With all the rain this spring, boaters in almost every region of the U.S. are dealing with mildew on their boat. For many of us mildew is a year-round problem, but it can be especially acute in spring and fall. Many boaters combat mildew on their boat the same way they deal with it at home—they buy some bottled spray (usually with some form of bleach in it) and spray away, hoping for the best. Not only are the chemicals in these concoctions toxic in the marine environment, but this approach does not deal with the root problem, and until this is addressed, mildew will inevitably come back. What’s worse, the chemicals that are in that bottle can harm the fibers and fabrics, taking years off the life of our expensive sails, canvas, and cushion covers.

Mildew breeds in humid conditions—any space where humidity is much above 50 percent can become a microbe farm—and one of the easiest ways to control humindity is through temperature regulation. To maximize your ability to regulate temperature without racking up a big electric bill, you first want to look at your insulation. Insulation is a great energy-saving expedient; if our heater or air conditioner is undersized, fixing drafts, shading or insulating windows, and insulating non-cored laminate are all ways to reduce the thermal load. For boaters, however, that is only half of the equation.

Mildew problems vary by location. In Florida, air conditioning ducts can fill with condensate and breed a horrible mildew soup. In Maryland, a cold drip from a window can ruin a deep winters slumber. If the Pacific Northwest were a planet named by boaters, it would be Planet Mildew. In Winter Sailing Tips for Die-Hards, we touched on insulating windows, plugging drafts, and humidity control. In Dirt Cheap Insulation for Liveaboards, we compare various insulating materials and their effectiveness in reducing humidity by keeping boats (or any interior space, for that matter) dry and comfortable.

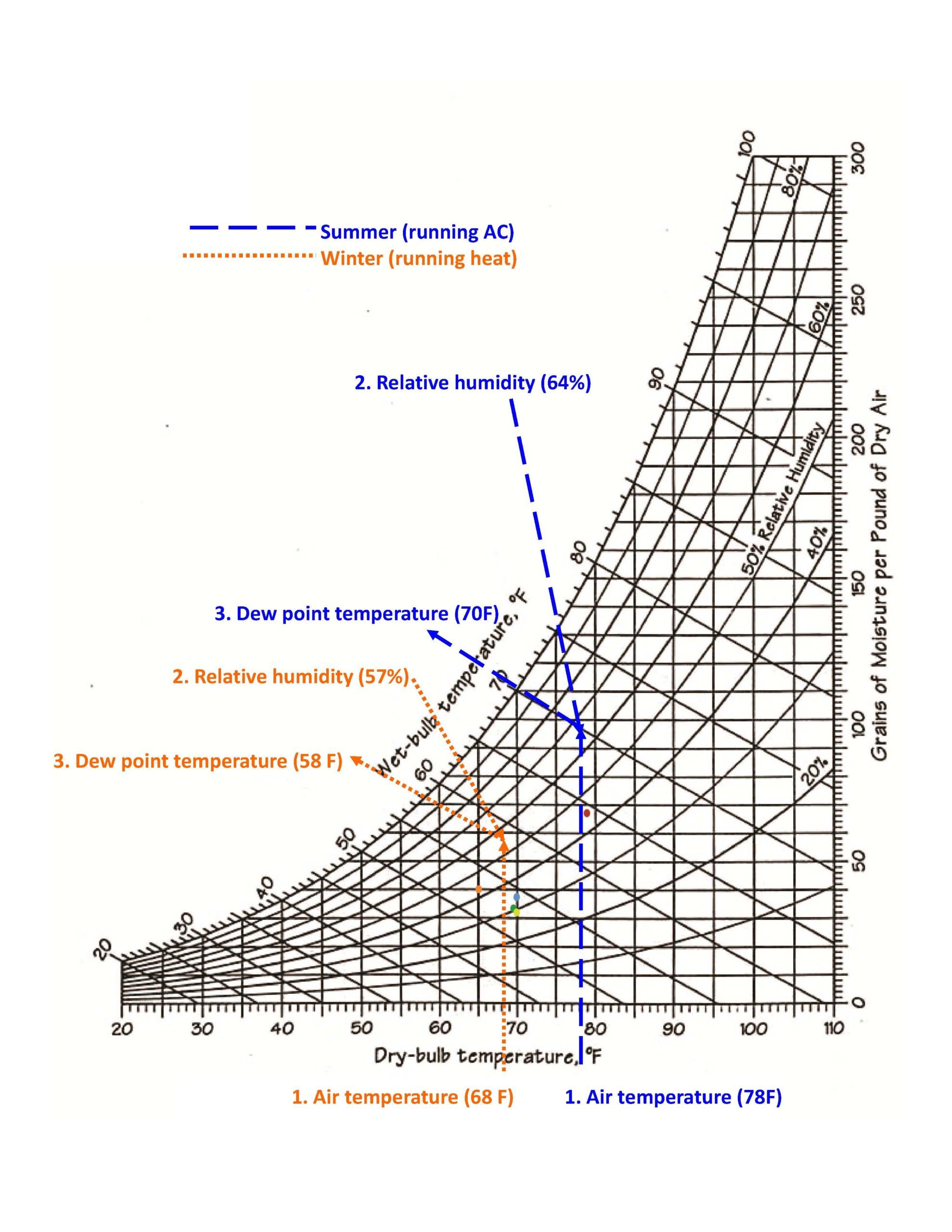

Whether a surface sweats—a cold window in the winter or AC ducts in the summer— depends on if the surface is below the dew point. If you Google dew point in your location (or one nearby), you can get a general picture of the dew point is in your area. There are also a number of smart-phone apps that you can use to determine dew point. Because even a small boat can have some micro-climates where moisture and temperatures vary from the norm (the bilge is a great example of this), truly effective mildew prevention depends on understanding the relationship between temperature humidity. (The existence of these micro-climates is one of the main reasons we empahasize on board ventilation.) If you can regulate boat temperature to control the dew point in moisture-prone areas like your bilge or head, chances are, you will have mildew licked everywhere on your boat. One of the easiest ways to visualize the relationship between temperature and humidity is with a psychrometric chart.

The adjacent psychrometric chart illustrates the worst case winter condition (68 F in the cabin, 55 percent relative humidity, 57 F dewpoint) and summer condition (78 F in the cabin, 64 percent relative humidity, 70 F dew point) on the test boat. In theory, any surface below the dew point will sweat, and this was very close to our experience; any surface that was below the dew point for significant time periods got wet and mildew bloomed. Note that we are discussing surface temperature, which is not the same as air temperature. (The $32 Klein IR1 is a handy tool for gauging surface temperature.) By getting a clearer picture of the relationship between the surface temperature and humidity, we were able to correct these problems with a combination of insulation and controlled ventilation.

Drew Frye

Insulation must be sealed. If the outside or duct temperature is below the dew point, there will always be a location within the material that is at the dew point. Moisture will be drawn to that area. There are only two ways to avoid condensation within the insulation. In the case of fiberglass insulated AC ducts, the insulation has an air-tight jacket, and the jacket is sealed with duct tape and captured under clamps at each cut end. Alternatively, a non-absorptive insulation such as closed cell foam can be used, but it must be tightly bonded-not just taped-to the surface so that air cannot get under it.

Perhaps the most common failure to understand this is demonstrated by mildewed, vinyl-covered foam ceiling liners. Installed over a non-cored hull, these are virtually guaranteed to sweat, even if deck fitting leaks don’t get them first. All of the benefits of insulation can be overwhelmed by the downside of mildew growth unless insulation is very carefully installed.

Curiously, the best way to prevent condensation in uninsulated spaces during winter is to let them go cold and restrict ventilation. The more warm dry air you pump into them in an effort to dry them, the more water you have made available to condense. Instead, only ventilate these spaces on the coldest, driest of days, when you can leave the boat (people add moisture) and let the heater and dehumidifier do their work. We have areas in the test boat that are well below the dew point (bilges), but they stay dry so long as we don’t try to air them out.

If you are already dealing with a mold or mildew problem, whether it’s in your interior spaces, on exterior surfaces, or in your sails and canvas (clear plastic is especially mildew-prone), our comprehensive e-book The Mildew-free Boat, offers tips on cleaning mold and mildew stains and preventing them from coming back.

And if you are curious about our research into breakthrough products and techniques to keep your boat clean without cutting into sailing time, check out our three-volume Marine Cleaning Guide. This covers everything from gel coat restoration and protection, to essential cleaners and protectants, to specialty cleaners formulated to deal with specific problems.

To download a PDF version of Practical Sailor‘s psychrometric chart, click here.

So if we had a dehumidifier on board that kept the interior at about 45% humidity, we should be good to go. We purchased a new to us boat and there is a few areas with slight surface mildew. We are in NC and it never gets really cold, but a good dehumidifier kept any additional growth in check. Of course once we are away fro shore power, the advice noted in the article(s) will be very helpful. Thanks.

RE: “Curiously, the best way to prevent condensation in uninsulated spaces during winter is to let them go cold and restrict ventilation.”

So, in leaving my boat at its Northwest location buoy 24/7/365, I should close the hatches and plug the dorads to restrict air flow. Correct?

Michael: We could have been more clear in stating that we were speaking of occupied boats. Farther down the same paragraph we said “Instead, only ventilate these spaces on the coldest, driest of days, when you can leave the boat (people add moisture) and let the heater and dehumidifier do their work.”

If a boat is out of the water and unoccupied, full ventilation makes the most sense. The air inside and outside will be roughly the same temperature and condensation should be minimal. The bilge should be dry. If the boat is in the water it is trickier. In the spring the water can be much colder than the air, and no amount of warm, humid air is going to dry the bilge when the water is below the dew point. You can’t dry a glass of ice water by leaving it out on the counter. You can keep the glass dry by running a dehumidifier and drying the air. A glass of ice water does not sweat in cold climates in the winter or in the desert in general, because in both cases the air is very dry.

The reverse problem can happen in the fall, when the water is warm and the cabin gets cold. It can feel like a green house, with water running down the walls, unless the cabin is very well ventilated or the bilge is dry. In this case, the cabin walls are below the dew point of the air moving up from the relatively warmer bilges.

How do you run a dehumidifier if you are on a mooring? It’s a challenge. That said, on my last boat I ran an Evadry 2000 on a timer off my solar power system without ever plugging in. A small dehumidierfier does not use much power and if the boat is closed up, there should not be much moisture to remove (fix the leaks). I ran the dehumidifier only at night, because they are more efficient when the air temperature is lower.

Ventilation alone can prevent condensation in many boats, most of the time. But if the temperature of the air and water are very different, a dehumidifier will work better. Dry the air to below the dew point of which ever is colder.