When a restless 40-year-old advertising executive with a background in one-design sailing (1970 World’s Sunfish Champion) went shopping for a cruising boat some years ago, he could not find one that made him happy. Conventional cruisers he found poor performers, needlessly difficult to sail shorthanded with their big headsails and complicated rigs, and with hull forms that demand auxiliary power any time the wind is forward of abeam.

It was in 1972 that this sailor, Garry Hoyt, set about developing an alternative. His alternative was the original Freedom 40. Discarding conventions one by one, he came up with a long-waterline, quasi-traditional hull form and a wishbone cat-ketch rig.

Then, to prove he had something, he took his prototype to Antigua Race Week and decisively out-performed the cruising boats with which he had been so unhappy. Granted, his talents as a sailor were considerably better than those of his competition and granted, his prototype without an engine had no propeller or aperture drag; nevertheless his concept gained a qualified validity.

In the intervening years Hoyt refined his rig and developed a whole line of boats: a 21, 25, 28, 39 (express and pilothouse models), and the 44. The Freedom 33 is no longer in production, having been replaced in the line by the 32, which is a single masted “cat sloop” with a self-tacking jib and gun mount spinnaker. More rig innovation.

Hoyt’s natural ingenuity produced the innovative boats, basic good luck led him to Ev Pearson of Tillotson-Pearson when he went looking for a builder, and his background in advertising let him create attention-getting explanations of his concept. His one notable weakness has been in marketing; until recently he tried with little success to bring potential buyers to the boat rather than putting together a dealer network that takes the boat to the public.

The US builder, Tillotson-Pearson, has been one of the most successful low-profile boatbuilders, putting together such popular boats as the J-Boat line and the Etchells 22 one-design. The firm has been a leader in the development of balsa coring for hull structure and carbon fiber for light, stiff laminates.

Unlike the situation with more conventional craft, selling the sailing public on the concept behind the Freedoms is a stiff challenge. The rig in particular is unfamiliar to most cruising sailors and for the concept to gain acceptance they need to be educated. Not only must they be convinced that the stayless masts, wishbone booms, and wrap-around sails are durable, they must be literally taught how to use them advantageously, For this reason reception to the idea has been mixed, and the appeal of the Freedom has been to sailors outside of the mainstream.

Construction

Basic construction of the Freedom 33 hull and deck is, in our opinion, among the best in the production boat building industry. From our observation as a result of examining boats both finished and under construction, we can detect no serious cost cutting or scrimping in the way of materials or techniques.

The Freedom 33 (as with other boats in the Freedom line) has a balsa-cored hull and deck. There are advantages to this type of construction—hull rigidity, thermal and acoustical insulation, reduction in hull weight—that we believe recommends it for hull structure provided it is properly engineered. In the case of the Freedom 33, we believe it is.

Lead ballast, 3,800 lbs, is cast in wedge-shaped pieces and fiberglassed into the bilge. The aluminum fuel tank (25 gallons) is also deep in the bilge. The centerboard, a combination of lead and fiberglass, is a hefty 1,200 lbs, also contributing to stability. The centerboard is the product of perhaps the most thoughtful design and engineering on the boat. It is pivoted in a channel, eliminating the need for a pin that breaches the hull.

Hoyt, with his eye firmly on performance, adopted an idea of designer Jay Parris for a centerboard configuration having a triangular profile and a constant chord. The design permits a centerboard with a shape that gives lift at any angle and, more importantly in reducing drag, a centerboard that fits its slot closely.

If the centerboard is not the most extensively engineered feature of the Freedom 33, then the spars are. Initially the Freedom 33 had two-part aluminum tubular masts that were heavy, reducing stability and increasing pitching moment. To help cure this weakness, Tillotson-Pearson undertook a research program into building one-piece spars using a carbon-fiber laminate.

The result is an approximately 30% saving in weight and considerably stiffer spars. The saving translated itself into markedly better performance, so much so that we suggest any buyer considering one of the increasing number of boats available with stayless spars should look into spar weight and stiffness.

Additional construction details of note on the Freedom 33 include a hull-to-deck joint through-fastened with 5/16″ stainless steel bolts and bonded with 3M 5200 adhesive sealant, a technique we recommend. Bulkheads are tabbed to the inside fiberglass skin, leaving the core intact to prevent hard spots from showing up on the topsides. The interior joinerwork, fetchingly of oak, ash, and spruce, is done to a high quality; our only serious reservation is discussed below.

Performance

Our evaluation of the performance of the Freedom 33 is in part the product of having spent a week sailing aboard the boat during Antigua Race Week. For comparison with that experience on the prototype, we recently sailed a production version, as well.

For those sailors used to masthead headsails and conventional mainsails with their sheeting, reefing, and halyard systems, the rig of the Freedom 33 does require some re-education. Initially one has the impression that the boat is under-rigged and that the sailplan is inefficient. That impression is, however, deceptive. The boat does have speed and liveliness that exceeds that of most out-and-out cruising boats of her size and in many conditions can rival the performance of the many so-called racer-cruisers or “performance cruisers.”

The mainsail and mizzen are efficient in that almost all their area forms an effective airfoil. The wishbone boom permits a longer luff than a conventional boom and does not interfere with the draft at the foot. The wishbone does create windage, though. Draft control is easier with a wishbone boom through either outhaul tension (the Freedom 33 mizzen) or adjustment of the effective length of the wishbone (the mainsail). Similarly the wrap-around sails are more efficient aerodynamically than sails set on a mast track or groove which are in part blanketed by the spar section. Given the greater diameter of stayless spars versus conventional spars, the wrap-around system is important in this type of rig.

For performance, proper sail shape, adjustment, and trim are as vital for this rig as for more conventional rigs. There are still some aspects of the Freedom rig about which we have reservations but from our experience we believe the Freedom line has come closer to perfecting the system than any of its rivals boasting similar rigs. Incidentally, Ulmer Sails (in particular Ulmer sailmaker Bob Adams), has worked hard to develop Freedom sail shape plus reefing and trimming systems and we therefore urge buyers to order the sails offered as “factory installed options” rather than trying to find another sailmaker who will have to go through the extensive design exercise needed to provide suitable sails.

The Freedom 33 is stiffer (and, we think, foot-forfoot, faster) than her sisters in the Freedom line. Her sailplan gives optimum performance in a mid-range of wind strengths, say 10 to 15 knots. In winds below 10 knots, especially to windward in any chop, the stubby hull, with a centerboard and plenty of wetted surface, is sluggish. In fact, no Freedom is as lively as we would wish in lighter winds, a factor to consider in such areas as Chesapeake Bay and Puget Sound. For such conditions we strongly recommend at least one mizzen staysail. Moreover, although we are not sold on poleless spinnakers (i.e., Flashers) for conventionally rigged cruising boats, we think they are superb as a mizzen spinnaker on a boat like a Freedom 33.

The wishbone booms and stayless masts combine to make the Freedom a delightful boat to sail with the wind from astern. The absence of shrouds lets the mainsail (and boom) swing forward of thwartships, encouraging her to sail wing and wing with the wind as much as 25 degrees or so off the quarter. Moreover, the sail stays out to windward in light winds without a preventer. Nor does it need a vang; the angle of the wishbone boom off the mast eliminates any tendency for the boom to lift. On a run almost any sailor accustomed to wrestling with blanketed or poled out headsails, cringing as his mainsail chafes on shrouds, and paranoid over the threat of accidentally jibing, will have to appreciate the Freedom rig.

Closewindedness is a relative term but a major attraction of the better modern designs. The Freedom 33 is not closewinded, as much as a result of her hull shape as her rig. However, she does not give away anything upwind to boats with shallow hull forms and long keels. Boat for boat she will sail by Morgan 41s, Irwin 44s, CSY 44s, Westsails, and their ilk.

The Freedom rig uses a slab or jiffy reefing system. Moreover, instead of the reefed portion gathering above the boom as with conventional sailplans the excess material gathers at the wishbone in aerodynamically messy folds. It is just not a rig that lends itself to simple, uncluttered reefing and we think finding combinations of reduced sail using staysails would be a better solution than trying to reef main and mizzen. Yet the present rig seems to have proven itself in offshore sailing. Several boats have made long passages without difficulty and weathered severe storms at sea with no breakdowns or crises. In fact, we sailed a Freedom 33 that a few days before had beat her way up Long Island sound in an easterly gale with gusts as high as 60 knots.

The sails are two-ply loosely connected at the leech. Furling is easy; the sail gathers into a basket formed of shock cord stretched across the wishbone. More shock cord across the top keeps the sail secured The convenience of this system, obvious as it may be, is one of the major recommendations of the rig, doing away with the onerous chores of conventional mainsail furling or headsail folding and bagging.

In all, we have been favorably impressed with the performance of a boat that experience and instinct tells us should be poor. The wrap-around sails take getting used to, but the more we played with them, the more effective they seemed to be.

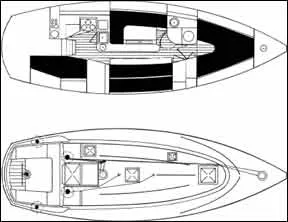

Deck Layout

Other than to handle ground tackle or docking lines, there is no reason why anyone has to leave the cockpit of a Freedom 33 under sail. All halyards, sheets, outhauls, reefing pennants, and the centerboard pennant lead aft to the cockpit where they are handled by a pair of self-tailing winches (Barient 23s) and an array of sheet stoppers. Moreover, the cockpit is short enough so that anyone handling these lines can also keep one hand close to the steering wheel, a boon for shorthanded or singlehanded sailing.

The cockpit seating is deep and the coamings are unobstructed perches on the Freedom 33. Best of all, the cockpit space is entirely usable. In fact, because the mizzen traveler is mounted aft, the Freedom 33 is a distinct rarity among production boats—a boat in which the traveler does not threaten to squash one’s legs or the mainsheet garrote the crew. The feature alone makes the cockpit of the Freedom noteworthy.

The steering wheel on a pedestal is mounted well aft, the helmsman standing (or sitting on a fold-up seat) on a teak grate under which, uncommonly accessible, is the steering cable and quadrant for the outboard rudder. The grate also serves as the cockpit drain with scuppers through the transom, a most effective arrangement for quickly draining a flooded cockpit. A sliding door at the after end of the cockpit houses propane fuel bottles.

The decks and house top are uncluttered sundecks and lounging platforms. Sailors used to gingerly stepping around a conventional deck may feel disoriented—missing are chainplates and shrouds, headsail sheets and blocks, and a spinnaker pole.

The anchor sits in an optional fiberglass bowsprit. Man-sized chocks on either side of the bow and amidships are integrally fitted into the teak toerail.

Interior

Garry Hoyt’s forte as a designer is clearly in his ability to develop performance. It has not been in his ability to design an interior. The Freedom 40 originally appeared with a midships cockpit and an interior so broken into segments as to be a disaster. The public understandably could not accept an accommodation plan in a 40-footer that was best suited for a chummy young couple (that to go with a rig that already took a vivid imagination to comprehend). Marketplace pressure dictated an alternative version with an aft cockpit and more versatile layout and the present Freedom 40 is a more successful product.

Similarly the Freedom 33 was first designed with an aft cabin that reduced cockpit space and a main cabin that succumbed to, rather than accommodated itself to, the centerboard trunk dividing it. The present production version does away with the aft cabin, locates the galley conventionally at the base of the companionway, tucks a dinette (convertible to a double berth) to port of the trunk, and has a settee berth to starboard. The result is a main cabin laid out much like other production boats of comparable proportions.

By having her waterline stretched out to virtually the overall length of the boat, the 33 has exceptional roominess for her modest length on deck. Moreover, with her mast stepped close to the stem, her hull fullness has to be carried well forward to support the weight. The forward cabin with its V-berth is the beneficiary. Farther aft the roominess is deceptive, however, because the main cabin is broken up by a 5′ long, waist high centerboard trunk running down the middle and the mizzen mast rising at the after end of it.

Had Hoyt not had his eye so fixed on performance, he might have opted for a longer, narrower centerboard permitting a lower trunk that could be located where it would intrude little if at all into the main cabin. As it is, the centerboard does offer minimum drag, does not “thunk” annoyingly in the trunk, and is rugged. It also needs a trunk that makes casual conversation awkward and it makes the dinette a cul-de-sac, leaving the person on the inside no convenient way to get out.

The aesthetic impression created by the interior joinerwork is among the best we have had about any production boat. All the wood below—and there is plenty—is a combination of oak, ash, and spruce (plus the teak and holly cabin sole). We have long been critical of interior decor relying on dark woods such as teak and mahogany. The warmth and illusion of spaciousness imparted by these light colored woods will appeal to many sailors. It certainly does to us.

There is a place for teak below. Grab rails, companionway treads, the framing around hatches, and the trim in the head—all areas liable to wear and getting wet—would be better in teak than in woods like ash and oak which are subject to staining. Moreover, oak is less dimensionally stable than teak, so moisture may eventually affect the structure as well as the finish.

We have some further observations about the interior. The comfortably wide quarterberth to starboard has little overhead foot room. The pilot berth to starboard is accessible only to a person shorter than 4′ and weighing less than 40 lbs; it is either a luxuriously cushioned shelf or a berth for an agile ship’s cat. Both the chart table and the clever dinette table need removable fiddles, and the hinges on the chart table lid would be better recessed.

And we have some incidental compliments. The stowage capacity of the Freedom 33 is by far the best we have seen in a boat of this size. In particular, the huge galley drywell, incorporating a sliding section for seldom used items, is nonpareil. The engine (Yanmar 3GM diesel) under the companionway is well above average in accessibility. The forward cabin can be completely closed off from the rest of the boat, including the head, by its own door.

The Freedom 33 thus offers an intriguing dichotomy—impressive and innovative decor and layout offset to a disturbing extent by drawbacks that may justifiably turn off many buyers and give owners things they will “have to live with.”

Conclusions

The Freedom 33 is an interesting boat. She is, however, not a conventional boat and the concept behind her rig takes getting used to, especially for someone born and raised in the tradition of headsails, standing rigging, mainsails that ride on tracks, hulls with overhangs and aesthetic proportions, and other quaint qualities.