Alright, we know what some of you are thinking. “A Hinckley? In Practical Sailor?” For those of us with more utilitarian tastes, the “practical” nature of an elegant, floating example of Maine’s finest craftsmanship does seem elusive. But, in our book, a good boat deserves a good look, and this particular model makes some un-Hinckley-like detours worth sharing. Finally, when used boat prices are falling, you can bet the Hinckley’s of the world will be in a better position to recover their value when the market turns, making them—as far as used boats are concerned—a practical investment. Now is a very good time to dream.

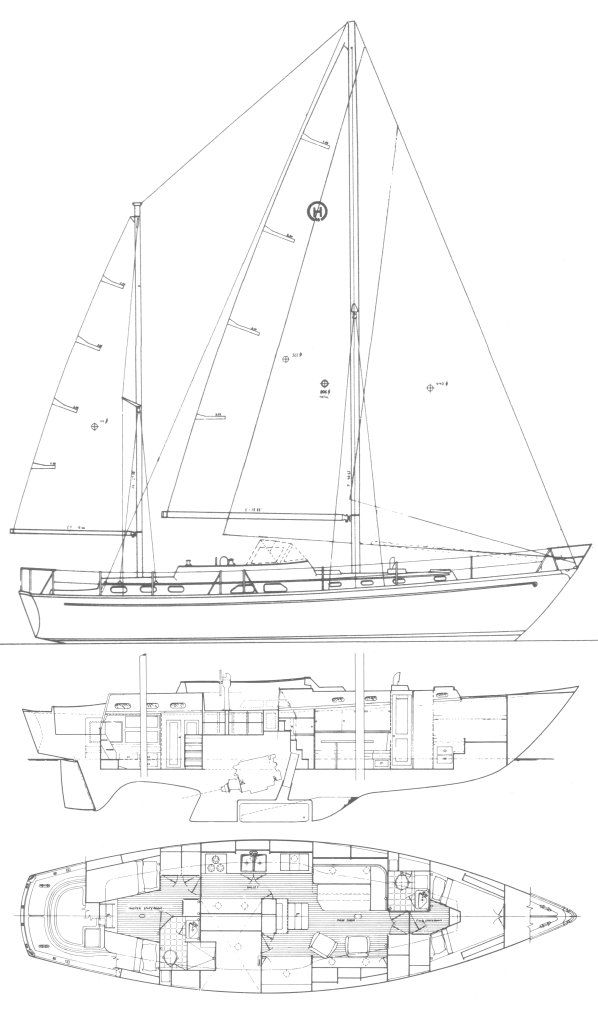

A proven builder of boats for others, Henry R. Hinckley envisioned the H49 as a comfortable cruiser for his own family. The big, beamy (for the era), shoal-draft centerboard ketch would prove to be a capable cruiser, at home in Maine’s cool waters or while meandering the near-tropical conditions of the Bahamas. And for those so inclined, the H49 also lived up to the demands of around-the-world voyaging. Between 1971 and 1976, 24 ketch and sloop versions of the sailboat were built, and today the fleet’s cruising accomplishments and owner satisfaction is hard to beat.

Built in the classic ritual of all early fiberglass Hinckley’s, the 49s sport a thick-as-a-plank solid glass hull; a massive inward-turning, mechanically fastened hull-to-deck joint; and an all-around heavy-duty set of scantlings that have stood the test of time.

In this boat review, we will address why it can make sense to buy a quality-built older vessel and why it’s essential to make sure that the boat’s attributes meet the needs of the present-day owner and crew.

BACKGROUND

The H49’s cult following is in part due to Henry R.’s vision and his willingness to step out of the mold when it came time to design the boat he wanted to cruise. It was 1970, and despite the company’s growing success in high-end production boatbuilding, he tacked away from the Hinckley trend of low freeboard, less roomy, and smaller payload-carrying sailboats symbolized by the Pilot 35, B40, and SW50. The existing fleet bridged the racer-daysailer-cruiser market, but the boats also excelled as fashion statements while swinging on yacht club moorings.

Altering the formula, Henry shed the runway-model mandate and allowed his design to take on a more usable hull volume, plus an un-Hinckley-like broadened stern that made room for a comfortable aft cabin. The H49’s center cockpit also ran contrary to Hinckley tradition, but some boatbuyers preferred the better visibility from the helm and the way a dodger and bimini top could be worked in to the equation. Even the mini owner’s cockpit aft of the cabin house—in spite of its questionable usefulness—earned praise.

Other significant design departures were the small sail plan and significant reduction in drive as well as heeling moment. Less sail area, combined with the boat’s primary role as a coastal cruiser, led the designer to call for only 8,000 pounds of ballast and a 500-pound centerboard. That is a very small amount of lead for a vessel displacing 38,000 pounds.

The very modest 22-percent ballast ratio negatively affects the vessel’s secondary righting moment, and its limit of positive stability is likely to be less than 110 degrees. Despite this ultimate stability shortfall, many of the H49s have made lengthy ocean passages, including a few voyages around the world. One of the mitigating factors is the H49’s inherent strength and rugged well-thought-out construction details, just as important as a vessel’s righting moment when it comes to contending with heavy weather at sea.

BIG-BOAT TRADEOFFS

Most boat reviews heavily weight a vessel’s ability to perform under sail in light-to-moderate conditions. Sea trials and the anatomy of how a vessel is built also take center-stage importance. We’ll follow that prescription in this review, but we’ll also look closely at long term live-aboard requirements and how a larger vessel can still be user-friendly to a short-handed crew.

The implications of tradeoffs, like the stability issue mentioned above, are important to recognize. And features of design, such as heavy displacement and limited sail area, shut the door to the H49 fitting the role of a performance cruiser with light-air capability. But this boat was designed to be an agile motorsailer with favorable ability under sail-once the breeze hits 14 knots or more.

Among the big pluses of the H49 are her shoal-draft cruiser capability and true long-term live-aboard characteristics. The smaller sail plan is easier to handle, and its comfortable motion underway includes a slow roll period—a feature linked to less ballast and a higher center of gravity.

Installing a bow thruster makes tight-quarters maneuvering a user-friendly experience. The 49 sports Hinckley’s trademark elegant and utilitarian rubstrake, a feature that takes some of the contact-sport trauma out of docking.

True to the Hinckley reputation, the H49 sports plenty of high-quality hardware, fasteners, and components—even in places that may never see the light of day. The stuffing box for the prop shaft, the rudder stock, and the gudgeons that attach the rudder to the massive skeg are the best silicon-bronze castings available. Details like the stem plate and chocks follow the Hinckley tradition of top-notch metallurgy and attention to detail.

Ground-tackle handling gear varies from boat to boat, but the foredeck has room enough for either a vertical or horizontal capstan windlass, and the deep forepeak area is spacious enough to keep the chain from castling.

CONSTRUCTION

In an era of higher-performance lightweight sailboats, many have forgotten the value of a thick-skinned non-cored hull like that of the Hinckley 49. Such hand layups were a blend of 24-ounce woven roving and 1.5-ounce chop strand mat. The latter added bulk and helped fill the “crimp” valleys formed in the warp/weft weave of the roving.

Early Isopthalic polyester resins easily wet out the material, and a dedicated work force armed with rollers and squeegees worked out the air bubbles. Thanks to such conscientious efforts, and the extra-thick hull laminate, blistering rarely ravaged these hulls, and when symptoms did occur, they could easily be repaired.

In addition to the overbuilt hull adding longevity, it also adds to peace of mind during accidents such as a grounding or when a heavy chunk of flotsam goes thud in the night.

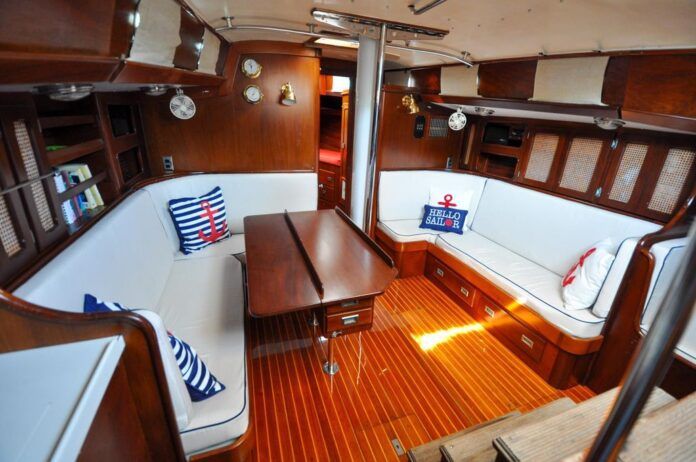

The H49s have “stick built” interiors with mahogany joinery bonded to the inner hull skin and finished in place rather than fashioned on the shop floor and secured to liners and pans. There’s a hand-built wooden boat ambiance to the interior. This stick-built approach also allows better access for interior modification, wire conduits, heat and air conditioning ducting, and other features of a comprehensive systems upgrade.

ACCOMMODATIONS

Belowdecks, the companionway ladder leads to the junction of the nav station, the galley, and the main saloon—each with enough space to eliminate any sense of claustrophobia. Despite the dark mahogany finish, the cabin has plenty of light thanks to an abundance of well-placed hatches and ports.

The L-shaped dinette with opposing settee/transom berth, shelves, and cupboards offer the right balance between open and functional space. Just as important is the fact that these accommodations work both in port and underway.

PS testers initially had some reservations about the in-line galley set up on the H49’s port side in the passage leading toward the aft cabin. But we found that there was plenty of working space, a well-gimbaled LPG stove, 9 cubic feet of fridge/freezer space, and deep double sinks—all great features that make it easier to cope with life at sea. The vessel’s high form stability and smaller sail area make extreme heeling angles less likely, and despite the fact that many chefs prefer a U-shaped, centerline galley, Hinckley’s approach worked just fine during our examination.

The aft-cabin layout is the antithesis of the contemporary trend toward cramped interior design, where a king-size mattress is wedged under the cockpit sole with only a few feet of headroom. The Hinckley 49 aft cabin has its own cabin trunk with full centerline standing headroom and comfortable twin berths port and starboard. An owner’s head with a freshwater shower resides just forward and to starboard of the cabin, and an aft companionway in the cabin opens out into the small stern “owner’s” cockpit mentioned earlier. There is storage galore in the cabin to handle the demands of long-term live-aboard life.

Forward of the mast is a classic twin-berth double cabin, an expanded version of what you might find squeezed into a 40-footer. With larger berths and extra cabinets and drawer space, the “V-berth” is very comfortable. A good-sized second head goes along with this forward cabin and hanging lockers fill in the space to starboard.

But the pièce de résistance for many cruisers is the real engine room access that’s provided by the numerous well-positioned doors and access panels. Henry R. saw the H49 as more motorsailer than racing sailboat, and he set aside plenty of room for the hefty Ford Lehman 6-cylinder 120-horsepower diesel to “breathe,” and to give those maintaining the engine enough room to work.

PERFORMANCE

Most of the 49s were rigged as ketches, but later retrofits of most included switch-overs to furling sails and power winches, which make sail handling even easier. A few boats in the line also were rigged as cutters with sprit-mounted headstays and furling inner forestay sails. Regardless of the sail configuration, the relatively short, single-spreader rig and heavy displacement hull make light-air sailing a lesson in patience.

Hinckley understood this drawback to his design well before the first boat was in the mold and wisely opted for a substantial diesel and a good-sized fuel tank.

In less than 10 knots of breeze, a 1,200- to 1,500-RPM motorsail delivers 7-knots-plus capability and can get the crew where they want to go in a relative hurry. The top-end cruising speed under power is around 9 knots, allowing the crew to keep up with trawlers or to efficiently stem a foul current. The crew intent on long distance passagemaking will find more regular stints of 12-knot winds and above, conditions that enable the well-balanced boat to romp along with a very manageable sail plan.

Despite the fact that few owners will be racing the H49, its worth looking at Performance Handicap Racing Fleet (PHRF) ratings for some perspective on how the boat performs compared to boats of a similar size and nature. The H49’s 150 PHRF (Northeast region) handicap is driven by weight and limited sail area, factors that stifle performance in 10 knots of breeze or less. The Island Packet 45 has a 126 PHRF rating while the bigger-rigged Passport 47 has a 114 handicap.

However, the 120-horsepower Ford Lehman diesel and 300-gallon fuel tank are the H49’s aces in the hole. It’s more than an auxiliary sailboat; in fact, when it comes to solving the light-air puzzle on this boat, a twist of the key trumps sock-snuffed spinnakers or furling gennakers every time.

THE CATCH

With its comfy accommodations and versatility as a motorsailer, the H49 is a great candidate for a live-aboard. But those considering the purchase of one must also see the boat from the other side of the coin.

Calling the H49 a varnish farm is by no means an overstatement, and those who love the rich amber hue of well-maintained teak on deck and the sumptuous glisten of varnished mahogany below won’t be disappointed. In addition to the coamings and toerails, there are grabrails, hatches, dorades, and plethora of bits and pieces on deck that represent a boatyard manager’s dream come true. Keeping all the brightwork gleaming is a time-consuming or wallet-lightening endeavor, but one with aesthetic rewards for the owners and onlookers.

Another challenge with the H49 is balancing the value of the asking price with what will be needed in the form of a systems upgrade. Some are approaching five decades of use, and most have gone through several major refits. Those considering an H49 should look closely at what a good surveyor has to say about hull and deck condition and also should pay heed to the condition of the engine, tanks, spars, rigging and electrical systems.

New sails and an array of modern electronics is nice to find on board, but we would much rather find a tired mainsail, an old Kenyon, and a blinking Raytheon depth sounder and know that the previous owner had sprung for a new engine, generator and fuel tank. This is a big vessel with room for systems galore, and with each comes a maintenance cycle and a need for power.

Those with cruising and live-aboard requirements that lean toward a bigger vessel but who have a budget on the south end of the six-figure range should look closely at the Hinckley 49. We noted brokerage listings with boats priced more dependent upon condition rather than the year the boat was built.

Market Scan Contact

1975 Hinckley 49 Private listing

$300,000 USD See Craigslist

New York City Craigslist

1973 Hinckley 49 East Coast Yacht Sales-Camden

$195,000 USD 207-263-0192

Annapolis, Maryland Yacht World

1972 Hinckley 53 WellFound Yachts

Priced to sell (305) 451-5385

Key Largo, Florida WellFound Yachts

1972 Hinckley 49 CC Ketch Superior Yachts

$299,000 USD (206) 378-1110

Washburn, Wisconsin Yacht World

CONCLUSION

Henry R. Hinckley was well ahead of his time. Today, Hood Yachts, Island Packet, Nordhaven, Bruckman, and a gamut of European builders are reintroducing motorsailers that switch-hit between power and sail. Some have big rigs, and others are as modestly canvassed as the H49.

The bottom line for boat buyers is to rank well ahead of time their boating priorities. And for those interested in a solid, capable and elegant floating home, who don’t mind (or prefer) powering in lighter conditions, but still want to sail when the breeze is up, the Hinckley 49 can be both a bargain and good investment in the long run.

| Hinckley 49 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sailboat Specifications | Courtesy: sailboatdata.com | |||||

| Hull Type: | Keel/Cbrd. | |||||

| Rigging Type: | Masthead Ketch | |||||

| LOA: | 49.00 ft / 14.94 m | |||||

| LWL: | 40.42 ft / 12.32 m | |||||

| S.A. (reported): | 922.00 ft² / 85.66 m² | |||||

| Beam: | 13.42 ft / 4.09 m | |||||

| Displacement: | 38,000.00 lb / 17,237 kg | |||||

| Ballast: | 8,000.00 lb / 3,629 kg | |||||

| Max Draft: | 10.00 ft / 3.05 m | |||||

| Min Draft: | 5.67 ft / 1.73 m | |||||

| Construction: | FG | |||||

| Ballast Type: | Lead | |||||

| First Built: | 1971 | |||||

| # Built: | 23 | |||||

| Builder: | Henry R. Hinckley & Co. (USA) | |||||

| Designer: | H. Hinckley | |||||

| Calculations and Ratios | ||||||

| S.A. / Displ.: | 13.11 | |||||

| Bal. / Displ.: | 21.05 | |||||

| Disp: / Len: | 256.89 | |||||

| Comfort Ratio: | 43.01 | |||||

| Capsize Screening Formula: | 1.60 | |||||

| S#: | 1.48 | |||||

| Hull Speed: | 8.52 kn | |||||

| Pounds/Inch Immersion: | 1,938.18 pounds/inch | |||||

| Rig and Sail Particulars | ||||||

| I: | 49.00 ft / 14.94 m | |||||

| J: | 18.80 ft / 5.73 m | |||||

| P: | 40.70 ft / 12.41 m | |||||

| E: | 15.83 ft / 4.82 m | |||||

| PY: | 27.38 ft / 8.35 m | |||||

| EY: | 10.20 ft / 3.11 m | |||||

| S.A. Fore: | 460.60 ft² / 42.79 m² | |||||

| S.A. Main: | 322.14 ft² / 29.93 m² | |||||

| S.A. Total (100% Fore + Main Triangles): | 782.74 ft² / 72.72 m² | |||||

| S.A./Displ. (calc.): | 11.13 | |||||

| Est. Forestay Length: | 52.48 ft / 16.00 m | |||||