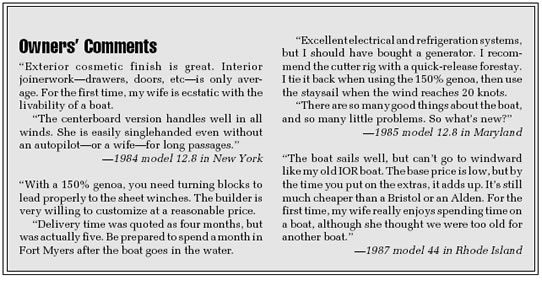

The Brewer 12.8 and the Brewer 44 are developments of the Whitby 42, a cruising boat from the board of Ted Brewer. Brewer is one of the great modern cruising boat designers. His boats are well-mannered, attractive and practical.

According to the designer, the Brewer 12.8 and Brewer 44 use the same basic hull and deck as the Whitby 42, a boat that was designed in 1971. Hull changes to the Whitby 42 were made by cutting out the long keel and attached rudder, replacing them with a more modern short keel and skeg-mounted rudder. This eliminated a lot of wetted surface, improving the light-air performance.

To improve windward performance, a high aspect ratio centerboard extends through the bottom of the 12.8s shallow keel. Since the board is not ballasted, it does not affect stability, but can be used when reaching to shift the center of lateral resistance.

The Brewer 44 is the same boat as the 12.8, with the stern extended slightly, increasing the size of the aft stateroom. This has the fortunate side effect of making the boat slightly narrower aft and reducing the size of the transom.

Both the Brewer 12.8 and the Brewer 44 are semi custom boats: you don’t go down and buy one from a dealer, you have one built. Eliminating a dealer network does away with commissions of approximately 20%-a significant saving to the customer on a boat this size.

Since the Brewer 44 is slightly larger-more boat for the buck-has a better aft cabin, and doesn’t cost a lot more to build, it has replaced the Brewer 12.8 as the standard model. You can still get a 12.8 on special order if you want a 42′ boat. Wed opt for the bigger boat because its better looking and has a much better aft cabin. Otherwise, the boats are virtually identical.

Absolutely the only advantage the 12.8 has over the 44 is that it is easier to lower a dinghy stowed in davits down the vertical transom of the 12.8. On the reverse transom of the 44, the dinghy tends to hang up as you drop it.

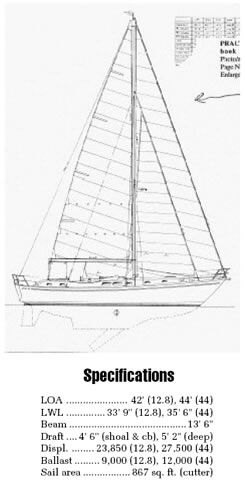

Its easy to get a little confused reading the specifications for the three boats. The beam of the 12.8 and the 44 is listed as 13′ 6″, while the Whitby 42 is 13′ wide. According to the designer, the difference probably comes from including the molded-in guardrails of the Brewer 12.8 and Brewer 44, since no change was made to the hull width.

Both the 12.8 and the 44 have 4′ 6″ standard draft, yet the 44 has from 2,000 to 3,000 pounds more ballast, from 2,650 to 3,650 pounds more displacement (depending on which ad you read), and a waterline from 1′ 3″ to 1′ 9″ longer. According to the builder, the 44 started out with 11,000 pounds of ballast, but that has gradually increased to almost 12,000 pounds.

Since there is no actual change in the keel depth or position in the two boats, it is reasonable to assume that the increasingly heavier 44 actually draws more than the advertised 4′ 6″. The extra displacement of the 44 probably translates into a base draft of about 4′ 9″. In practice, both the 12.8 and the 44 will draw even more in cruising trim, since owners of these boats frequently load them up with heavy items such as generators and bigger-than standard batteries.

The 12.8 and the Brewer 44 are built by Fort Myers Yacht and Shipbuilding. The yard has built 40 12.8s, and 24 of the 44′ version have been sold. The yard also built 33 Whitby 42s under license from the Canadian builder.

The 12.8 and the 44 were conceived as good performing, long distance livaboard cruisers. The members of the original syndicate which commissioned the Brewer 12.8 were experienced racing and cruising yachtsmen who wanted the livability and layout of the Whitby 42, coupled with a higher performance hull and rig configuration.

Hull And Deck

There is nothing fancy about the construction of the Brewer 12.8. The hull is a conventional layup of mat and roving, with balsa core from just below the waterline up to just below the sheer.

The hull-to-deck joint is formed by a glass hull bulwark with an inward-turning flange. The outward-turning bulwark flange of the deck molding overlaps this, and the hull and deck are bolted and bedded together. This is a good, solid joint. It is capped with teak.

A fiberglass rubbing strake is molded into the hull just below the sheer. Its a toss-up between a molded fiberglass rubbing strake and a bolted-on wooden one. Certainly maintenance will be easier with the fiberglass strake, but a wooden strake might absorb a little more impact without damage to the hull, and would probably be easier to repair or replace. In any case, a rubbing strake is a good idea on a boat that may well be laid alongside primitive docks in far-off places to load fuel or water.

Some of the construction details strike us as a little light for a serious cruising boat of this displacement. The shroud chainplates, for example, are 1/4″ stainless steel. If this were our own boat, and we were planning serious offshore cruising, wed want those chain plates to be 3/8″ material.

Likewise, rig specifications call for 9/32″ wire for shrouds and backstay, plus a 5/16″ headstay. Wed rather see at least 5/16″ shrouds, plus a 3/8″ headstay. The specified wire sizes are adequate, but we prefer a little more margin in an offshore cruiser. The lighter wire saves some weight and windage aloft, and a little money.

Some of the construction details are very good. Lifeline stanchions are 29″ tall, spaced closely together, and properly backed with aluminum plates. Some finishing details on the early 12.8 we sailed, on the other hand, were less satisfactory. For example, rather than using solid teak molding in the door frames, the Brewer 12.8 had glued-on veneer edging. Likewise, aft of the settee backs there are access hatches to storage areas. These access hatches are merely cutouts in the plywood, and the edges were not even sanded smooth before painting.

The Brewer 44 we looked at was a totally different animal in finish detail. Doorways have solid teak edge moldings; detailing is much better throughout. Where the early 12.8 rates only average production boat in the detailing category, the 44 detailing is very good production boat in quality. When we looked at the 12.8, we figured it needed another 200 hours of detailing to match its potential. The 44 is just about there.

Rig

The standard rig of both the 12.8 and the 44 is a well proportioned, modern, high aspect ratio cutter. The mainsail area of 368 square feet is about the maximum size conventional mainsail that a retired couple would want to handle. If the boat is going to be a longterm retirement home, wed consider going to a roller-reefing mainsail such as the Hood Stoway or Metalmast Reefaway. This type of decision should be made when the boat is built, since a retrofit is an expensive proposition involving replacement of the spar.

The mast is by Isomat, with Lewmar halyard winches mounted on the spar. The rig is stepped through to the keel.

Engine And Mechanical Systems

Standard engine for the Brewer 44 is a 62 hp Perkins 4-154. A larger 85 hp Perkins is optional. Either engine is more than adequate power for the boat. We prefer the smaller engine for its better fuel economy, but if you want a real motorsailer, the bigger engine is a reasonable choice. The Brewer 12.8 used the 62 hp Lehman Ford engine.

With the standard 135 gallons of fuel and the smaller engine, range under power is about 700 miles. This is just about what youd want in a big cruising boat that sails well.

Plumbing and wiring systems are good, but the standard batteries are too small for the boat. Although the standard equipment list is reasonably thorough, a lot of equipment you’d want for serious cruising is optional. The basics such as hot and cold pressure water, propane for cooking, fuel tank selection system and fuel filters are standard, and well executed.

Handling Under Power

The Brewer 12.8 with the Lehman diesel motors comfortably at 6 knots at about 1700 rpm. This is a very economical cruising speed. Both of the Perkins engines are capable of pushing the boat faster, but when you’re cruising, fuel economy is more important than how quickly you get there. The boats have a lot of windage. A major criticism of the Whitby 42 was that it was difficult to handle at low speeds when docking, particularly in a crosswind. Both the 12.8 and the 44, with their more cutaway underbodies, maneuver substantially better. This is still a big boat, and it will not spin on a dime like a smaller boat.

One change that would dramatically improve both speed under sail and handling under power would be to install a feathering prop such as the Maxprop instead of the standard solid prop. The 44 we looked at had a three-bladed Maxprop, and the owner wouldn’t have it any other way. A feathering prop gives full thrust in reverse-unlike either fixed or folding props-yet offers little more resistance under sail than a folding prop.

Midships cockpits with engine rooms below can be noisier both on decks and belowdecks. These boats have fairly good sound insulation in the engine room; you know the engine is running, but it’s not obtrusive.

Handling Under Sail

The Brewer 12.8 sails as well as you’d want for a cruising boat. The boat is extremely well balanced. In about 12 knots of true wind-16 knots or so over the deck-we could trim the sails for upwind sailing, then walk away from the helm without even setting the wheel brake. In smooth water, the boat tracks and holds course well.

In puffier conditions, the boat tends to round up sharply when close reaching with the board fully extended. This is not much of a surprise, since most beamy boats do this.

With a large-diameter steering wheel and mechanical pull-pull steering, response and feel are excellent.

The boom on the 12.8 we sailed was very high off the deck. We ended up climbing onto one of the halyard winches to hook up the main halyard. This is a disadvantage, particularly if the crew is older and less agile.

Furling the main is also complicated by the high boom. You can reach the boom for furling at the mast and atop the aft cabin, but its difficult to do it over the center cockpit. Likewise, with the big dodger up, you can’t get to the boom over the main companionway. The boom is probably placed this high to clear a Bimini top, but it sure makes it a chore to set and furl the mainsail.

In contrast, the boom of the new 44 we examined was just enough lower to make hooking up the halyard and furling the mainsail a straightforward proposition.

Most of the standard winches for the boat are marginal in size, particularly if the boat is to be used for retirement sailing. Standard genoa sheet winches, for example, are Lewmar 52 self-tailers. These are approximately equivalent to the Barient self-tailing electric 28s that were on our test boat. Larger Lewmar primaries are optional, and should be chosen. Wed pass up the optional electric primaries at over $6,000, unless its the only way you can trim the sails.

The main halyard on the boat we sailed-one of the original eight Brewer 12.8s-had a poor lead: from a block at the base of the mast, through a deck mounted cheek block, through the dodger coaming, to a stopper and winch atop the cabin just forward of the cockpit. The turning block at the base of the mast was too high, allowing the halyard to chafe at several points, particularly on the cheek block. In fact, we could barely crank up the main using the Lewmar 30 halyard winch. This is easily corrected, but it was annoying to see the same poor lead on the brand new 44 we examined. In fact, the owner of the 44 had ordered a larger than standard main halyard winch to overcome the friction in the system.

Our test boat was rigged as a cutter. Staysail sheet winches are self-tailing Lewmar 30s mounted on the forward end of molded winch islands just outboard of the cockpit coamings. With a large cockpit dodger in place, it is difficult to impossible to use these winches: they’re actually hidden outside the dodger, and the dodger side curtains have to be unclipped to trim the staysail.

The primary headsail sheet winches are also awkward to use. The winch handle swings through the lifelines. This is a function of the wide, midships cockpit; sail handling has been compromised to create cockpit room.

There are properly through-bolted aluminum genoa tracks mounted atop the bulwarks. On our test 12.8, there was also a shorter inboard genoa track, which could be used to advantage going to windward, since the main shroud chainplates are set inboard of the rail. In practice, few of these boats will be equipped with a deck-sweeping genoa, so the inboard track is probably superfluous.

The 12.8 we sailed had large Schaefer turning blocks aft for improving genoa sheet leads to winches. However, these blocks were mounted almost flat on their welded winch islands. Since the winch is higher than the turning block, the lead from the block to the winch is not fair, which can cause chafe on the sheet and increased friction in the system. The blocks should be angled upward slightly to correct this, which could be done with shims or with a slight redesign of the mounting weldments.

On the Brewer 44, aft turning blocks are not standard. With a very high-cut genoa whose lead was very far aft, you could end up with an awkward sheet angle at the winch unless turning blocks are installed. This is a disadvantage of sail handling from a cockpit in the middle of the boat.

A full-width mainsheet traveler is mounted atop the aft cabin. Our 12.8 used a Schaefer traveler, while the 44 has a Lewmar unit. Controls for the Lewmar traveler cars are at the back end of the aft cabin. You have to climb out of the cockpit to adjust them. The original Schaefer traveler has car adjusters just aft of the helmsman, with stoppers and a Lewmar 30 winch. We’re at a loss to explain why a good setup was traded for a bad one.

The mainsail is trimmed by a Lewmar 30 self- tailer mounted atop the aft cabin, reasonably accessible to either helmsman or crew. This winch is powerful enough for a mainsail this size.

A double-headsail ketch rig with bowsprit is an option that will set you back about $7,000 by the time you buy the mast, sail and fancy bowsprit. Frankly, if you want a ketch rig because its easier to handle on a boat this size, you’d be better off spending that seven grand on a Stoway cutter rig, huge self-tailing sheet winches all around, and roller furling on both the genoa and staysail. It would probably be easier to handle than the ketch, and you’d keep the better performance of the single-masted rig.

Despite relatively shoal draft, the Brewer 12.8 is reasonably stiff. With full main and 150% genoa, the boat heels about 20 with 18 knots of breeze over the deck. With the optional deeper keel she would be a little stiffer, but the keel/centerboard combination is probably slightly faster on most points of sail, if a little tippier in heavy air.

We think the extra ballast in the Brewer 44 will make her an even better performer than the Brewer 12.8 in winds of over about 15 knots. Although the extra displacement and wetted surface will slow the boat slightly in very light winds, the standard rig is big enough to keep the boat moving in winds as light as most people care to sail in. When it’s too light, you can always turn on the engine. Most cruisers simply aren’t interested in squeezing out every ounce of performance in light air.

There are actually three different underwater configurations for the Brewer 44: a shoal fin keel; the same shoal keel with a high aspect ratio centerboard; and a slightly deeper-but still relatively shallow- fin keel.

The centerboard has become optional-it was originally standard on the 12.8-because a lot of people simply never bothered to use it. The boat sails fine without it; it just goes sideways a little more.

On Deck

Sail handling limitations aside, the cockpit is just about ideal for a cruising sailboat. You can comfortably seat eight in the cockpit for idle hours at anchor.

An Edson wheel steerer dominates the cockpit. It has custom boxes with electrical switches for anchor windlass, autopilot-you can practically run the boat from here. We’re a little concerned about the proximity of all this wiring to the steering compass, however. When having the compass swung, be sure to operate every piece of electrical equipment on the steering console to make sure that nothing affects the compass.

A high molded-in breakwater makes installing a full-width dodger fairly easy. A good cockpit dodger is essential on a center cockpit boat. Without a dodger, a center cockpit is a wet place to live sailing or motoring to windward in a blow. Both of the dodgers we looked at, however, blocked access to the staysail sheet winches.

Side decks are very narrow due to the wide cabin trunk. This is a definite compromise. The shroud chainplates come down right in the middle of the side decks, yet there isn’t room to walk outboard of the shrouds. Instead, you must step up and over the cabin.

Although its a $1,500 option, most owners will choose the stainless steel stub bowsprit with twin anchor rollers. The 12.8 we sailed had a CQR plow in the starboard roller, and a Danforth stowed sideways in the port roller. It was not the best arrangement. The 44 we examined had plows in both rollers, and they fit, although it is a tight squeeze.

A lot of these boats are equipped with custom davits for carrying a dinghy off the stern. They’re a good idea, since theres little deck space for stowing a dinghy aboard.

At the same time, carrying a dinghy in davits offshore can be a risky proposition, particularly in a following sea. The skipper of one 12.8 had the dinghy fill with water during a rough passage- someone forgot to take the plug out-and was afraid the entire arrangement of davits and dinghy was going to be lost. For passage making, wed probably bring the inflatable aboard and break it down for stowage, as awkward as that may seem.

Fuel fills are located in the waterways at just about the low point in the sheer. Water fills are in the waterways forward. As we found, you have to be careful if you’re taking on fuel and water at the same time. We overfilled the water tank, sending water straight toward the open fuel fill. Quick hands-not ours-got the cap back on the fuel fill before water could pour into the tank. It wouldn’t be a bad idea to raise the fuel fill about an inch off the deck on a pad to reduce the chances of this happening.

Belowdecks

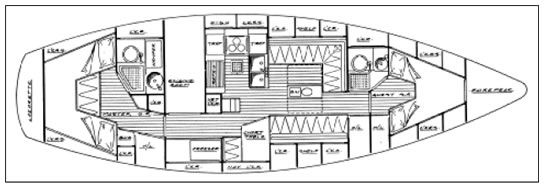

Some of the compromises in sail handling and deck layout have been made for the sake of the interior. The wide deckhouse that makes for narrow side decks creates a huge interior volume, and the space is used very well.

Because the forward cabin is pushed well into the eyes of the boat, the forepeak anchor locker is small. You can lead the anchor chain aft to the locker under the berths in the forward cabin, which has the advantage of moving a lot of weight further back in the boat, where it has less effect on pitching moment.

The forward cabin has V-berths, with an insert to form a double. The berths are quite narrow at the foot, and are only comfortably long for someone under 6′ tall. Outboard of the berths there are storage lockers, and there are drawers below.

Ventilation in the forward cabin at anchor is provided by a large Lewmar hatch and Beckson opening ports. Offshore ventilation consists of a cowl vent in a Dorade box.

You can enter the forward head from either the main cabin or the forward cabin, since there are two doors. Unfortunately, the door to the forward cabin wipes out the space that would otherwise be used as the head dresser. Instead, you get a little sink with not much space for laying out the essentials of your toilette.

The forward door also means that the head sink is pushed fairly far outboard. With the boat heeled over on starboard tack, seawater backs up through it. One boat we looked at had a big wooden plug to stick in the drain, while the other owner had added a shutoff valve to the drain line just below the sink.

Ironically, the small head dresser is quite low, and could easily have been raised up another 4″ or so. This wouldn’t eliminate the problem, but the boat could heel over a little more before you’d have to do something about it.

Both the forward and aft heads use inexpensive, bottom-of-the-line water closets. Our experience is that cheap heads work fine for daysailing and coastal cruising, but are a curse for the serious livaboard cruiser. Wed rather see a Wilcox-Crittenden Imperial or Skipper on a serious cruising boat.

A solar-powered vent overhead provides exhaust ventilation, but we think in addition that every head should have an opening overhead hatch. A cowl vent in a Dorade box would also be a good idea. It’s impossible to have too much ventilation in a head.

The main cabin has a straight settee to starboard, an L-shaped settee to port. You can also have a pair of armchairs on the starboard side instead of the settee, but we see no advantage to this. The L-shaped settee has a drop-in section to convert it to a double, so that you can have three double berths on the boat, if you’re masochistic enough to want to cruise with three couples. The good thing is that the boat does contain three separate living spaces, with direct

access from each of the spaces both to the deck and to a head compartment. Thats a tricky thing to do, and Ted Brewer has pulled it off as well as you can.

Aluminum water tanks holding 200 gallons are located in the bilge under the main cabin.

There is good locker space outboard of the settees in place of the more commonly-seen pilot berths that usually become useless catch-alls. One locker is designed as a large booze locker. When you think about the imbibing habits of a lot of sailors, this makes a lot more sense than stuffing one bottle here, another over there.

Ventilation in the main cabin is good for in port, less good for offshore. There are four opening ports in the main cabin. The standard ports are plastic, which we think is not an acceptable material for an offshore cruiser of this type. Stainless steel opening ports are an option costing $1,890. This buys you very good cast-frame opening ports, which we think should really be standard on a boat of this caliber.

There are also two aluminum-framed hatches over the main cabin. The hatches currently used are single-opening Lewmar hatches with extruded frames. The older 12.8 we sailed had double-opening Atkins & Hoyle cast hatches. A double-opening hatch allows you to open the hatch forward in port for maximum air flow, aft when sailing to keep water from getting below. We wish they had stuck with the more expensive cast hatches.

Two cowl vents in Dorade boxes are provided for sailing ventilation. Like the cowl vents on a lot of boats, the down take pipes into the cabin of the Brewer boats are improperly proportioned: they should never be smaller than the nominal pipe diameter of the vent itself.

The galley has undergone a lot of minor changes since the first boats in the Brewer 12.8 series were built. The early boat we examined had sinks that were too small, water fixtures that were too low relative to the sinks, drawers that were difficult to operate, and fiddles without corner clean outs. The 44 we examined had changed all of these things.

One thing has not changed. Between the sinks and the stove, there is a large dry well for storage. This is about the size and shape of a large grocery shopping cart. You wouldn’t want to have to dig to the bottom of a grocery cart for the cereal and crackers every time you wanted to use them, but thats pretty much what you have to do with this well. It should at least be divided with sliding shelves to make it easier to use.

At the aft end of the galley, there is a large refrigerator and freezer mounted athwartships. It is well insulated, and has a well-gasketed top.

Theres another big opening hatch over the galley, and it is properly placed behind the dodger breakwater, where it can serve as an exhaust vent in any conditions-as long as the dodger is up.

Standard stove is a three-burner propane stove with oven-just what youd want.

A big chart table is opposite the galley. While it has good storage for navigation books, there is no coherent arrangement for the mounting of the array of electronics that you find on the typical modern cruising boat. Since these boats are built on a semicustom basis, you could probably have the nav station modified to suit your particular electronics. These boats were designed before the contemporary electronics explosion, and some details have not been upgraded to reflect the state of the art.

Aft of the nav station, there is a passageway with stooping headroom to the aft cabin. On the starboard side of the passage, there is a huge workbench with chart storage and tool storage below. This is a great way to use this space, rather than trying to throw in another berth.

On the older boat we looked at, this same space was filled with a huge freezer and battery storage- an advantage of semi-custom flexibility. The big electrical panel is located over the workbench: out of the way, yet reasonably accessible. Opposite the work area, under the cockpit, is a real engine room. Theres room for the main engine, an optional generator, fuel filtration system, hot water storage tank, and batteries. Although you have to climb over the engine to check the batteries, everything is reasonably accessible. A real engine room is a rarity in a boat this size, and is only practical with the center cockpit configuration.

The aft cabin of the 12.8 has two quarterberths which can be joined by a drop-in section to create a large thwartships double. The extra 2′ in the stern of the 44 makes it possible to have a big permanent fore and aft double berth. If you want, you can still get the two berth configuration.

A separate companionway at the forward end of the aft cabin gives access to the cockpit without going through the passageway. This companionway has a slatted drop board, and since it faces forward, it is vulnerable to spray. For offshore sailing, it should be secured with a tight-fitting canvas cover. In port, it will provide good ventilation at the expense of some privacy. There is also another aluminum-framed hatch over this cabin. It suffers from the same limitations as the hatches over the main cabin.

You can get a sit-down shower stall in the aft head, or have a more conventional arrangement using the entire head as the shower compartment. A sit-down shower may be easier to clean, but you give up a lot of head dresser space to get it.

There is excellent locker space throughout the boat, including three hanging lockers and a foul weather gear locker. Instead of packing in extra berths, the designer and builder have chosen to limit the number of berths and maximize storage. It was a wise choice.

With the exception of the under-cockpit passage, headroom is well over 6′ throughout.

Conclusions

Since the Brewer 44 is a lineal descendant of the Whitby 42 and Brewer 12.8, a lot of the shortcomings of those boats have been ironed out over the years. Finishing details have gradually improved, and have generally kept pace with the boatbuilding industry trend toward better detailing.

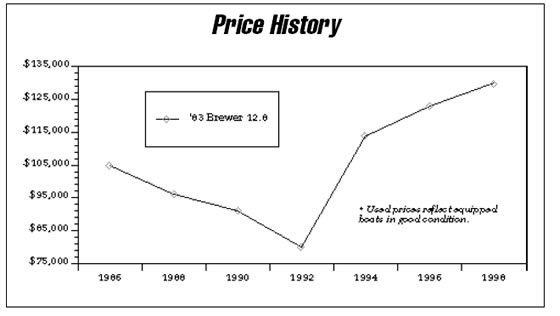

At first glance, the sail away price of just under $160,000 seems like a misprint. That price includes main and genoa, Hood roller furling on the headsail, propane, refrigeration, basic electronics and pumps. Theres also a long options list. The kicker is that a lot of the things on the options list should be standard on a high-quality cruising boat. For example, the bigger primary sheet winches that we think are required cost an extra $1,800. A teak and holly cabin sole is another thousand; two tone decks (rather than plain white) add $670. Lightning grounding costs $720, an anchor platform $1,500.

Although the boat was designed as a cutter, staysail rigging, winches, and the sail itself add $2,600.

Standard batteries total only 225 amp hours capacity. For batteries the right size, add $400. For metal ports rather than plastic, shell out almost $1,900. Even the centerboard in a boat that was designed as a keel/center boarder adds $2,600 to the sail away price.

With the options that we think are really essentials, the sail away price jumps by about $15,000.

What do you get for $175,000? You get a well designed, good-sailing, well-built ocean cruising home, a retirement cottage for every romantic port in the world. The boats are not as well detailed or equipped as higher-priced boats such as Aldens, Hinckleys, and Little Harbors. But they’re good, solid values, and they’ll take you to the same places as more expensive boats. In this day and age, thats not a bad recommendation.