With so many conveniences aboard the modern cruising boat, it’s easy to forget that the bare essentials required to get us from here to there are so few—the hull, the rig, the sails, and the rudder. And with the rudder, of course we include the steering system that allows some control.

Unlike the hull, the rig and the sails, the steering system is often out of sight, tirelessly working beneath the cockpit sole or aft in a lazarette. Gears mesh, sheaves turn, cables push or pull, and inevitably they wear or begin to corrode.

Like many maintenance chores below deck on a small vessel, inspecting the steering system often requires us to squeeze into dark corners of the boat, where even if we do fit, the light is poor. Any flaws that might offer a hint of impending disaster can easily go unnoticed.

But inspect it we must. All it takes one corroded cotter pin, one loose screw, one frayed wire to begin the cascade of failures that can lead to disaster. It surprises to me how frequently I find mild steel components in a new boat’s steering systems, as if salt air never made its way below deck.

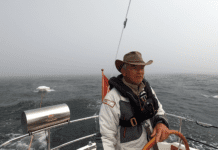

It is easy for the armchair sailor to talk of jury rigging a steering repair, or using sails or drag devices to steer in place of the rudder, but when you are far from safe harbor and near a lee shore or other some hazard, the sense of helplessness can be overwhelming. Sure, you made it through the storm that led to the failure, but what about the next one? Will your disabled boat be able to creep around the next cape or reef?

Losing steering has to be one of the most challenging situations to confront at sea, especially when you are tired. Although the boat is otherwise fit for sea, the inability to set a safe and comfortable course can prompt the most difficult decision. You need only do an internet search under the terms “sailboat abandoned at sea,” and you’ll find several sad accounts of sailors abandoning an otherwise perfectly good boat that had lost its steering.

Even my own cruising boat, the Atkin ketch Tosca—a tiller-steered boat with a barn-door rudder that seemed immune from harm—suffered her own brush with rudderlessness, when a loose set screw in the shaft coupling caused the prop to jam in the rudder when I put the boat in reverse. The incident occurred on the Miami River, so the consequence was merely embarrassing: we put our bowsprit into a bachelor pad (a story for another day). The helplessness I felt when I realized I’d lost all control made me vow it would never happen again.

Hopefully, this month’s article by Ralph Naranjo (see page 7), exploring the various types of steering gear—and their various pitfalls—will inspire each of us to take a close look at our own system and make sure we can avoid any failures, as well as be prepared with a plan in case this occurs