The early Cal boats were built by Jensen Marine in the old ’70s Mecca of fiberglass boatbuilders that was Costa Mesa, California. Columbia and Islander were there, too. For a decade they dominated the burgeoning market for relatively inexpensive, “maintenance-free” boats.

Jack Jensen and designer Bill Lapworth were at the forefront of this revolution, beginning their long association in 1958 with the introduction in 1959 of the Cal 24. The famous Cal 40 sprang from the family tree in 1963, winning the SORC the next. Despite such notoriety as a racer, the Cal 40 and many others in the line were described as good, all-around family boats with modern divided underbodies, relatively light weight, and hence they had an emphasis on performance.

The Cal 46 was introduced in 1967. One reader said he thinks about 10 were built. For several years it was called the Cal Cruising 46. The Cal 2-46, with a redesigned deck, cockpit and interior layout, succeeded it from 1973 until 1976. The Cal 3-46, virtually the same as the 2-46 except for some minor interior changes, was built in 1977 and 1978.

A 1972 profile of Lapworth in Yachting magazine said, “A prototype of the Cal Cruising 46, Hale Field’s Fram, embodying able sailing characteristics with motorsailer cruising comfort, made a circumnavigation of North America (with the help of a train ride from Michigan to the Pacific Northwest).”

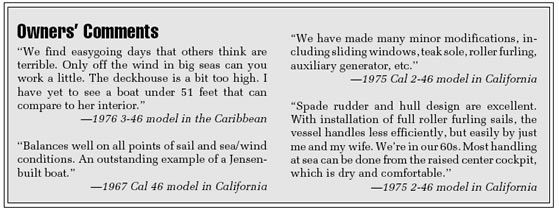

David and Beverly Feiges, owners of a Cal 3-46, wrote to us at length about the boat, and in citing the devotion of Cal 46 owners, noted that many have circumnavigated. They added that both Lapworth and Jensen chose the boat as their personal retirement yachts for extended blue-water cruising.

The early Cal boats were built at a time when a handful of big California builders dominated the business. Cal, Columbia (including Coronado), and Islander offered boats from 20 to more than 50 feet. The largest Cal was the 48, modeled more after the highly successful 40. Like some large builders today, such as Beneteau and Hunter, Cal produced two distinct lines—one for racing and short-term cruising, and another for more hard-core cruising. In 1972, Columbia countered the Cal 46 with its Columbia 45 motor sailer, but by most counts it wasn’t as successful, nor as pretty.

Today, the Cal 46 stands as a boat that in many ways was ahead of its time, combining as it did a daringly different layout with 270-degree visibility from the deckhouse, a spade rudder and long cruising keel. That they are still revered and sought after comes as no surprise.

The Design

Lapworth certainly knew how to draw a fast hull. Even prior to the fiberglass revolution, he was convinced that light displacement was the way to go. His Nalu II won the Transpac in 1959 and his various Lclass boats also did well around that time. The Cal 40, as mentioned, won the 1964 SORC.

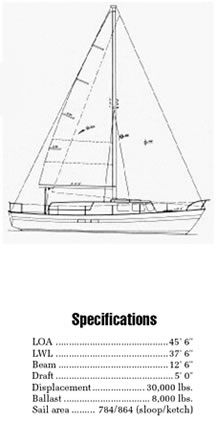

When it came to designing the ultimate cruising boat, Lapworth wasn’t about to settle for a slug. The Cal 46 has a displacement/length ratio of 250, which is considered moderate even today. When in 1973 Robert Perry designed the Valiant 40 with a D/L ratio of 260, many critics said it was too light for offshore work. After numerous, safe circumnavigations, the critics were proven wrong. Of course the Cal 46 is a big boat and when carrying a full load of fuel, water and provisions for cruising, its actual D/L ratio will be higher.

The boat has moderate overhangs by today’s standards, though in the 1960s it probably didn’t seem so. The spoon bow and carefully proportioned transom balance well. And there is some nice sheer to elevate the bow and keep it drier in bad weather. The deckhouse of the original 46 had large windows and the smallish cockpit was immediately aft of the mast. The coachroof stepped down about midship to the long, windowless cabin trunk, giving it a somewhat awkward appearance.

In the 2-46, the cockpit was pushed aft, the deckhouse windows decreased in size, and windows added to the cabin trunk for a much more handsome and balanced profile.

A sloop rig was the only option until 1973, when a ketch rig was made available. We don’t know how many of each were sold, but to our eye, the ketch seems more appropriate to the boat. For cruising, the extra stick enables the crew to sail with “jib and jigger” in high winds, and to fly a mizzen staysail in very light air. Neither rig has a lot of sail area, however. The short rig was mandated by the relatively shoal draft and high center of gravity. It was assumed, correctly, that most owners would find the beefy 85-hp. Perkins diesel the perfect antitdote to doldrums and drifters.

One of the more unusual features of the Cal 46 is its large spade rudder. Lapworth wanted to retain some performance features and apparently a keelhung rudder was anathema to his creed. The keel is quite long, though cut away significantly in the forefoot. It terminates just behind the cabin trunk, leaving space between it and the spade rudder for the propeller, which in the original 46 exits the deadwood horizontally for top efficiency. The Cal 2-46 relocates the engine closer to midships. Both drive the boat at its hull speed of about 8.5 knots with a cruising range of 1,200 miles.

The spade rudder gives the boat better control in tight maneuvering situations than a keel-hung rudder, especially since the keel is so long. The drawback

is the potential to snag lines on both the rudder and propeller. Addressing the question, the Feiges’ wrote: “It does have a spade rudder, which many people would call a fault in a cruising boat, but considering the advantages, and considering the damaged rudders of all kinds we have seen in boat yards, we’ll take our chances with our big beautiful spade.”

Draft is shoal at five feet. Clearly this boat isn’t going to climb away from a lee shore like an eightfoot draft fin keel racer, but as cruising is its priority, this was a trade-off Lapworth was willing to make. Even the shallow waters of the Florida Keys and Bahama banks won’t pose a problem for the Cal 46. And if you need to get to windward in a hurry? Crank up the iron jenny!

Nevertheless, spade rudders do require extra caution, especially in areas where fish nets and lobster pots are prevalent. Indeed, floating lines and logs are a menace worldwide, and the smart skipper will have some plan in mind for the eventuality of cutting free lines or other obstructions.

Construction

The Cal 46, like most early Cal boats, was hand-laid of solid fiberglass using cloth and woven roving. An early brochure states that the hull was engineered for

“maximum impact strength,” using “compressive strength materials on the outside” and “tensile strength materials on the inside.”

The lead ballast was precast in a mold, then lowered into the fiberglass keel cavity and glassed over. The wood bulkheads and structural furniture were fiberglassed to the hull. According to the company’s literature, this occurred before removing the hull from the mold, which is highly desirable. Removing the hull before it is fully supported, as some builders do, encourages the possibility of the hull deforming and making the fitting of the deck sloppy. The joint was “bonded together to form a double-thick seam” and “concealed by a decorative rubber or teak rail on the outside, and rendered invisible on the inside by filling, taping, sanding, and painting.” The sealant used was 3M 5200 and the joint was through-bolted with 1/4-inch machine screws.

The deck, according to Feiges, was cored with plywood, which structurally is a good material for this application. It is, however, much heavier than end-grain balsa and much more susceptible to farreaching rot from water leaking through deck fasteners. Interestingly, we have no reports of problems with the plywood. But, if we owned a boat with plywood-cored decks, we’d be certain that all throughdeck fasteners were periodically recaulked.

Interior joinerwork is Burmese teak. Overhead panels were covered with vinyl. The sole of some models was plywood supported by 2 x 2s and aluminum angles, with teak and holly over. On other boats, it appears, the soles were fiberglass with carpeting.

The large windows on all models (though their size were progressively reduced after the original 46), are a cause for concern. Most owners mentioned it in completing our Owner’s Questionnaire. Not only did they seem weak, but leaked as well. Most owners said they had replaced them with stronger materials or permanently covered them. At the least, some provision for attaching storm shutters should be made.

One owner said the black iron fuel tanks rotted out at 15 years. A 2-46 brochure says the two fuel tanks (totaling 135 gallons) are “10 gauge steel.” Water tanks, at least in later models, are stainless steel.

Overall, owners rate the construction of the Cal 46 as excellent. While the smaller Cals may have been regarded as budget boats, we have repeatedly observed that the larger boats in a company’s line are frequently built to higher standards. This appears to be the case with the Cal 46. At the same time, remember that this was a production boat with precut interior components, so don’t expect custom quality joinerwork and finish work.

Accommodations

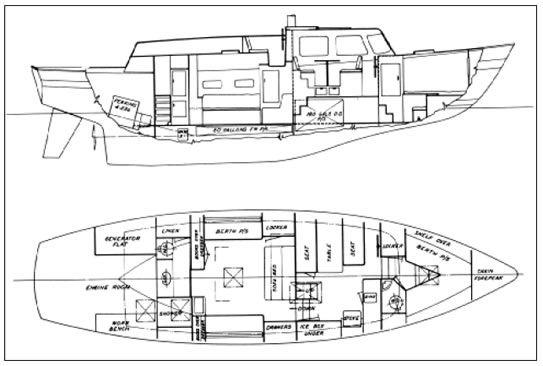

The original Cal 46 featured V-berths forward with its own head compartment, a raised deckhouse with dinette and galley, and a large “living room” aft with settees and a sofa bed. Aft of it is a large head with shower and access to the engine room, which had room for a workbench and generator set. In this configuration, the engine was coupled to a V-drive. Owners of all 46s are unanimous in their praise for the large engine room and its standing headroom. As one owner wrote, when her husband is fixing something on the workbench, “he, and the mess, is not in my hair.”

In the 2-46, with its longer deckhouse, two layouts were offered: one with an L-shaped dinette and one with an athwartship dinette with chart table forward of it. Both have sideboard galleys to starboard. The forward and aft cabins were identical, the latter with a double berth and head to port and a settee and hanging locker to starboard. The great appeal of the raised deckhouse is the ability to see through the windows while seated—no need to stand up every time you hear a noise!

An owner of a 3-46 wrote that it doesn’t have as locker and a separate shower stall. It also has a vanity, which she notes contains “a very capacious vegetable bin.”

Headroom in the 3-46 is a bit less, and the windows are a bit smaller.

The galley was moved into the passageway aft, making it smaller but more secure. She wrote, “We can hand food directly up into the cockpit through our port located above the sink. The saloon, without the galley, looks huge. There is plenty of storage space, and the largest chart table I’ve ever seen. At

sea, we run a heavy line from the companionway grabrail to the mast to the grabrail on the forward bulkhead, which has always allowed us to move around down below securely.” This is an interesting point, as many people don’t consider the liability of a large cabin at sea. If one must move from one point to another without benefit of a handhold, there is the danger of being thrown and injured. The safety line is a simple solution, though it won’t be as secure a handhold as a solid wood or metal rail throughbolted to a bulkhead.

The center-cockpit layout of the 46 was unusual in the late 1960s and early 1970s. By providing a stateroom at each end of the boat, two couples can cruise in privacy, leaving the dinette “up” all of the time. In a pinch, it could sleep extra crew.

An attraction of the 46 is that neither Lapworth nor Jensen tried to squeeze too much into the hull, leaving plenty of room for stowage and working, which is exactly what a couple or family needs when venturing far from home.

On deck, the cockpit is quite elevated and dry. roomy an aft cabin, but does have a larger hanging

Consequently, the cabin is tall; some may find it less pleasing to the eye than a lower-profile structure. But that would require higher freeboard, which might impair sailing performance. It may be helpful to install steps somewhere to make it easier to climb from the deck to the coachroof.

The side decks are not as wide as one might expect on a 46-footer, but remember that this design has just 12′ 6″ beam. And, as is usually the case, the designer wanted to maximize space below. Stepping around the shrouds can be a nuisance, but at least you have a handhold.

The cockpit seats are long enough to sleep on and the backrests are tall.

Performance

As one would expect of a boat with a short rig and shallow keel, sailing performance is not grand prix. The hull, however, is easily driven and the long

waterline helps achieve good speeds, especially when the wind is up. Several owners said light-air performance was less than stellar, but then one must remember this boat is part motor sailer, with a large diesel for such exigencies.

On the plus side, the rig fits under the East Coast’s Intracoastal Waterway fixed bridges. And, for those venturing to the latitudes of balmy tradewinds, which routinely blow at 20 miles per hour and more, a smaller rig is more easily handled, while still providing sufficient power to reach hull speed. Because it is a bit underrigged, one owner said the boat can carry full sails up to 25 knots of wind.

Most owners rate balance as superb. Several say the boat is a bit tender and that early reefing is a requisite of comfortable passage-making.

Performance under power is good. The Perkins 4-236 diesel is an excellent engine. The reduction gear is 3:1. The standard propeller was a 26-inch, threeblade that gives good power and control. Dragging it around under sail, however, is another matter. A good feathering propeller, such as a Max-Prop, would perceptibly increase sailing speeds as well as improve handling in reverse.

The Feigeses said their 3-46 came with two cutless bearings, counter to Lapworth’s drawings. One, they said, was impossible to lubricate or replace. So they removed one and installed instead a pillow block bearing to support the long shaft.

Motor sailers, as critics are wont to say, are neither beast nor fowl, representing either the best of both worlds, or the worst. The Cal 46 represents about a 70/30 split between sail and power. For a blue-watercruising boat, that isn’t bad. It sails decently on most points, and has the big diesel necessary not only for long periods of motoring, but also to run all of the convenience items important to long-term comfort at sea, such as refrigeration, inverter, desalinator and electric windlass. Equally important, there’s space in the engine room to install all of these goodies.

The original Cal 46 came with a Warner V-drive, which adds expense and complications. We’d prefer the direct drive of the 2-46 and 3-46.

Conclusion

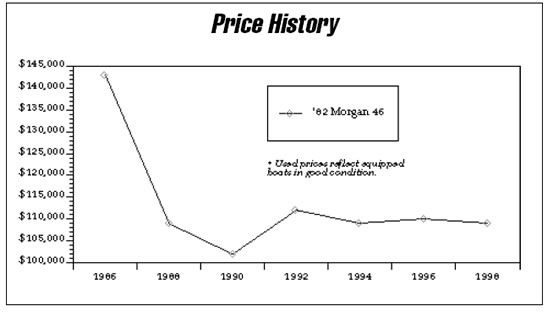

The Cal 46 is a big boat that’s sized right for longdistance cruising. It appears that most owners have been devoted to their vessels, and a prospective buyer can only hope that they have maintained them with equal diligence and effort.

Presumably, most of the early bugs have been resolved by now. According to owners, those bugs include large, leaky windows, wooden spreaders, black iron fuel tanks and other items of lesser significance.

The problem, if you’re interested, is finding one. Though more than 100 were built, they don’t often appear on the market. We’d look for a 2-46 or 3-46, preferring their deck and interior to the original 46. We also like the ketch rig better than the sloop on this design.

great article! most informative I’ve ever read on this sailboat!

great article! thx!

Thank you i found one and was looking forbinformation and i came to the right place its a cal46 and this really seald the deal fore

We Cruised and lived aboard a 1974 2-46, galley up. (By far the best layout). I have sailed, taught sailing as a US Sailing cruising instructor for one of the largest sailing schools in the US.

So have cruised many boats. Have owned 5 serious cruising boats. I say this as my judgment comes with extensive experience: I will say it simply, i love this boat. All boats are a set of compromises. This is the best set that I have found for live aboard cruising. We made 200 mile days (dragging that 26” prop) so it didn’t slow us down nearly as much as you would think. Sure, a quality feathering prop would be nice but not necessary. We crossed oceans with this. A WALK IN engine room! With work bench, drill press, vice, generator, watermaker large tool chest. Almost all equipment in the engine room NOT in your lockers. Nearly 17 feet of galley space!! She handled so well that she could sail down wind in a gale with minimal steering effort. She pointed reasonable well and yes, had some leeway. Under power, she motored as well as a trawler that I owned. Easily punching dead up wind on the infamous “Baja bash” sails furled and smack into 8 foot plus steep seas 25-30 on the nose making in excess of 5 kts. And what’s not to like with 270 gal of diesel!

Yes, a yacht way ahead of its time!