The fastest way to attach light hardware to a cored deck is a self-tapping screw. It is also the fastest way to have hardware rip out of the deck and end up with a wet core and delaminated deck. But how to replace screws that have gotten loose or prevent a wet deck in your future? One method is to drill and over-sized hole, remove some core, fill the enlarged hole with epoxy, and then replace them with small through bolts (see Spreading the Load Practical Sailor, August 2016). But what if the backside is inaccessible? Can we create an improved repair by filling and reinstalling a self-tapping fastener, without major surgery? What sealing and filling material is best?

Photos by Drew Frye

What We Tested

Neat epoxy, epoxy thickened with sawdust, micro-balloons, colloidal silica were used to fill test holes. We also stuffed fiberglass cloth into holes and tested solid materials for comparison. We used #8 sheet metal screws and drilled and plugged the same -inch cored deck samples fabricated for prior PS testing of backing plates and washers. The panel consists of a 1/2-inch balsa core with skins hand laid from three-layers of 17-ounce triaxial fiberglass cloth, using West Systems epoxy.

How We Tested

We drilled 7/16-inch holes through the top skin and core only. We then inserted a modified roofing nail cutter that removed the core and additional 5/32-inch of core from under the skin.

Holes were then filled with West Systems Epoxy using slow hardener. Additional holes were filled with the same epoxy thickened with either sawdust, West Systems micro-balloons, or Cabot M-5 colloidal silica (also called cabosil, or fumed silica). One set was filled with epoxy after which it was stuffed full of 6-ounce fiberglass cloth. Screws were fastened while the material was curing, establishing an adhesive bond as well as a mechanical bond.

Additionally, screws were also set in the skin-only, a pine board, and solid fiberglass sheet for comparison. In all cases, a pilot hole matching the core diameter of the screw was used.

Observations

Use slow epoxy systems. The plug is large enough for West Systems Fast Hardener (205) and all 5-minute epoxies to build heat and make bubbles (exotherm). This results in a weak plug.

Fill holes when the temperature is steady or falling. If a cored structure is filled when the temperature is rising, expanding air will come out through the hole, creating bubbles and a weak plug.

It was obvious which systems would be strongest as soon as we drilled the pilot holes. The neat epoxy and epoxy plus fiberglass holes offer some resistance, whereas those using fillers drilled without effort.

The generally poor performance of fillers derives from a variety of factors. In the case of sawdust and micro-ballons, they are fundamentally weak. In principle, epoxy thickened with colloidal silica should be 10-30 percent stronger, stiffer, and harder than straight epoxy. In fact, however, the presence of fillers increases retention of micron-sized air bubbles, originating from the air trapped within the filler itself.

The only way those high-strength promises can be delivered is when the powder and epoxy are blended under full vacuum, eliminating the air, not a possibility for the DIYer. As a result, all epoxy-filler blends are loaded with microscopic air bubbles. These bubbles reduce strength when bonding, and more dramatically when we cut through them in the process of making threads. Pre-blended epoxy putties, such as Marine-Tex and JB Weld are even weaker.

Fiberglass cloth also retains some air, but these bubbles can be worked out with a little gentle prodding, just as you work air out of hand laid fiberglass laminate with a roller. They are not the microbubbles that make thickened epoxy opaque. Fill the hole with epoxy before adding the cloth; this ensures the cloth wetted out and minimizes trapped air.

We were surprised by just how much glass we could cram into an over-sized hole. With just a few moments effort, 15 square inches 6-ounce fiberglass cloth-nearly 1/5 of a sheet of paper-could be crammed into a hole only -inch deep and 5/8-inch in diameter. The glass fibers add both strength and toughness.

Skin-only threads, without an epoxy plug is weak and invites water penetration to the core in exterior repairs. Testing in solid fiberglass reaffirmed a rule of thumb we developed from testing bolts tapped into solid fiberglass; so long as the solid glass is at least two fastener diameters thick, the fastener will fail before stripping. This was also reaffirmed when we witnessed fiberglass-reinforced plugs being pulled right through the skin.

Skin Only

This is asking for a wet core and should only be practiced in dry areas. Strength depends entirely on the original layup and is poor, even for light duty use.

Bottom line: For interior use only.

Plain Epoxy

Straight epoxy is brittle, so it was no surprise when the plug failed by cracking. But it should also be noted that this didnt happen until the load was pretty high, much higher than a fastener this size should be expected to hold. Neat epoxy is easier to work with and easily place in the hole with a syringe. On vertical surfaces masking tape can be used to keep it in place.

Bottom line: Recommended for general use.

Epoxy plus Saw Dust

We thought it might reduce cracking, but it was just weak.

Bottom line: Not recommended.

Epoxy Plus Micro Balloons

Light fillers have real advantages when working on vertical surfaces. They don’t sag. They are also easier to sand when fairing. However, they are weak and don’t hold threads.

Bottom line: Micro-balloons are for fairing, not adding strength.

Epoxy plus Colloidal Silica

Infamous for difficulty in sanding, colloidal silica is used for thickening bonding fillets and where high compressive strength is needed. We were surprised that it didnt hold threads better, until we looked at some samples with a microscope. Although micro-bubbles probably have little effect on macro bonding, they do appear to undermine the structural strength required when re-setting a screw.

Bottom line: Not for cut threads or self-tapping screws.

Epoxy plus Fiberglass Cloth

Fill the hole with neat epoxy. This eliminates the challenge of wetting the glass and getting the epoxy clear to the bottom. Cut a strip about 1-inch wide and 15 inches long, and cram it into the hole using a blunt instrument, such as the dull end of a cooking skewer. During the cramming process most of the bubbles will be displaced, but you will still need to poke and top off for a few minutes to coax the stragglers out. The epoxy should stand proud above the surface and there will be fibers sticking out the top; just sand them off when cured. While this all takes a few extra moments, the results are worth in high load applications.

Bottom Line: Best Choice when strength matters.

Solid Fiberglass

So long as the glass is at least twice the fastener diameter, it should hold the full strength of the fastener. However, repeated removal will damage the threads. Drill the correct pilot hole size or the fastener will bind and break.

Bottom line: Screws will hold in solid glass, but they are not nearly as reliable as a bolt and nut.

Conclusions

Any filler reduces the ability of the epoxy to hold threads. It does this primarily by forming microscopic air bubbles that have no chance of escaping the thickened epoxy. This does not imply that the compressive strength or bonding strength has been reduced-colloidal silica is valid for through bolt and filet bonding applications. But it will fail in the tiny spaces around threads. Neat epoxy is brittle and prone to cracking; however, this did not reduce the strength much and is perfectly suitable for sealing holes for through bolts and most self-tapping screw applications.

The highest strength option, it turns out, is reinforcing the epoxy with fiberglass cloth. This combines the strength and bubble-free consistency of epoxy with the toughness and high strength of fiberglass, yielding the highest possible strength. In every test, the plug pulled out before the threads stripped. But are you better off with a stripped screw or a thumb-sized hole in the skin of the deck? You will have to answer that question, based on the nature of the installation.

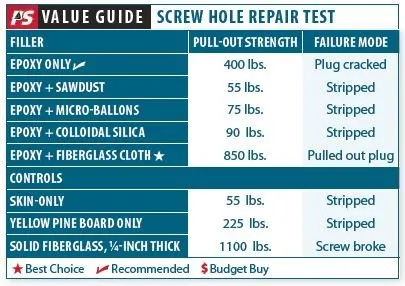

For this comparison, testers combined West Systems epoxy (with a slow hardener) and various thickeners to find the strongest combination. In one hole, no thickener was used. Three holes were filled with epoxy thickened with: 1) sawdust; 2) West Systems micro-balloons; and 3) Cabot M-5 colloidal silica. The fifth hole was filled with epoxy and then stuffed with 6-ounce fiberglass cloth. Screws were fastened while the material was still curing.

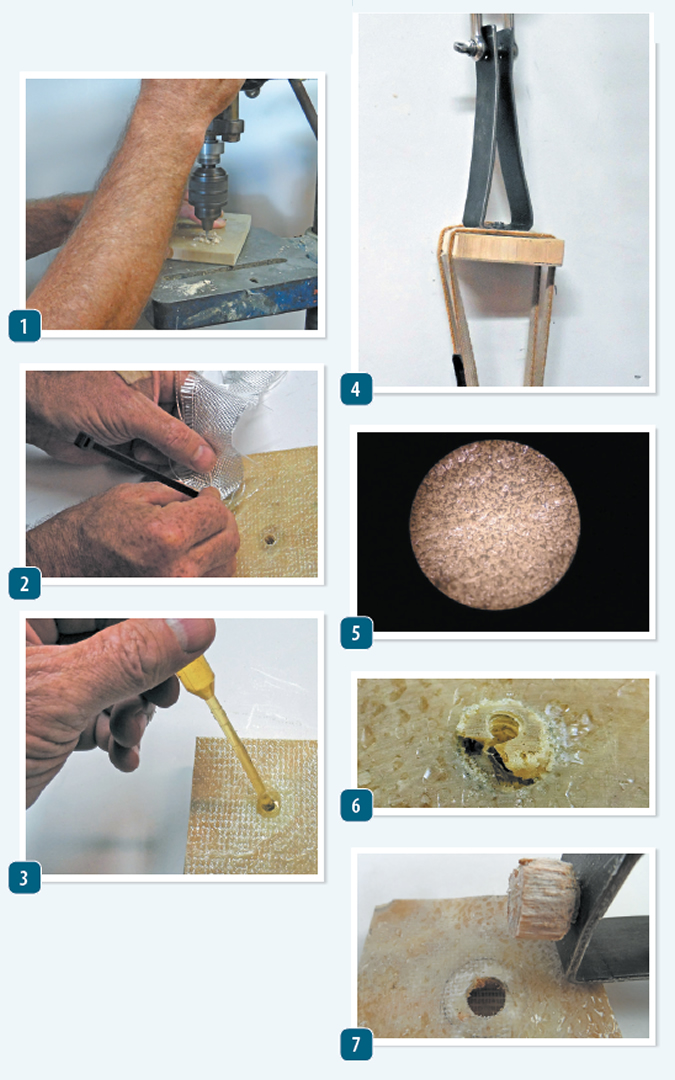

- We drilled 7/16-inch holes through the top skin and core only.

- An ordinary twist tie is used to force the fiberglass into the hole, which is already saturated with resin.

- One of the holes was filled with unthickened epoxy and allowed to cure.

- Our pull test apparatus was simple but effective. Testers pulled until the screw breaks or lets go, and recorded the load on the dynamometer (above and out of the picture).

- A microscope reveals the bubbles forming inside the epoxy thickened with silica. These bubbles weaken the matrix, making it easier for screws to pull out under load.

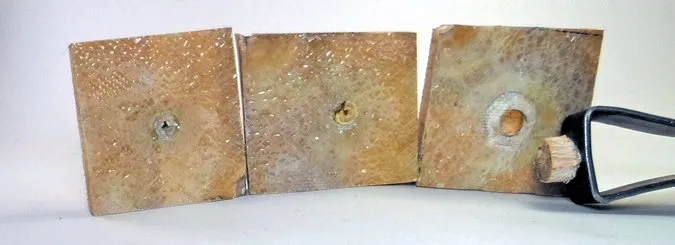

- The cohesive bonds in the cured unthickened epoxy gave out before the screw stripped out the threads. Notice the threads are still visible inside the repair.

- The balsa core split and tore through the fiberglass skin, providing the strongest repair.