Rassy 46, Mahina Tiare III. (Recently sold, Neal’s HR 46 is now moving on to new adventures.) In the wake of the 2009 tsunami on Samoa, they devised an earthquake/tsunami awareness and response system. This and other topics are part of the Mahina Expeditions curriculum.

The first step to survival is preparation, and we hope sharing Neal’s insights and firsthand experience will help others cruising tsunami-prone waters to be better prepared in the event of an earthquake.

From Mahina Expeditions:

As sailors, we need to be aware of the ever present threat of a tsunami. By establishing emergency procedures for your crew and vessel along with knowing what to expect and what to do in the event of a tsunami, it will be far less likely that you or your crew will become casualties or that your vessel will sustain damage. Worldwide, 59 percent of tsunamis occur in the Pacific with 80 percent being the result of earthquakes.

In the event of an earthquake, time is of the essence as there may only be four minutes from the time of the earthquake to the arrival of a tsunami. Tsunamis travel at 300 to 600 mph in the deep, open ocean, so waiting to see if civil defense alarms sound after an earthquake is not wise.

When we experienced the earthquake in Apia, Samoa, in 2009, the alarm sounded approximately 12 minutes later. Already, the water had been rapidly receding from Apia Marina where we were moored. At the instant the sirens went off, the tsunami was already coming ashore on the south side of the island in a series of waves that would claim over 130 lives. The quake was centered approximately 120 miles south of Samoa and about 100 miles west of American Samoa.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Pacific Tsunami Warning Center is located at Ewa Beach, Hawaii. They have seafloor and coastal sensors located around the Pacific, but after an earthquake, it takes them at least 12-15 minutes to analyze data to determine whether there is the potential for a tsunami. It is important to note that there can be as many as 300 to 400 miles between tsunami crests; therefore, after the initial tsunami wave hits, the second wave or series of waves may occur up to one hour later. This was the case in the 1960 tsunami that devastated Hilo, Hawaii, claiming 61 lives.

Mid Ocean

Because a mid-ocean tsunamis wave height is generally less than 3 feet, tsunamis are frequently unnoticed by mariners sailing those waters.

When Ashore in a Coastal Location

In any coastal location, always note the tidal range and times. If you ever see the sea level receding lower than normal, realize that this is the natural warning sign of an approaching tsunami. If ashore, do not go out on the exposed reef or shore to collect fish, as locals frequently do. Immediately run inland to high ground or get above the third floor of a sturdy building, if available. Tsunamis have traveled .7 miles and can go further inland if the terrain is flat, so the option of going to the highest floor of as sturdy building may be safer than attempting to just run inland.

In the Samoan tsunami, the ground floors of many buildings were washed clean of everything, and it would not have been possible to survive due to backwash of debris and swift currents, while above the third floor, many buildings were relatively undamaged.

When Aboard

If you are docked and experience an earthquake or rapidly receding water, immediately start your engine, cut your docklines and motor at full speed to water deeper than 150 feet. If the event occurs at night and/or it isn’t possible to safely leave the harbor, quickly leave your boat and run for the hills or to a tall, substantial building.

At Anchor

If you are at anchor and experience an earthquake or rapidly receding water, immediately start your engine, raise your anchor and get to deeper water. In the 2009 tsunami that hit Niuatoputapu, friends aboard a 39-foot sloop tried to raise anchor immediately after the earthquake but found their chain wrapped around a coral head, so they let out all of their chain. When they saw the 13-foot high surge come over the reef they kept the bow pointing into the wave while maintaining full forward throttle. They managed to survive the series of waves and swirling current with only stretched chain and a damaged windlass.

When leaving the boat

Here are some priorities to quickly grab:

1. Passports, cash and credit cards

2. Iridium satellite phone

3. Cell phone

4. VHF handheld radio (this proved very helpful in Samoa)

5. Flashlights

6. Knapsack

7. Water bottle

8. Granola bars or similar foods

9. Necessary prescription medicines

10. Running shoes

11. Jacket