With our Southwest Florida office so near to the path of Hurricane Ian’s eye, we’re getting a sad, up-close look at the storm’s impact on local boats and coastal infrastructure. We’re also gaining a better understanding of what sailors and the ports that serve them can do to minimize their risks in future storms. Since it is still so soon after the storm, there is still plenty to be learned. Three immediate observations stood out to me.

Hurricane Junction

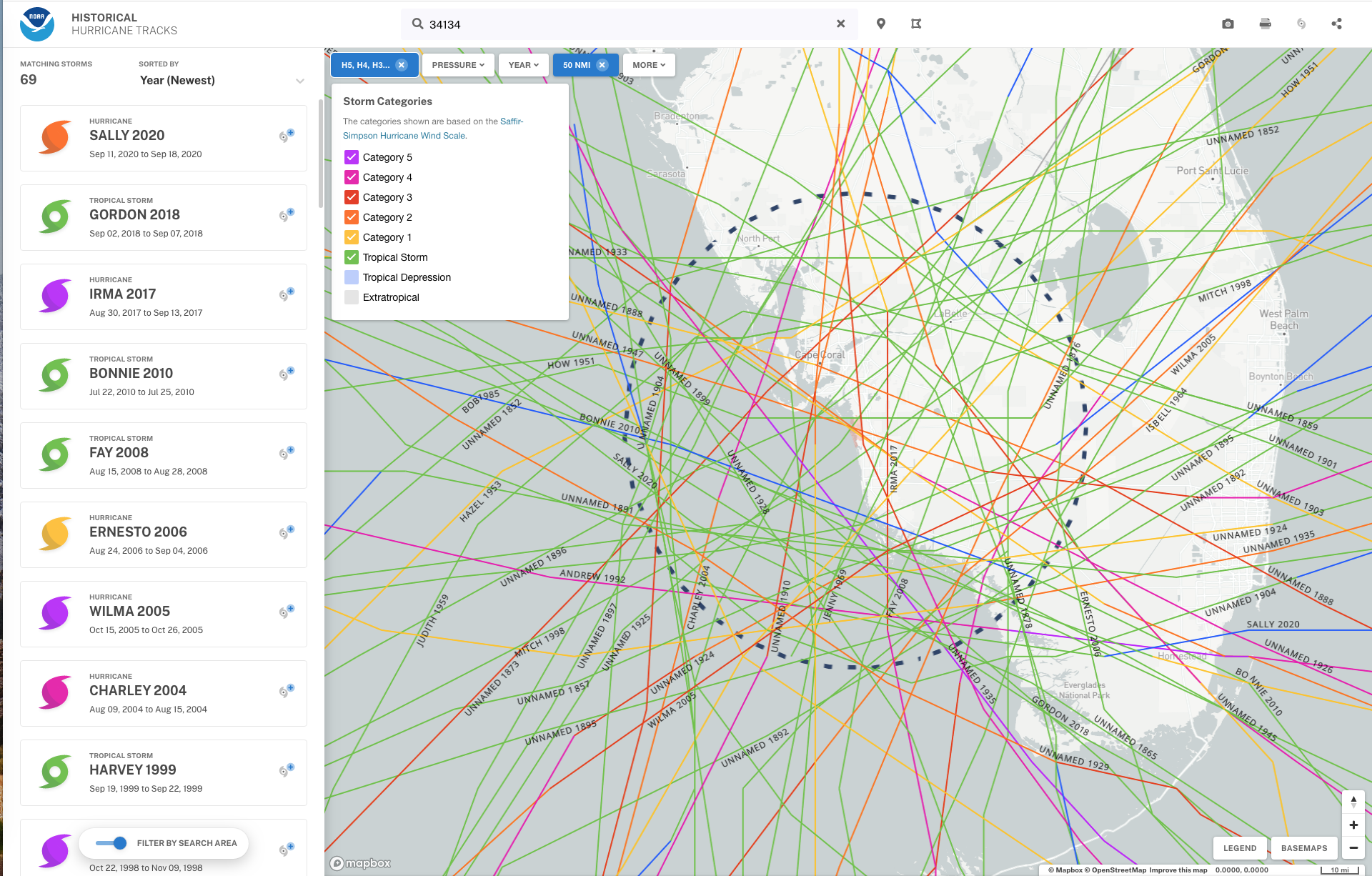

Southwest Florida is a risky place to keep a boat during hurricane season. Even very early in the storm’s development near the island of Grenada, the risk to Florida’s Gulf Coast was clear. Storms moving east at that latitude frequently enter the Gulf of Mexico and intensify, posing a threat to the southwest corner of the Florida peninsula, an area that is also vulnerable to storms approaching from the Atlantic. As the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s historical hurricane tracks data show, a total of 69 recorded storms have impacted areas within 50 miles of the small dimple in the southwest Florida coast near Bonita Springs, just south of Sanibel Island and Ft. Myers. The area around Marco Island, just to the south, has been criss-crossed by dozens of powerful storms so frequently from so many different direction that the NOAA historical map resembles that for flight paths into Atlanta’s Hartsfield Airport.

The second predictable impact was flooding. The shallow cruising area between Charlotte Harbor and Everglades City, the Gulf Coast gateway to the Everglades National Park, is swamp—a wild and beautiful mangrove and sawgrass estuary where the Florida peninsula, tilted slightly southwest, spills Everglades freshwater into the bay. Originally, much of the land remained underwater year round, and the mangrove forests served as a critical barrier to erosion from wave action while providing a nursery for marine life. Mammoth tracts of this swamp has been filled and paved during the last century. But dredging and filling the swamp-bottom doesn’t stop the water from coming.

Try as we might, draining this region is like bailing your bathtub with both faucets running full gush. Just when you think you’re making progress, along comes an Ian (2022), a Sally (2020), an Irma (2017), a Wilma (2005) or a Charley (2004) to drain their salty Gulf swimming pool into your tub. Dress code for Florida hurricane season should include a rubber ducky and snorkel.

Predicting Landfall

Pinpointing landfall in this region is a fool’s errand, especially storms such as Ian with wide wind fields and expansive rain bands. Despite great strides in weather prediction the “cone of uncertainty”—the cone-shaped area predicting the path of the eye—remains broad. And impacts can be felt far beyond the storm’s center. This means areas outside the cone are not invulnerable, and if you are anywhere near the cone, you need to make preparations.

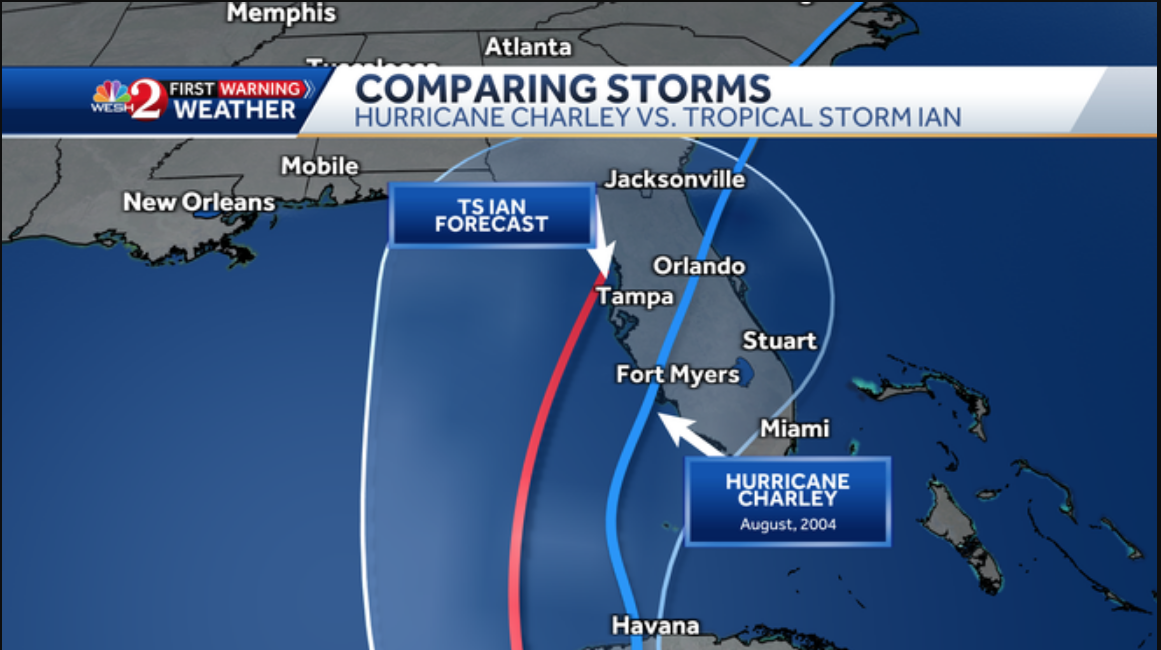

It matters what model you follow. Days before the storm, Ian was predicted to follow a more northward track, based on weather modeling by the U.S. Centers for Environmental Prediction using the Global Forecast System (GFS). But even if it had, the Marco Island area would likely have felt at least some impacts, including dangerous storm surge and torrential rains that could lead to potential flash floods.

Ultimately, the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasting, the so-called “Euro model,” proved more accurate with Ian. As the storm approached and then crossed the island of Cuba, the Euro model consistently showed a more eastward track, closer to the one that Ian ultimately followed.

Preparation matters

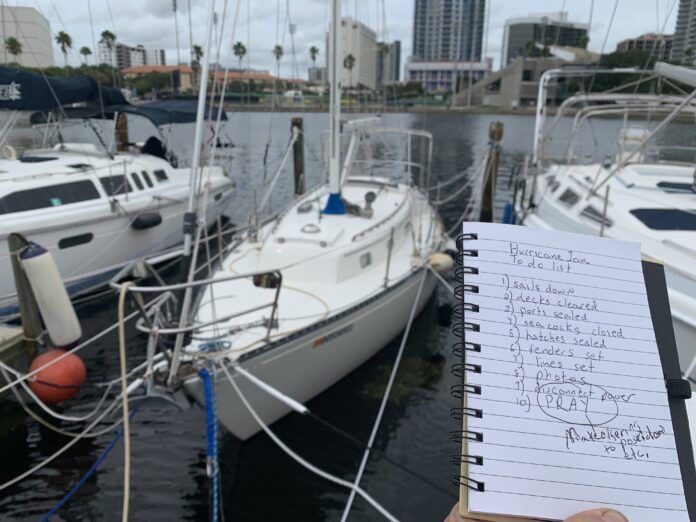

Finally, preparation does matter. Even in marinas hardest hit by Ian, there were boats that survived without significant damage. Granted, there was a fair bit of luck involved. The biggest variable is the preparation of nearby boats. You can engineer dock lines, fenders, anchors, or moorings that will greatly minimize the risk of damage from wind and sea, but as soon as other boats begin careening down on you, those efforts are overwhelmed. Even boats that were hauled out and strapped down as many insurers require came to grief in the storm.

In my fixed-pier marina in St. Petersburg, the biggest risk was the extreme low tide. Many owners secured their boats with the expectation of a high tidal surge, since that is what experts were warning about the day before the storm made landfall. However, since the marina was on the north side of Ian’s eye as it made landfall, the strong north winds pushed water out of Tampa Bay.

Several boats lost cleats or were damaged as the tide sharply fell and then rose again, trapping them under the docks. Most boatowners, however, having gone through several prior storms, were aware of this risk and planned accordingly. A nearby marina with floating docks and tall reinforced concrete pilings fitted with sliding harnesses for docklines did not suffer this same problem.

For more on preparing your boat for survival storms in port—everything from Atlantic tropical storms to Mediterranean mistrals—our Hurricane Preparedness Guide covers the minutia of securing your boat at a storm mooring, in a hurricane hole, or at marina.

You’ve made the same mistake that many folks do: the Forecast Cone is a prediction of future positions of the eye of a storm. It is not the area likely to be impacted by the storm. If the eye follows a path close to the edge of the cone, the area “impacted” will extend well beyond the cone.

To quote an article by Scott Dance and Amudalat Ajasa from the Washington Post on October 4th:

“Its image is ubiquitous ahead of any hurricane, fundamental to decisions coastal residents, first responders and politicians make to prepare for storms and to evacuate: the forecast cone.

But amid finger-pointing over what mistakes may have contributed to dozens of deaths during Hurricane Ian, the concept of the cone is being questioned.

The National Hurricane Center graphic is perhaps misunderstood as widely as it is broadcast. It simply shows the likely future locations of a storm’s center — that is, the path weather-forecasting models suggest its eye will take over the next three to five days.

But many view the cone as indicating that danger is limited to areas within a shaded wedge of the map. “Some people think the cone represents the size of the storm, which it doesn’t,” said Rebecca Morss, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. “Some people think it represents the area of impact, which it doesn’t.””

This misunderstanding leads many people to make the wrong decisions in preparing for a storm.

I was about to comment with exactly what Don wrote above. The only thing I would add is the concept of the “Dangerous” and “Navigable” semicircles which are, I believe, discussed in Bowditch. The effect of being in the Dangerous Semicircle is vastly magnified by the shallow water and low land where Ian struck. It is tragic that the emergency management people as well as the public seemed to minimize or ignore this reality.

Excellent explanation, Don!

Yes, it’s a great article (link below), and just one of several the Washington Post has published over the years trying to help us better understand the models. One thing we natives have learned over the years living in Florida is that hurricanes can slow down, stop, turn, zig zag, even make circles, and relying on the nice little line of the forecast track of the eye is potentially dangerous.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2022/10/04/hurricane-cone-map-confusion/

All boats of significant value should have been taken to a safe harbor well removed from the path of Ian such as New Orleans. I have no sympathy for owners who did not properly protect their investment. I own a 55′ heavy displacement motor sailer that would have been removed from harms way well ahead of the storm. I trust the insurance companies mandate this action because now everyone will be paying higher insurance premiums due to the high loss from this storm. My boat is in CT now and is not allowed back in FL until after November 1st per my policy and must be out of FL by June 1st.

Hurricanes are highly unpredictable, so trying to forecast what they do is nothing more than a crap shoot. I totally agree about moving a boat out of Florida during hurricane season. I live here and have been through four hurricanes on the east coast. These beasts are about as predictable as a rattlesnake with a bad attitude. Most of Florida has one way in and one way out. You can only go so far east or west. But, people will continue to pour into Florida, builders will rebuild on the sand, and folks will return to their lives. This is a massive wake-up call that shows how weak the infrastructure really is. High water table, low elevation, landfill, poor drainage in many areas, and the coasts are overcrowded.

All true. Hide somewhere else.

But we did already know all of this BEFORE Ian.