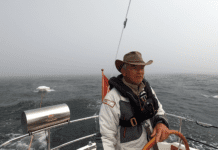

Photo courtesy of Hubert Cartier/NOAA

This month, Practical Sailor continues its look at US Sailings recent reports on three well-publicized sailing accidents last summer. Last month, we looked at US Sailings report on the Severn Sailing Association (SSA) accident involving the drowning death of 14-year-old Olivia Constants in Annapolis, Md. This month, well recap US Sailings investigation of the tragedy involving the light-displacement sloop WingNuts, which capsized in July 2011 during the Chicago Yacht Clubs Chicago to Mackinac race.

In the interest of full disclosure: Practical Sailor Technical Editor Ralph Naranjo served on the US Sailing panel that investigated the WingNuts accident. He reported on weather and boat design and was not directly involved in evaluating personal safety equipment, the focus of this report. The personal safety gear probe was handled by noted marine author John Rousmaniere and West Marines vice president of product development, Chuck Hawley, who also chaired the panel that produced the report. Because the accident involved West Marine-brand gear, Practical Sailor raised concerns about Hawleys involvement in an editorial in December 2011. Several readers, including Rousmaniere, commented on this topic in the Mailport section of the January and February 2012 issues. The full accident report can be found at http://about.ussailing.org/US_SAILING_Meetings/USS_Reports.htm.

Chicago-Mackinac Island Race

WingNuts, a Kiwi 35, was one of 345 boats participating in the 103rd Annual Chicago Yacht Club Race to Mackinac Island, covering approximately 333 miles. The boat, which had competed in prior Chicago-Mac races, was well crewed. Of the eight members aboard, several had crewed aboard WingNuts in past Chicago-Mac races. The skipper, 51-year-old Mark Morley, had been racing since his childhood and was well respected by fellow racers.

Visually, the 35-foot boat (length overall, LOA) stood out because of its extreme design, even among fellow competitors in the fast-light Sportboat Class. The boats beam was close to 14 feet due to its fold-out wings on either side, but the waterline beam was only 8 feet, 4 inches. The wings allowed the placement of crew ballast well to windward to increase the righting moment. Although there were flotation tanks in the wings, the design lacked the form stability you typically find in a modern wide-beam racing boat.

The accident occurred shortly before a change of watch at 11 p.m. on the races second night. According to the US Sailing report, WingNuts co-owner Peter Morley, 47, was steering the boat, while his brother, Mark, moved forward in the cockpit to the port (windward) side to look at the weather radar overlay on the chartplotter. Crew Suzanne Bickel, 40, was on the starboard (leeward) side, clipped to a centerline jackline in the cockpit, next to Stan Dent, 51. Stan, Peters brother-in-law, was clipped to the starboard jackline. Peters 15-year-old son, Stuart, and Stuarts 16-year-old cousin, C.J. Cummings, were on the port (windward) side, clipped to the port jackline. Two sailors were not wearing inflatable PFD/harnesses. John Dent, 50, Stans cousin, was down below; he was not wearing his PFD/harness. Crew Lee Purcell, 47, was wearing a West Marine harness over a Type III, foam-filled life vest. He used a modified sail tie to attach himself to the boat. With the addition of the two boys, the crew had realized too late that they did not have enough tethers for everyone.

Photo courtesy of Hubert Cartier/NOAA

Prior to the capsize, the crew had been watching an approaching line of thunderstorms and were tracking it on radar overlay on the chartplotter. The boat was sailing under a small, number 3 furling jib; the mainsail was furled and the boom was centered. Shortly before the boat capsized, Stan, who was captain of the new watch, recalls seeing a wall of white. Mark shouted, Roll the jib! and grabbed the furling line. He had furled the sail about halfway, according to the report, when the wind violently blew the boat over on its starboard side. Peter recalled sensing the boat going past 90 degrees and yelling, Its going over, everybody get clear of the boat.

The report says, Mark and Suzanne were thrown together to the end of their tethers onto the leeward wing, suffering serious injuries on the back of Marks head and Suzannes face . . . they very likely were unconscious before the boat settled upside down.

As the boat turned turtle, everyone except John, who was still down below, was connected to a jackline. The next harrowing moments, as the sailors tried to free themselves, are dramatically recounted in the report. Nobody saw Mark, although Stan, as he swam around the port stern, came upon both Suzanne and Peter. He tried desperately to free Suzanne from the underside of the boat, but could not reach her harness to free her. She was unresponsive to his tugs on her right arm. Stan then went to cut free Peter, who was being dragged under by his tether, which was secured to his harness with a cow-hitch. Stuart helped free C.J., who was struggling to keep his head up. Eventually, all of the surviving crew except Peter, who was too exhausted to climb, scrambled up the overturned hull.

The surviving crew were soon rescued by fellow race boat Sociable, led to the overturned hull by the sound of a whistle and a single light waved by one of the survivors, and then by other lights from the same area, including a bright spotlight shined in Sociables direction. Two SPOT Satellite Messenger beacons are also credited in the report with alerting family members and the Coast Guard.

Divers recovered the bodies of Suzanne and Mark the next day; their PFDs were inflated, and they were still tethered to the overturned boat.

Contributing Factors

The US Sailing report focused on four key elements that might have been factors in the accident: crew experience, weather, boat design, and safety equipment. Crew experience was quickly ruled out; nearly everyone aboard, except the two boys, had strong racing backgrounds. This was Marks sixth Chicago-Mac race.

The US Sailing panel also looked very closely at weather and how weather forecasting impacted the race. The intensity of the wind gust, possibly a microburst, that struck WingNuts was estimated at 50-plus knots. Several boats in the vicinity of WingNuts recorded strong gale-force winds with gusts in excess of 50 knots as the squall line passed. According to the US Sailing investigation, the severe line of thunderstorms that generated the strong winds was not unusual for that time of year, and it was predicted. Nevertheless, the panel found that many racers would have benefitted from better pre-race weather training.

Radical Design

The report attributes the primary cause of the accident to the boats radical design. On paper, WingNuts met all stability requirements for the Chicago-Mac race. The race required that all boats have an Offshore Racing Rule (ORR) handicap measurement certificate, a document that includes two measures of stability: Limit of Positive Stability (LPS) and the Stability Index (SI). However, after the accident, the US Sailing panel found that the ORR formulas did not adequately penalize the Kiwi 35s extreme flare, the difference between the waterline beam and the maximum beam. When the panel eliminated a fixed lower limit for the capsize increment-one of the factors used in the calculating stability index-WingNuts index of 100.7 plummeted to 74.4. No other boat in the race had the same drastic reduction in its stability index when the same math was applied. In addition, the panel noted that the Right Arm Curve (GZ Curve)-a graphic representation of the boats stability-revealed WingNuts to be just as stable inverted as it was right side up, sharply reducing any chance of recovery from a full capsize.

The US Sailing panel concluded that the prime contributing factor to the accident was the boats design, which, in its view, was not appropriate for a multi-day race in open water. It recommended that US Sailing redefine or recalculate the Stability Index so that it more accurately represents the boats ability to resist or recover from a knockdown or capsize.

In the wake of the US Sailing report, the Mackinac Race Committee moved to eliminate the stability measurement loophole that allowed boats like the Kiwi 35 to compete. US Sailing also eliminated the loophole in the stability formulas.

With regards to safety gear, the report finds that problems associated with auto-inflating PFD/harnesses or tethers were not linked to the fatalities. It concludes that such personal safety equipment did not endanger the crew of WingNuts and are desirable for the vast majority of situations.

A table accompanying the report lists the type of PFD/harness and tether that each crew was wearing, where they were tethered, and how they released themselves. The table appearing with this article indicates US Sailings original information (in blue), along with data filled in by Practical Sailors research (in red).

PS Analysis

The primary factor in the accident-as the panel rightly points out-was the Kiwi 35s radical design. When stability is calculated without a loophole that misrepresented the Kiwi 35s susceptibility to capsize, the boat clearly lies outside of the norm for the Chicago-Mac fleet. The US Sailing reports graphic representation of the boats stability, with no lower limit on the capsize increment, provides a stark illustration of this. (See adjacent graphic.)

US Sailing also handles the role of weather well. Instead of falling back on the excuse of a freak weather incident, the panel accurately points out that these sorts of violent squalls are not uncommon in that region during that time of year, so racers need to be prepared.

Where the report fails, in our view, is in the safety gear discussion. Of particular interest to Practical Sailor were comments on the clips and hooks used to connect the tether and harness, as well as findings on auto-inflating PFD/harnesses. In the last decade, Practical Sailor has carried out several different tests of PFD/harnesses and tethers and have found a number of problems, among them: tethers have snapped, snap-hooks have broken, auto-inflating harnesses have accidentally inflated, and quick-release snap-shackles have failed to open (see West Marine Tether Recall).

Quick Release

At the time of WingNuts capsize, all but one of the crew-John, who was down below-were still attached to the boat with some form of tether. The reports statements regarding tethers-five members of the eight-man crew were able to release themselves from the vessel and tethers that can be quickly unclipped from the harness under load did not endanger the crew of WingNuts-suggested to us that these quick releases generally worked well after the capsize.

However, PS found that only two crew were able to free themselves without resorting to using a knife or getting help from a fellow crewmember.

Of the seven crew in the water and attached to the boat after the capsize, only Mark, Suzanne and C.J. had tethers with quick-release snap-shackles that would qualify as capable of being quickly unclipped from the harness under load. C.J., wearing an auto-inflating life jacket and being pulled under by his tether, tried but could not release his quick-release shackle. He said the inflated tubes made it difficult for him to reach the snap-shackle. His cousin, Stuart, eventually pulled the quick-release lanyard and set C.J. free.

Of the four other crew tethered to the boat, two did not have any type of opening-hardware connecting the tether to the harness. Lees tether was tied to his harness. Peters tether was secured with a cow-hitch at the harness, with no means of release except by cutting it. In the ensuing chaos of the capsize, Stan was able to cut Peter free. Lee stated to police that he could easily untie his tether.

Two surviving crew had snap-hooks (as opposed to a quick-release snap-shackle) on their tethers.

Stan, trapped under the cockpit, unclipped his tether at the jackline, but the tether snagged when he tried to swim clear. He used his knife to cut himself free. He doesn’t recall attempting to open the snap-hook attached to his manual-inflating PFD/harness, which was not inflated when he cut himself free.

Stuart was the only sailor who released himself using tether-harness release hardware. He opened his snap hook before his PFD/harness was inflated. His tether was an old West Marine tether with snap hooks at each end; one was clipped into the D-rings on his West Marine auto-inflating PFD/harness.

The snap-hook type used by Stan and Stuart was allowed in previous Chicago-Mac races, but the 2012 Mackinac Safety Regulations specify quick-release snap-shackles that can be released under load, as recommended by the International Sailing Federation and US Sailing. Mark, Suzanne, and C.J. were the only WingNuts crew with this type of release.

Flotation

The US Sailing report findings state that there is no evidence that the buoyancy of the inflatable life jackets worn by the crew inhibited their ability to escape from the inverted cockpit. We found that no surviving crew member was trapped beneath the cockpit with an inflated PFD, so the suggestion that inflated PFDs were not a problem is unsubstantiated.

The two survivors briefly trapped in the air pocket under the hull-described as having between 4 and 18 inches of clearance and lifting and falling in six-foot seas-were Stan and John Dent. Neither were wearing auto-inflating PFD/harnesses, and their statements to police make it clear that they were glad they werent. John intentionally left his in the cabin, because he knew he didnt want it with me under the cockpit. The three survivors who were wearing auto-inflating vests-Stuart, C.J., and Peter-entered the water clear of the cockpit. Mark and Suzanne, found dead the next day still tethered to WingNuts with their PFDs inflated, were the only two sailors with auto-inflating PFDs who were trapped beneath the cockpit.

Medical Examiners Report

According to the US Sailings findings, the medical examiner lists head injuries as the cause of death. The medical examiners report, however, lists two causes: head injuries and drowning. (The US Sailing narrative of the accident does later refer to drowning.)

The US Sailing report promotes the theory that Mark and Suzanne very likely were unconscious before the boat settled upside down. However, according to Charlevoix County Sheriff W.D. Schneider, whose department conducted its own inquiry, whether the victims tried to free themselves in the water will never be known.

No autopsy was performed, but it was clear that both victims suffered head injuries. Suzanne had abrasions on her chin, cheek, and forehead, and a bruised right eye. Marks left temple and forehead were severely bruised, as was his left eye. The fact that Suzanne was unresponsive to Stans tugs on her right arm suggests she was unconscious by that time. Survivors point out that both victims carried knives, and that they could have cut themselves free if they had been conscious.

In our view, the US Sailing report should not discount the possibility that the tethers and/or inflated jackets may have inhibited Mark or Suzannes ability to escape. According to the sheriffs report, for a person trapped under a hull in a self-inflating PFD, the ability to escape is of serious concern. The sheriff also points out, another concern is the ability to be able to unhook the tether from the harness or PFD once the PFD is inflated.

Bottom line: We found that several of the US Sailing reports findings regarding safety gears performance were not supported by facts. The tethers were a problem for some survivors once the boat was capsized. The claim that PFD buoyancy did not impede any crew who were trapped under the cockpit is misleading. Contrary to what the report implies, the suggestion that Suzanne and Mark lost consciousness before they entered the water cannot be known.

Conclusion

In our opinion, the US Sailing panel should have offered a more balanced report on the sailors experiences with specific types of safety gear, and as soon as it became clear that the victims were wearing gear from West Marine, Hawley should have recused himself from the investigation.

In addition to US Sailings recommendations posted with this article, weve added some additional points:

Tether quick-release snap-shackles do not consistently release when the tether is under loads of greater than about 150 pounds. Far from perfect, they are the only quick-release option for now.

Accessing the tethers quick-release mechanism when hooked into inflated harness/PFDs can be extremely difficult.

When not in use, boat-end tether clips or clips on two-leg tethers should never be attached to the harness. Only a single quick-release snap-shackle or similar device should be connected to the harness.

Auto-inflating harnesses can prevent deaths due to the gasp reflex, in which a drowning victim reflexively ingests water, but they have shortcomings.

Know how to deflate your inflatable PFDs. Trying to escape from a sinking or capsized boat, reboarding a boat, or boarding a life raft in an inflated PFD can be extremely difficult.

A sharp knife should be kept handy at all times while underway.

Personal locator beacons (PLBs), whistles, and lights that are worn at all times can be valuable lifesavers.

We should not lose sight of the fact that the WingNuts crew struggled with equipment that has saved many lives and probably saved lives in the WingNuts incident. Our findings are not meant to suggest that this equipment is bad, or should not be used, just that we believe it can be improved.

Ultimately, the US Sailing report makes several well-reasoned recommendations for more research into stability standards, suggests important pre-race training, and calls for more research into tethers and harnesses. It explicitly recommends more training for releasing a PFD/harness while the bladder is inflated. On all of these counts, we wholeheartedly agree.

Next month, we will look at the sailing accident involving Rambler 100, a high-end racer that lost its keel and capsized while competing in the 2011 Rolex Fastnet Race.

Thank you, a very good report, agree with your comment regarding the conflict of interest, that taints the report