Loss of steering may well be the most common cause of rescue for boats sailing offshore, but the problem is even more common inshore where there is more debris to hit. An emergency rudder is always possible, but for most of us, extra gear to rig, cost and strength concerns most often render the option impractical. Wrestling an emergency rudder into position will be physical and possibly dangerous in rough conditions. In the case of a catamaran it is simple to disconnect a rudder that is jammed straight, but what if it is jammed hard over, as in the loss of the Alpha 42 Catamaran Be Good Too in 2014?

Tests have been published using drogues for steering with the rudder either removed or locked in position, showing that in moderate weather even sailing to windward is practical as long as sails were adjusted in concert and the drogue position was adjustable. Our questions go further. What if the rudder has jammed an angle? Are all drogues appropriate for this purpose? How do you choose the best size?

Our goal was not only to test rigging methods and drogues, but also to quantify how it sailed under drogue steering control. What rigging works best, what size drogue is required, what courses can we sail, how stable are they, and how quickly will we get home? In “How Much Drag is in a Drogue?” we collected data for a range of commercial drogues. That information will help you translate out findings into a steering drogue that will work for your boat.

What We Tested

For steering, a relatively low-drag device is required. While parachute-type sea anchors and high-resistance or stopping drogues may be good for surviving a severe storm, they aren’t useful for getting to port with no steering. See “Improve Steering Efficiency” below. As we will learn, if the drogue produces too little drag, we can’t control the boat in all circumstances; too much drag slows us down and prevents progress to windward. Thus, we tested the Seabrake GP24L, Galerider 30, Delta Drogue 72, and a towed warp.

We tested using a 32-foot PDQ catamaran with the rudders still in place, either locked straight or at 60 percent to one side to simulate a single rudder jammed hard-over. Each of these simulates an actual occurrence, and even on monohulls, bent and jammed rudders are more common than lost rudders. Of course, losing the rudder entirely presents a slightly different case, since the rudder provides some portion of the lateral plane as well as steering control. Much depends on the underwater profile of the boat and the sail plan, so you will need to practice and amend our findings to fit your boat.

How We Tested

We deployed each device on 100 feet of polyester double braid rope, weighted with 8 feet of 5/16-inch chain, and towed them at two speeds (3 knots and about 4-5 knots) to develop a speed-versus-drag relationship.

We then deployed each device from our test boat using a bridle formed by a pair of spinnaker sheets and sailed a variety of courses in a variety of wind speeds up to 30 knots sustained in semi-protected waters, building a rough speed polar for each device. We also compared performance with different the bridle attachment points and rode lengths.

For initial testing we deployed the drogues from a bridle consisting of spinnaker sheets led to turning blocks at the toe rail about 8 feet forward of the transom, varying both bridle position and sail trim until the best speed and course were attained. We then sailed each course for at least 10 minutes, collecting averages and judging stability.

The result is an overall picture of how the boat sailed around the course with each drogue. We then practiced with several of the drogues, deploying them on longer rodes in stronger conditions, using both the genoa sheet bridle and a bridle formed by deploying with a single line from one winch, and then deflecting it to one side using a snatch block and pendant led to a winch on the other side.

Drogue Selection

How to pick the best size drogue for emergency steering? In snubber testing we found our 34-foot catamaran test boat to be roughly equivalent to the ABYC 40-foot monohull in terms of windage, which gave a lunch hook anchor load of 300 pounds. Our recommendations for winds up to 20 knots is to pick a drogue that produces about 60 percent of the ABYC lunch hook load when towed at 4.2 knots. For stronger conditions, up to gale force, go up 100 percent of the AYBC lunch hook load; the larger size can be de-powered by using on very short scope, within limits.

Following this logic and our on-water experience, the Seabrake 24 and Delta Drogue 72 were well sized for our 34-foot test boat in moderate to fresh conditions. The Galerider 30 was wonderfully smooth and fun to use, but it was over powered in winds above 15 knots (the Galerider 36 is the correct size for the test boat).

Since all products were tested in moderate conditions on a single boat (34-foot catamaran), our recommendations should be adjusted to reflect the boat you have and conditions you anticipate. In “How Much Drag is in a Drogue?” we presented drag data and more detailed reviews.

Delta Drogue 72, Para-Tech Engineering

Based on an equilateral triangle of fabric, the Delta Drogue 72 is dimensionally similar to the other units in the test (the size designation is related to the side of the triangle and not the inflated diameter). It did have the occasional bad habit of skipping out of the water when overloaded at short scope, but not fully, and it very quickly re-engaged, always before any effect on course was noticed. The elegantly simple design is functional, well-proven, and strong.

Bottom line: Though a simple cone drogue may be cheaper, this represents the Best Buy in a real offshore drogue.

Galerider 30, Hathaway, Reiser & Raymond

Providing by far the most consistent drag at varying rode length and in waves, it was the tester favorite. While other drogues produced wildly fluctuating drag forces both under water and when near the surface, the Galerider was remarkably stable under water and by far the least affected by surfacing.

Our sample drogue was a 30-inch diameter size, and a 36-inch diameter was prescribed for our test boat. As a result, the we had trouble maintaining control with the undersized drogue in higher wind speeds. While added weight is not required for speed limiting use in storms, Galerider does recommend a short length of chain for steering use, primarily to allow it to be pulled very close behind the boat and still stay in the water. Considering the long service history of the unit (over 1000 units over 20 years), durability has generally been very good.

Bottom line: In all but the windiest conditions, the Galerider excelled. We have no doubt a larger diameter would have fared better. It is our Best Choice for emergency steering.

Seabrake 24

Although a little too large for light wind emergency steering, the extra drag was appreciated with the wind over 20 knots and when the rudder was locked to one side. Compared to the Galerider, it was less stable when towed on extremely short rode to reduce drag, but still functional and quite stable with 50-100 feet of rode.

Below 10 knots we were able to fly the chute at angles below 150 degrees true. Speeds in stronger winds include wave effects but not surfing. The Seabrake may have been faster in light winds if we had hauled it to very short scope, but that was not what we were testing. We did observe this, however; drogues pulled in close were faster, but less stable. We believe the Galerider would be more stable, since it does not skip.

Bottom line: Recommended for larger boats and for stronger conditions in smaller boats.

Small Shark, Fiorentino

Perhaps the easiest to deploy, it is compact for the drag produced, packs very small, does not require chain in front of the attachment (it does require a tail weight, typically a small mushroom anchor), and is easiest to get in the water. The Small Shark, with the mushroom anchor at the base, gets strong marks for ease of deployment; just heave it off the back.

Bottom line: Durability, easy deployment, and small size earn a Recommended rating.

Warps and Chain

Boats have sailed impressive distances with rope, chain, anchors, and fenders linked together to make a jury-rigged drogue. We tested just two 100-foot x ⅝-inch lines with 30 feet of ⅜-inch chain between them.

Bottom line: Not enough drag to do anything worthwhile unless a lot more stuff is added.

Conclusions

We always thought drogues were only for ocean passages and dangerous storms, until we struck a log and felt the helplessness of no steering and the closeness of a lee shore. We learned that loss of steering is a coastal sailing risk as well. Fortunately, a drogue and the knowledge to use it can restore a useful level of control in minutes.

Steering is more limited and laborious than plain sailing, and you wont point as high, but you can stabilize the boat to hold a course on most points of sail. With even low engine RPMs as a boost, you can sail most courses in moderate weather. Drogues can also temporarily replace a failed autohelm on downwind courses, although speeds are reduced; setting an retrieving a drogue in moderate conditions for this purpose is not difficult, and could be well worth the effort to gain a rest period. We were happy with spinnaker sheets for controls, though we suspect a turning block location at the point of maximum beam would better suit monohulls.

We strongly suggest practicing with the boat you have; you may find different rigging works better and re-rigging once the drogue is in the water can be very difficult. Our testing was limited to sustained winds 30-35 knots and wont pretend to know how emergency steering works beyond our experience. However, steering problems can also occur in moderate conditions, either the result of a collision, or in the aftermath of a storm, where a boat that has otherwise come through with minimal damage is prevented from heading to shore by one damaged appendage. We think steering drogues address these problems, and thus make sense for all sailors.

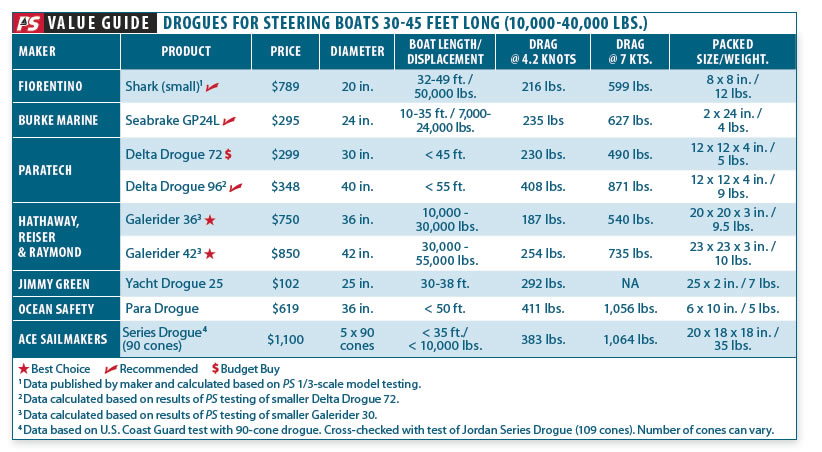

The above table lists drogues recommended by their manufacturers for boats that generally fit in the 30- to 45-foot range. This is an estimated size, and the broad range of boats in this category—stretching between a Catalina 30 to a William Garden Vagabond 47—illustrates the importance of consulting manufacturers and researching other reports when matching a drogue size to a boat. PS tested five of the above drogues. The source of other data is noted in the table.

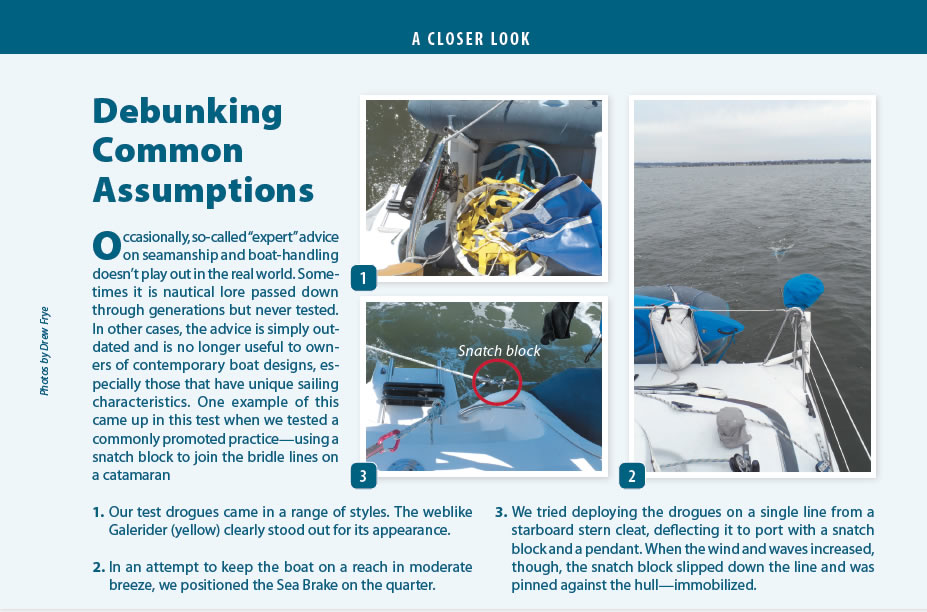

Occasionally, so-called “expert” advice on seamanship and boat-handling doesn’t play out in the real world. Sometimes it is nautical lore passed down through generations but never tested. In other cases, the advice is simply outdated and is no longer useful to owners of contemporary boat designs, especially those that have unique sailing characteristics. One example of this came up in this test when we tested a commonly promoted practice—using a snatch block to join the bridle lines on a catamaran

- Our test drogues came in a range of styles. The weblike Galerider (yellow) clearly stood out for its appearance.

- In an attempt to keep the boat on a reach in moderate breeze, we positioned the Sea Brake on the quarter.

- We tried deploying the drogues on a single line from a starboard stern cleat, deflecting it to port with a snatch block and a pendant. When the wind and waves increased, though, the snatch block slipped down the line and was pinned against the hull—immobilized.

This article was first published on 22 May 2017 and has been updated.