When small computers started to become popular, experts spoke knowingly of the “paperless office.” When the year 2000 rolled around, pundits said that the world, along with its computers, would crash. And when fiberglass boats began to reach the market, knowledgeable people spoke confidently of “maintenance-free” hulls. So much for predictions.

It is true that compared to wood there’s a lot less maintenance required of fiberglass. But its high-gloss shine has also raised boat owners’ expectations. And so, after a few years, when the glass begins to dull and the color starts to get streaky, most owners want to do something to remedy the situation. The traditional material for restoring gloss is wax; together with an abrasive polish (if needed), wax can do a fine job of reviving your boat’s appearance—for a season, at least. The long-term solution is to paint with a two-part linear polyurethane such as Awlgrip, Imron or Interthane.

In more recent years, a mid-term solution has appeared—so-called polymeric “restorers” that are growing in popularity.

We’ve been testing these hull restorers for several years now and, despite some initial reservations, we’re becoming more appreciative of how well they work. They’re not miracles—most are intended to be re-applied yearly—but used properly they can take a blotchy, dull fiberglass hull and give it a gloss that lasts for at least a year.

During this time there have been occasional complaints from readers that these products can give the hull a yellowish cast. Unfortunately, our early test panels were taken from the hull of a wreck that had a yellow gelcoat. This year, we applied eight different hull restorers to white fiberglass panels, and set them out into the weather to check these assertions.

How ‘Restorers’ Work

The two aspects of a hull’s appearance that can be helped by the owner are gloss and color uniformity. When the boat is new, the gelcoat, which derives its color from fine particles of opaque pigment dispersed throughout the gelcoat layer, has a very smooth surface. It’s glossy because, as happens with a mirror, rays of light that strike the surface from any given angle are reflected back in the same direction. As the fiberglass ages, sunlight and weathering change all this. The pigments—at least the outer layer—tend to fade and discolor. Not all pigments fail at the same rate. Unfortunately, the most durable ones are also the dullest colors, while the bright colors fade most rapidly. At the same time, the gelcoat surface becomes microscopically pitted and roughened, so that light striking the surface is reflected in random directions instead of unidirectionally. The result? A dull, faded, blotchy appearance.

What can be done? Well, because the degradation of the pigment occurs at its outer surface, the first step is to remove that outer surface, exposing fresh pigment. This is purely a mechanical scraping or grinding process, usually done with a mild abrasive polish or rubbing compound. Sandpaper would work, but it’s too coarse for the job, as you wish to remove only enough material to present a fresh layer of pigment.

Polishes and compounds consist of fine particles of abrasive suspended in a liquid or paste; polishes use extremely fine particles of a not-too-aggressive abrasive, while rubbing compounds have coarser and harder particles. The more badly weathered the surface, the more material you must remove. Slightly weathered hulls respond to polishes, while more severely weathered hulls call for compounding, followed by an application of polish.

Once the color is bright and uniform, the next step is to polish until the surface is smooth. It’s well nigh impossible to bring back the initial high gloss, but you want it to be free of scratches.

The last step is to apply a transparent film that will fill microscopic pits and craters, and leave a very smooth, highly reflective surface. That film is what fiberglass restorers are all about.

There’s no trick to restoring a high gloss to a polished fiberglass surface—almost any liquid, including water, will do it. The trick is to find something that will last, something that will cover the fiberglass surface for an extended period of time without developing a pitted surface of its own.

The time-honored approach is wax. Waxes, especially the harder waxes like carnauba, do a good job of providing a smooth, high-gloss surface film for a while, at least. In our experience, the best of them will keep a glossy surface for up to a year, much less with 12-month tropical exposure. Waxes are polymers—large molecules formed by combining a number of smaller molecules. The larger the molecule the more durable it is (and the more difficult it is to apply).

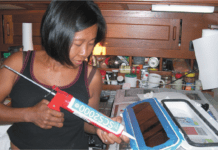

The products known as fiberglass restorers carry this concept a step further. They consist of resins of higher molecular weight that provide a harder and more durable film than can be achieved with wax. All the do-it-yourself fiberglass restorers tested consist of water-based emulsions of acrylic or acrylic/urethane resins. The resins are in the form of tiny droplets that are suspended in water. When applied, the water evaporates and the droplets flow together to form a clear film. These emulsions have low, almost waterlike, viscosities and dry rapidly. They require multiple coats, but application is easy and successive coats can be applied after only a few minutes delay. Typical instructions call for about five coats, with three maintenance coats each year.

Microshield is the only product tested not intended for do-it-yourselfers. The manufacturer, who says it will last for eight years, prepared the panels for us, so we have no experience applying the product.

The Tests

To derive a measurement of each product’s gloss retention, a yardstick (of our own making) is placed vertically on top of each panel, with 0 at the bottom. The higher the number reflected on the surface of the panel, the better its gloss retention.

Last year, after 18 months of exposure to New England weather on south-facing racks, the professionally applied Microshield showed the best gloss retention. It was followed (at a considerable distance) by New Glass, Poli-Glow and Vertglas. After an additional six months, these three showed little additional change.

Maintenance coats were applied to portions of all the panels (except Microshield). On each panel, one portion was stripped to the gelcoat (we had no trouble stripping any of the products). On another portion we simply applied additional product to the existing film. With one exception, there was little or no difference between the panel sections that had been stripped and recoated and the ones that had only been recoated.

Sea Glass Sea Protector, applied as a maintenance coat to an un-stripped surface, gave a slightly milky appearance when compared to a film applied to a stripped surface. After another six months, the appearance of the re-coated panel sections tracked well with previous findings on the initial treatments: New Glass, Poli-Glow and Vertglas once more excelled.

Because of the questions concerning whether these hull restorers would discolor or yellow with time, we applied each of them to fresh white fiberglass panels. In order to retain a “before” to compare to the “after” results, we masked off a section of each panel with aluminum flashing to protect it from sun and weather. Results? After six months of exposure we could see no signs of yellowing.

Conclusion

The best of these products work, as long as your expectations are realistic. They will definitely make a dull finish shine and—if you’ve been thorough about compounding and/or polishing—you can get your boat fairly close to a new boat appearance.

They won’t last as long as new gelcoat, however. If you opt for a hull restorer, you’d better figure on a yearly maintenance coating. Having said this, we should point out that a hull restorer is considerably less expensive than the two options that can give better results: painting your hull with a two-part polyurethane paint or simply buying a new boat. A professional paint job will likely set you back about $100-200 per lineal foot. Less, of course, if you do the job yourself, but brush jobs never equal the look of spray paint.

You can use a do-it-yourself hull restorer for $35-$60 total, plus the value of your labor. New Glass, Poli-Glow or Vertglas, the longevity champs, should provide reasonable gloss for a season in almost any climate. You’ll have to apply three maintenance coats a year, but all three products dry in minutes, so that you can recoat by working your way around the boat three times.

Microshield is intermediate in cost between a paint job and a do-it-yourself hull restorer. The cost of a Microshield job depends upon the size and type of your boat; we couldn’t get a simple, general estimate from the manufacturer. If you’re interested, contact them directly. And be sure to get a clear, explicit warranty on the job. Unlike the other products tested, Microshield does not strip easily, and any application that’s less than satisfactory is going to be difficult and expensive to correct. We’ve received one report of problems; a warranty issued by a reputable applicator is a good precaution.

In addition to reports of user-applied products going milky or yellow, we’ve also heard of flaking and cracking. Still others claim that stripping is difficult.

After almost seven years of testing this type of product, we’ve never encountered any of these problems, though for stripping, you must have the right product.

We suspect that the root of any of these problems lies in the preparation of the fiberglass surface before the restorer is applied. Water isn’t a problem, but oil, grease and dirt are. Many commercial rubbing compounds have an oily base which must be removed before the restorer is applied. Better yet, only use abrasives recommended by the restorer’s manufacturer.

Just as we were going to press, Microshield, which had told us it was best used on hulls still in good condition, disconnected its phones. All attempts to locate them failed. If they resurface, we’ll advise readers.

Fiberglass ‘restorers’ are best thought of as remedies for weathered hulls rather than preventatives. If your boat is already shiny, just wax it. And if it’s really gone, paint it.

Contacts- Sea Breeze, Rolite Co., 596 Progress Dr., Hartland, WI 53029; 414/367-2711. Vertglas, Lovett Marine, 682 W Bagley Rd., Berea, OH 44017; 800/636-7361. New Glass, KAS Marine, 6 Lago Vista Pl., Palm Coast, FL 32164; 904/829-3807. Sea Glass, Port of London, 6101 Dory Way, Tampa, FL 33615; 813/855-5983. TSRW, Edgewater Distributing, 55 NE Bridgeton Rd., Portland, OR 97211; 503/282-7006. Higley, Higley Chemical Co., 40 Main St., Dubuque, IA 52001; 319/557-1121. Poli-Glow, Poli-Glow Products, 15476 NW 77th Ct., Miami Lakes, FL 33015; 800/922-5013.