This is the fourth article in a five-part series describing the rebuild of our 1982 Cape Dory 36 and how we turned it into a capable, yet simple, comfortable, affordable voyaging machine. In Part 1, I described the best practices we established to set ourselves up for a successful rebuild. In Part II, I described gutting the hull and designing and rebuilding the interior. In Part III, I described designing and building a new rig and deck layout improvements. In Part IV, I will describe the simple systems we use on our boat to keep the cost down and reduce maintenance and repair hassles and expenses.

SAILS

The single biggest purchase for the rebuild was new sails. I had budgeted about $4K to upgrade our existing sails. But, a new taller mast necessitated new larger sails (see “Part 3: Rebuilding a Cape Dory 36,” PS January 2023). I sold the old sails for $2,000.

We went with Doyle because they have a good reputation, there was a nearby loft, and the owner was a highly experienced sailmaker who supported my keep-it-simple approach. He had also cruised engineless earlier in life so he understood our needs.

We purchased an 8.6-oz. main with four full battens and two reef points, an 8.6-oz. staysail with two reef points, a 616 sf 1.5-oz. drifter, a 9-oz. trys’l, and a unique 8.6-oz hank-on genoa with a lower bonnet that would zip off to turn the sail into a working jib. We saved money by eliminating the furler, and our hank-on jib performs better and maintains its shape longer than a roller reefing jib. A hank on jib will also never fail you. I sold the 25-year-old Harken furler unit that came with the boat.

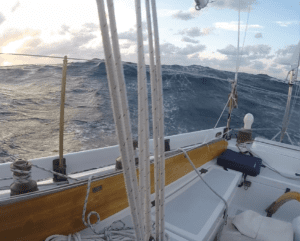

I’ve always enjoyed the timelessness of hauling-up sails hand over hand. It’s still exhilarating to hoist the jib, hear the whooshing bow wave, and feel the boat come to life while the wind-vane reliably steers the boat. Sure enough, handling the hank-on jib while singlehanding offshore at night is not for the faint of heart. Like most difficult tasks it’s mostly a technique driven skill. Sailors have done it since time immemorial. And, pulling off a sail change under difficult circumstances even when no one is watching is still immensely rewarding. There are downsides though, which will be discussed in the final series installment.

DINGHY

I have cruised with hard and inflatable dinghies. I hands down prefer a hard dinghy. It does not go flat, is seldom targeted by thieves, it creates opportunity for physical exercise, and it can be used with a sailing rig. We have owned a 9-foot Fatty Knees for almost 20 years. As described in Part 3, we stow and secure Sweet Pea inverted on the cabin top, aft of the mast, on dedicated chocks. To stow the sailing rig I fabricated leathered boots and rings which I whipped to the aft lower shrouds to hold the upper and lower end of the dinghy mast and boom vertically. Most people never notice them even when they walk down the side deck. With the dinghy along side we simply lift the mast up out of its boot and lower it into the dinghy mast partner. Nothing could be simpler. We bolt the rudder and daggerboard together and stow them ‘thwartship wedged between the dinghy gunwales with the bagged sail on this temporary shelf. The oars are strapped inside the dinghy. If necessary, the dinghy and its sailing components can be quickly launched from the cabin top as a single unit (see “Making the Dinghy Decision,” PS March 2021).

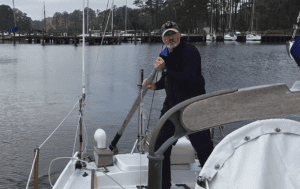

auxiliary propulsion aboard Far Reach.

SCULLING OAR

Without an inboard engine I built a western-style 14’10” sculling oar to move and maneuver the boat in calm conditions. Sculling is more than an oar—it’s a system that requires a well-built oar of the correct length and diameter, an oriental lanyard for the forward end of the loom, a strong oarlock, a way to mount it to the boat, and skill. The geometry has to be right for it to work efficiently and effectively. Even though I have sculled the Far Reach many times I would never recommend it to someone. Sculling, like singlehanding, has to be driven from within. If it appeals to you then it might be an option. There will be more on the sculling oar in Part V.

OUTBOARD ENGINE

We often carried a 9.9 hp Honda Power-Thrust four-bladed prop outboard with an extra long shaft. We mounted it on a clever custom made SS side mount swing arm bracket. The outboard bracket was designed and built for us by Yves Gelinas who also designed and builds the Cape Horn Windvane.

We used the engine in the marina or on a long narrow stretch of the Intracoastal Waterway when the sculling oar or sailing was not practicable. It worked very well on smooth water or a short chop. At wide-open-throttle it pushed our boat at 6 knots. At 4000 RPM we made 4.5 knots. It was a great alternative to an inboard but we could not use it with our side mount bracket off-shore or in semi rough conditions as it can be swamped.

Despite this, the only real draw back for me was that the outboard was unsightly on the port quarter of my otherwise lovely boat. James Baldwin (www.atomvoyages.com) has designed an engine well for a tilt-up outboard. The project requires substantial cutting and fiberglass fabrication around the transom area.

WINDLASS

I found a barely used ABI bonze manual windlass for $400. I took it apart, greased it, and installed it on a teak and G10 block on the foredeck with a large solid fiberglass backing plate. For ground tackle we purchased a 45-pound Spade anchor and 250-feet of 5/16” HT chain. We installed a small Danforth near the stern quarter with 250 feet of ½-inch three-strand rode led through a deck pipe and coiled on a purpose-built shelf in the port locker. In the bilge we stow a 35-pound spade anchor and a three-part 70-pound Luke storm anchor in dedicated racks and another 300 feet of ½-inch line in the forepeak accessible to the foredeck via its own deck pipe. We carry 60 feet of spare chain and an assortment of domestic made shackles. We also carry a surplus heavy duty 8-foot-diameter Bureau of Ordinance drogue with a galvanized domestic 5/8-inch swivel for heaving-to in extreme conditions (discussed in detail in Lin and Larry Pardey’s excellent book Storm Tactics).

PLUMBING

We carry 90 gallons of fresh water in four tanks. One 20-gallon tank is in the port cockpit locker on a high shelf close to the underside of the side deck. It is gravity fed to the head and fills, via petcock, a 3-gallon manually pressurized spray bottle that resides in its own cabinet next to the sitz tub. We add a kettle of hot water to the bottle for hot showers, and pressurize the bottle using the pump. The spray nozzle delivers an efficient warm shower while we’re in the sitz tub.

The remaining 70 gallons are located in the bilge in three tanks. We use classic Fyn-Spray brass galley pumps mounted at the galley and head sink. There are no electric pumps aboard. With the exception of the 20-gallon tank in the cockpit locker all the tanks are filled by running a hose from a DIY Baja filter (see PS March 20150. There is one deck fill to the tank in the locker as it’s directly under the side deck. I plumbed the tanks with ½” trident potable hose, simple plastic hose barbs, and PVC ball valves. I used PEX and Shark-bite couplings for the vent lines. The entire walnut cabin sole can be removed in five minutes. The tanks can be removed and sitting on the dock in 45 minutes. We wash the bilge out with a hose every year to keep the boat clean and smelling fresh.

THE SITZ TUB

I have showered on many different boats. Most are stand-up showers with a vinyl curtain. Everything gets wet. It’s stuffy when you are using it, and you constantly battle mildew because of the moisture. We eliminated the mess of a stand-up shower and built a sit-down sitz tub under the side deck with a removable bare teak seat. No curtain is required. It’s light, roomy, open and never smells dank because there is so much ventilation. With the foredeck hatch open it’s wonderfully breezy. The tub drains to the grey water tank. You can use it while sailing without fear of being thrown down. It’s comfortable and secure.

HEATER

We installed a stainless steel Refleks MK 66 heater with cast iron top mounted low just forward of the starboard settee and vented through a 70 mm flue to an on-deck smoke head. It’s jetted for kerosene instead of diesel since kerosene is what we carry on the boat. It is gravity fed from a 10 gallon tank in the starboard locker. Next to the watch seat is a pet cock installed in the kerosene fuel line used to fill our kerosene interior lamps and nav lights.

We also use a small cleverly designed Ecco fan that sits on the Reflex’s cast iron plate and pushes hot air through the boat. Our boat is well insulated and the Mk 66, the smallest heater Refleks makes, is more than adequate for our boat. It has eight settings and we have almost never gone above 2 or 3.

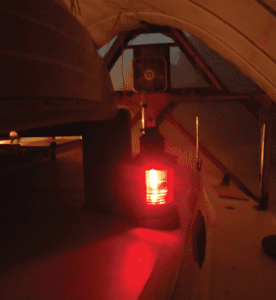

NAVIGATION LIGHTS

Because we did not install an engine, I had no way to generate electricity for navigation lights. So, I located a set of antique Perko kerosene nav lamps to include a 135-degree-arc sternlight and installed new burners that included glass chimneys so they will stay lit in high winds. Some argue they are not legal. My interpretation of the international collision regs (COLREGS), is that they are.

THE GALLEY

We installed a Force 10, three-burner stove with oven, fixed mount stove ‘twartship to reduce the likelihood of getting burned as you never stand to the side of the stove—the cook is forward of the stove facing aft.

If the boat were to suffer a knock down or came off of a wave at a severe angle and liquids came out of a pot, the liquid would go to port or starboard and not forward where the cook is standing. Also, the cook would not be thrown onto the stove.

Such an arrangement dramatically reduces the chance of a burn offshore. The stove was discontinued, though you can still purchase non-gimbled stoves, and we purchased it at half price. Mounting the stove in a non-gimbled manner freed up a lot of otherwise wasted space. Our galley configuration provided us with a 5-foot-long solid ash counter with full-length storage area below with shelves accessed via a sliding raised panel door.

As part of the deck projects, we designed and built, to American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) standards, a propane locker under the aft cockpit seat to hold three 10-pound aluminum bottles. It is vented above the waterline. Because we did not initially have electricity we had no way to run an electric solenoid shut-off for the propane. Instead we installed a UL-approved manual low pressure valve in the locker and connected it to a ½-inch copper water pipe and ran it forward to the galley under the cockpit seating, with a turn knob. We turn the gas valve off with the handle before we turn off the stove valve, shutting down the flame, thus we know it works.

BILGE PUMP

We purchased an second-hand but unused Edson bronze #117 gallon-a-stroke bilge pump (a consignment shop find) next to the watch seat. I plumbed it to a selector switch between a hose to the bilge and one to the grey water tank. We use it every day to pump the grey water so we know it works. It’s reliable, doesn’t require electricity, and moves a lot of water quickly. Because it does not use electricity and is not submerged in salt water (our bilge is totally dry) it can’t cause electrolysis.

CAPE HORN WINDVANE

We chose a self-steering windvane designed and built by Yves Gelinas the owner of Cape Horn Marine Products. Yves designed and built the prototype for his Alberg 30, then tested it on a one-stop, round-the-world voyage through the Roaring 40s. I felt confident it would work well on our boat since the design of the two boats is nearly identical. Yves encouraged us to run the control lines underdeck and through our old steering quadrant, left over from the wheel steering I removed. The installation is clean, uncluttered, and works perfectly.

SOLAR

Initially we had no electricity. But, I was challenged by my wife to find a way to charge a lap top when my kids required one for home-schooling. To keep it simple I installed a 30-watt Gantz semi-flexible solar panel on a 10-foot-long cord (the Gantz is no longer available) wired to a deck connector then down the interior saloon stanchion. I married it to a Genasun 5-amp MPPT controller and to a 100-Ah Lifeline AGM battery. Thus, before we made our first voyage we had the capability to charge our phones and the laptop.

DEPTH SOUNDER

Because we did not have electricity at the time I put together a lead line on a 60-foot line. Then I made an extension to easily add another 60 feet if needed. I built a special mounting bracket in the lazarette to hold the leadline and make it easily accessible when needed.

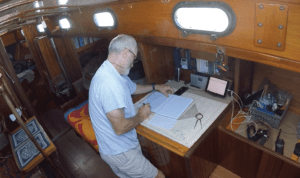

NAVIGATION

My navigation choices reflect my philosophy of what brings me enjoyment—using my brain as best I can and relying on equal parts art and science. Thus, I installed no dedicated chart plotter. I carried then, as I do now, paper charts, a Garmin GPS 76, and HO 249 Volumes 1-3, an almanac, and my sextant. Before I singlehanded back to North Carolina from St. Maarten, I installed a Vesper Watchmate 850 AIS transceiver. Although I occasionally use the iNavX navigation app on my iPad mini, my real focus is celestial navigation.

I continue to improve my knowledge of the sun with a running fix and reducing star shots to achieve a true fix. I check my accuracy against the GPS and find I am normally within 1-3 miles. I’m not an expert, but I am improving all the time. I find Celestial navigation infinitely rewarding. My deep dive into celestial has only furthered my respect for the sailors of previous generations who had to master it to make successful ocean passages.

Most sailors unfamiliar with celestial navigation are intimidated by the sight reduction process, which in reality is pretty simple. The real challenge is taking the shot on a pitching deck and reducing the sight manually when the boat is jumping all around. Just as with many outdoor activities—backpacking, hunting, fishing, etc.—the challenge is part of the fun.

I purchased a new Sony GR7600SW portable HF/SSB receiver for $120 and added a DIY long wire antenna to improve reception. I can listen to the High Seas Forecast as well as download U.S. Coast Guard weather faxes via a simple app on an iPad. I also purchased a Spot Gen 3 one-way satellite GPS transmitter. With it, I can send a GPS location to weather forecaster Chris Parker (www.mwxc.com) who transmits the forecast to us via our receive-only SSB. Often I can be 1,500 miles from Parker and hear him on our small HF as clearly as if he is talking to me in the saloon of the Far Reach.

EPIRB

We carry two emergency beacons. Our primary EPIRB is a McMurdo Fast Find Max GPS EPRIB registered to our boat that transmits on internationally monitored government GMDSS/SOLAS satellite network. I chose this model because I can change the battery and test it myself. The SPOT has a SOS capability as part of its base feature that transmits back on a privately owned satellite network that SPOT HQ monitors. SPOT hands off any alerts to the USCG (see “Is the SEND Device Message Loud and Clear?” PS July 2012)

The systems that we use on our boat reflect our philosophy to keep it simple yet effective and to keep the focus on the things that make sailing fun and enjoyable.

Next month is the final installment where I will share how our planning worked out in the real world. What worked, what did not, and what changes we have made during 11,000 nautical miles of sailing.

CONTACTS

CAP HORN, www.caphorn.com

FATTY KNEES, www.fattyknees.com

EDSON, www.edsonmarine.com

FORCE 10, www.force10.com

FYNSPRAY, www.fynspraypumps.com

GARMIN, www.garmin.com

INAVX, www.inavx.com

HARKEN, www.harken.com

GENASUN, sunforgellc.com

LIFELINE, www.lifelinebatteries.com

MCMURDO, www.seasofsolutions.com

SPADE, www.spadeanchorusa.com

SONY, www.sonymarine.com

SPOT, www.findmespot.com

VESPER, www.vespermarine.com

I love your philosophy on this build BUT…. I don’t agree with the Outboard engine option. But let me explain why. Even a new outboard won’t last as long as a good inboard Diesel engine. So overnight the life of your boat you will go through more then one out board. Second reason is as you stated rigging up a outboard mount takes a bit of design and often is useless offshore. Another reason is unlike a inboard diesel you can’t install a high output alternator. As much as I hate motoring vs sailing it is nice to do things that like run the water maker or charge up the batteries while motoring for a few hours. Now I do still consider my engine a auxiliary and don’t use it if it is possible to sail. But a boat designed for a inboard with a outboard for me just lowered its resale value as well. And lastly to rework the hull to glass ina outboard well is even worse as again that is a lot of work and yes cost to install a engine that won’t outlast a good inboard.

And lastly and the most opinionated reason I feel if you make the decision to go engineless the GO Engineless! A outboard is cheating you essentially are conceding you really want a engine but for some reason you only objected to a inboard Diesel which would actually outlast a outboard and provide more utility then the outboard anyway. Yesi know a outboard is cheaper initially but Outboards don’t last 20-30 years a well maintained inboard marine Diesel well out last any outboard.