Calling for help at sea is easier than ever before. And thats part of the problem.

Rescue missions prompted by distress alerts from emergency position indicating radio beacons (EPIRBs) have topped 6,000, and that number continues to grow. But while these rescues grab headlines, there also have been a small number of failed attempts, and these tragic incidents raise some questions about both the hardware and the search-and-rescue process. Not wanting to make “very good” the enemy of “perfect,” we tread carefully when it comes to discussing search-and-rescue operations. Nevertheless, every sailor should have a good working knowledge of how the International Maritime Organizations (IMO) worldwide safety network functions and what it takes for the rescue puzzle to come together.

Photos by Ralph Naranjo

First operational in 1982, the satellite-based COSPAS/SARSAT search-and-rescue network built upon the system pioneered in the aviation industry that used 121.5 /243 MHz beacons called emergency locator transponders (ELTs). The maritime offspring of ELTs, the rugged emergency position indicating rescue beacons soon became the distress alerting tool of choice for mariners worldwide. The frequency switch from the 121.5/243 MHz to the current 406-MHz system saved even more lives by linking each EPIRB to a unique hexadecimal code. This greatly reduced the number of untraceable alerts. The addition of GPS chips brought another significant step. These “GPIRBs” broadcast precise position data as well as allow for Doppler-shift position-finding.

At the receiving end, more effective alert processing has shortened the response time of search-and-rescue missions. Many people are alive today thanks to a near seamless link connecting a beacon signal that bounces from a satellite to a Local User Terminal (LUT) to a Mission Control Center (MCC) and then on to the Rescue Control Center (RCC) responsible for the search-and-rescue mission.

The flip side of this success story is a rising number of false alarms and infrequent but recurring cases of beacon failure. Consider this staggering fact: 96 percent of all EPIRB distress signals are false alarms. Eighty-five percent of these are sorted out at the RCC level where phone calls to contacts listed on the beacons registration form usually validate or nullify the distress situation. In the remaining cases, some tough decisions must be made. With only 4 percent of all alerts being actual distress situations, its no surprise that a helicopter is not lifting off the moment a distress message reaches the RCC.

Case Studies

Anyone putting blind faith in their 406 EPIRB should consider two recent incidents in which registration numbers were somehow incorrectly added to the United States 406 MHz beacon registration database. These apparent clerical errors ultimately delayed rescue missions. The concern over additional miscues has prompted the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA) to encourage beacon owners to check their registration data online. The easy-to-navigate website www.beaconregistration.noaa.govoffers step-by-step guidance.

Another all-too-common problem is the malfunction of automatic Category I “float-free” EPIRBs, beacons designed to be fixed to the stern rail or other on-deck location. These units auto deploy and switch on if the vessel founders. They rely upon electrical contacts that automatically activate the device when it becomes submerged. Unfortunately, their sensitivity can lead to a false alarm when doused by a wave, chilled by a freezing rain, or being bumped and jarred in their container.

To prevent such unwanted beacon broadcasts, manufacturers install magnets in the case that cause a magnetic switch to open the circuit while the unit is in its protective housing. However, this technology is vulnerable to “bracket de-coupling,” in which corroded magnets or installation errors prevent the magnets from working.

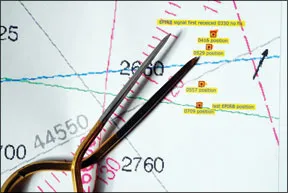

In some cases, such as that of the 54-foot sloop Flying Colours, the details about a beacon failure will never be known. The Little Harbor 54 was lost in a brutal storm off Cape Hatteras in May 2007. U.S. Coast Guard records show that an EPIRB signal was received from the boat at 3:30 a.m., but a position fix was not established until 4:16 a.m. The EPIRB signals ended at 7:09 a.m., and no sign of the vessel or its four-person crew was ever found.

In the same storm, the 44-foot Beneteau Sean Seamourwas capsized and dismasted. The sloop took on water, and the four-person crew abandoned ship as the vessel sunk.

The EPIRB that the owner had purchased overseas was re-registered and inspected in the U.S. Its distress alert was processed and forwarded to an East Coast RCC. But when the RCC checked the database, the owner listed was a fisherman in the Gulf of Mexico. When the RCC called the registered contact, the fisherman reported he was safe at home and in bed. The signal was then, apparently, discounted as a false alert.

Fortunately, the skipper of Sean Seamour had a second 406 EPIRB on board that formerly had been carried aboard his previous sailboat Lou Panti. This EPIRB automatically activated when it was carried away by a breaking sea. A skilled USCG helicopter rescue crew was vectored to the signal of the Lou Pantibeacon, saving the crew of

Sean Seamour.

Aside from highlighting some significant problems with the beacon registration and signal verification system, the incident proved how valuable a second beacon can be.

Beacon Alternatives

Without question, a 406 EPIRB should be the mainstay of your distress signaling game plan. Its a tried and proven system with worldwide coverage, and it has been in place long enough to work out most hardware bugs. Despite a less-than-perfect record, it remains a mariners best first choice. Whether to choose an auto-deploying model or a manually activated unit is a tougher question to answer.

As mentioned, the external water- sensing contacts and control magnets on Category 1 units can create a false alert. Additionally, violent seas can sweep a Category 1 EPIRB out of its bracket. Even so, auto deployment may be the best bet in the chaos of a collision or capsize. Many sailors prefer to keep a manual unit in an easily accessible ditch kit or grab bag, but climbing into a life raft and leaving the beacon behind can have catastrophic consequences.

Whichever you choose, regularly check the unit for signs of deterioration, noting the battery expiration date. While these units are built to survive extreme cold, never leave an EPIRB aboard while your boat is in winter storage. At the recommended intervals, test the units ability to transmit by following the manufacturers procedure, making sure that the switch is pushed to the “test” position (not “activate”). Each test consumes battery capacity, so keep both the frequency of testing and duration of transmission to a recommended minimum.

Today, the 406 beacon relies upon low earth orbiting (LEO) and geosynchronous satellites, but a new technology that will harness middle earth orbit (MEO) satellites is scheduled to go online in 2013. The existing 406 EPIRB program will overlap the implementation of the new system, even if the latter is delayed.

EPIRB

More and more, new EPIRBs feature an internal GPS receiver, a big advantage. Once satellites are acquired, these units will send a lat/long fix as well enable position tracking via Doppler shift. ACR offers a dual GPS unit that eliminates the lag time in position reporting caused by delays during initial satellite signal acquisition. The EPIRB is interfaced with the onboard GPS, keeping the beacon aware of the current position, and allowing the first emergency signal burst to carry an accurate lat/long.

Bottom line: In an emergency, a GPS-equipped EPIRB is well worth its capital outlay. Be aware that the batteries for some older models are very expensive or have been discontinued, so units that use these batteries might not be the bargain they appear to be.

Personal Locator Beacon

The little brother of the 406 EPIRB system is referred to as a personal locator beacon, or PLB. It includes a GPS chip and all of the attendant broadcast functions, including the 121.5-MHz homing signal. One of the key differences is that PLB spec calls for a 24-hour signal lifespan while the conventional EPIRB must deliver a 48-hour transmission under the same temperature and battery age constraints.

The latest iteration in PLBs combines the public-sector rescue functions with private-sector messaging capabilities. Introduced this year, the ACR Aqua-Link View Personal Locator Beacon with onboard GPS features a digital readout that can provide visual feedback regarding proper deployment, confirmation that the beacon is working properly, GPS location, remaining battery power, and more. Those who subscribe to ACRs www.406link.com messaging plan can also send an “Im OK” message to pre-

determined contacts when they perform a GPS self test.

Those who opt to subscribe to the messaging service should be aware that the advanced self-testing will cut into the battery life of the unit. The unit is programmed to cutoff self-tests at a pre-determined number to ensure it will still have sufficient battery life to meet the 24-hour emergency transmission requirement.

When choosing a unit, it is important to know that some do not float. The MicroPLB from Microwave Monolithics Inc., for example, doesn’t float, but its extra density is put to good use. The PLB meets the 48-hour endurance spec for EPIRBs and has been in governmental use for 11 years.

Pocket-sized and convenient to carry, these more modestly priced beacons are rapidly becoming a favorite among mountaineers, back-country skiers, and adventurers on land and at sea. Whether rescuers will be able to cope with the inevitable increase in false alerts remains to be seen.

Bottom line: Built to exacting standards and designed to mesh neatly with government search-and-rescue operations, a PLB would be our first choice as a backup for a 406 EPIRB.

Trackers With Emergency Button

The private sector has jumped into the portable beacon domain, and the first widely marketed product has been the Spot Messenger, a reliable and efficient tracker with an interesting emergency call feature . In a nutshell, the unit engages a privately owned constellation of LEO satellites to transmit a time-stamped GPS position and a preset phrase such as “All OK.” The downlink goes to the companys headquarters where position reports are sent via e-mail to up to 100 addresses previously chosen by the trackers owner. Progress can be followed on Google Earth maps.

The Spot also features an emergency button that is to be used only in situations of imminent threat. It alerts the message-handling crew to immediately pass the situation report on to an appropriate agency, and here lies the rub. Because the SPOT system is not part of the COSPAS/SARSAT, direct insertion of this message at the right point is not always so easy.

Bottom line: For sailors staying within its coverage area, the SPOT is a good backup communication device, but it is no substitute for a PLB or EPIRB.

Sat Phones

These devices arent waterproof and do not directly link to a network of search-and-rescue services, but they have played a valid role in many high-seas rescues.

One reason people like to use satphones is that they are familiar with portable phone technology. The two-way communication option makes them a great candidate for inclusion in an abandon-ship bag. Bring along a waterproof bag or special case for the gear and be sure to jot down the telephone number of the Coast Guard communications center and rescue control center for the areas youll be sailing.

Sometimes a familiar alternative, though perhaps not the ideal choice, can save the day in an emergency situation. At least thats how it has played out with cellphones aboard several commercial fishing boats where crew members have called home on cell phones and said, “Honey, call the Coast Guard…”

Bottom line: While we generally advocate marine specific gear, using a Sat phone as a backup to an EPIRB is a viable option. Sat phone transmission, cell-phone calls, and VHF mayday broadcasts wont interfere with EPIRB signal propagation.

Conclusion

The bottom line is that when youre in serious trouble and lives are at risk, outside assistance may be your last hope for survival. The sooner a distress situation is verified, the sooner an SAR mission is put into effect. Unfortunately, the high false-alarm rate associated with EPIRBs can contravene this goal, as valuable time is lost trying to confirm a distress signal. Two means of satellite signaling for help is definitely better than one, but which is the best second choice and is it worth the expense?

The few-hundred dollar investment in a secondary tracker/beacon can increase the odds for success. So can a Sat phone call made directly to a rescue center. But in our final tally, when it comes to our choice for the right safety back-up satellite communications device, our first choice would be a PLB. Its big brother/little brother relationship with the EPIRB and its standalone autonomy are big pluses, so when all is said and done, our “safety hedge” remains within the COSPAS/SARSAT family.