The Pearson 303, introduced in 1983, is a fairly typical example of the kind of work Pearson was doing in the mid-1980s, continuing until its sale in 1991 to Aqua Buoy, which has yet to resume production. During 1983, Pearson built 12 different models, ranging from the durable 22-ft. 6-in. Ensign to the Pearson 530, the largest boat the company ever built. The long-standing 35 centerboarder and 365 ketch had been dropped the year before, and the mainstays of the fleet were the 323 and 424. Only the 30-ft. Flyer departed from the company’s commitment to cruiser/racers—the unfortunate appellation given to just about any boxy boat with a fin keel.

Pearson was decidedly more into the family coastal cruiser than serious racing, though its boats were commonly club raced under PHRF.

The Pearson 303, and later the 34, 36, 37 and 39 seemed to be nearly the same boat drawn to different lengths. Indeed, in 1991, all of the above models, except the 303 (terminated in 1986), were in production at the same time. There was a bland sameness to them. Not only in terms of the standard hull and deck colors, non-skid pattern, window treatments and interior finish, but in their lines as well.

One would suppose that designer Bill Shaw believed the formula to be successful, and for a time it probably was. Nevertheless, we suspect it also may have accounted for the company’s eventual demise. Time and again it has been said that larger boatbuilders, because they end up competing with their own previously-sold boats, must continually introduce new models. Example: You want to buy a Pearson 36, and are tempted to buy new. But a three-year-old model sells for less and is better equipped. You conclude that buying new is bad business. The dealer, sensing you are on the fence, tells you the company is about to introduce the Pearson 37, a much bigger and better boat with all sorts of improvements. So you take the hook and buy a new 37. But the phenomenon perpetuates itself, and because each new model requires expensive tooling, the company is making nowhere near the money it appears to be.

In their defense, Shaw and Pearson over the years designed and built a number of very interesting boats that were atypical of the rest of the line. The centerboard Pearson 40 and one-design Flyer come to mind. And though Pearson sold quite a few of each by any other builder’s standard, these departure designs never were accepted as well as the company’s family cruiser/racers. It seems the company was consumed in a vortex spun of its own successful sameness.

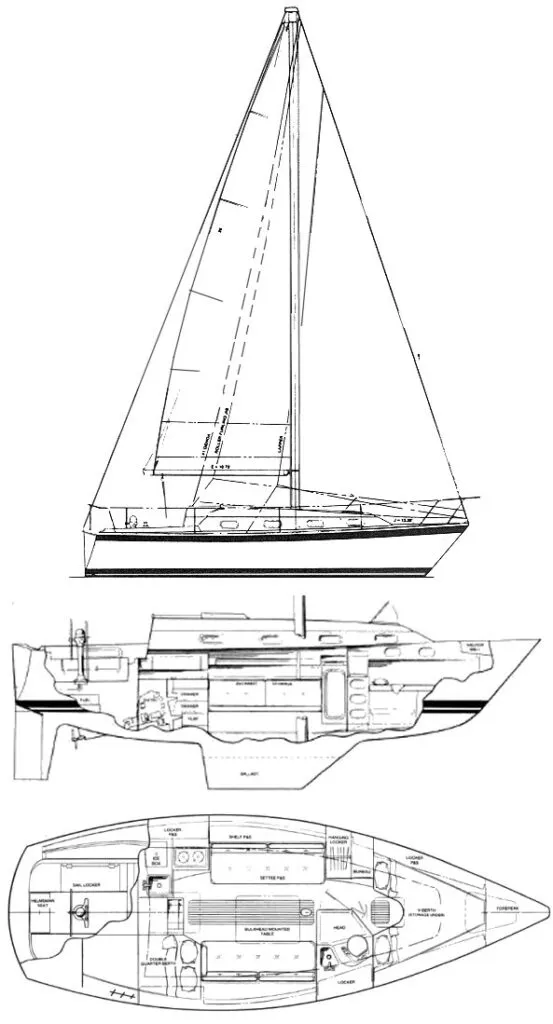

DESIGN

A quick look at the numbers shows that the Pearson 303 is a conservative design, moderate in every respect. Its displacement/length ratio is 274, and its sail area/displacement ratio is 15.6. These figures suggest a boat that is easily handled and with adequate volume for stowing cruising supplies. They also suggest a boat that is not particularly fast, corroborated by owner comments that are discussed under “Performance.”

The typical cruiser/racer will have a fairly shoal keel, as does the 303, which draws just 4 ft. 4 in. This is great for cruising the Chesapeake Bay’s back rivers, Florida Bay and the Bahamas, but unnecessarily shallow for just about anywhere else. A deep keel would improve windward performance noticeably.

The 303’s length/beam ratio (2.77 using LOA) is quite low. This gives the boat a lot of room inside, and helps provide initial stability so the boat won’t feel tender. At the same time, it is not the best proportion for ultimate stability or ease of handling in severe conditions. US Sailing’s glossary of terms in its IMS Profile booklet, says values range from “2.5 (short, wide) to 5.0 (long, narrow). High length/beam ratios mean lower wave making for a given displacement/length ratio and better controllability for given ratios for sail area/displacement and sail area/wetted surface.”

Unlike many later Pearsons, the 303 does have a skeg-mounted rudder, which tends to decrease then stalling angle, and, mounted far aft as it is, the skeg also adds a bit to lateral plane, which should help directional stability. Skegs also permit an added bearing support to the rudder, and may help protect the rudder in a collision with an underwater object.

Our conclusion is that the Pearson 303 is a big 30-footer, intended for safe coastal cruising. She admirably succeeds in doing what she was designed to do. The only risk accrues to those who mistake her for something she is not—an offshore, passage-making boat.

Pearson 303

Sailboat Specifications Courtesy: sailboatdata.com

Hull Type: Fin with rudder on skeg

Rigging Type: Masthead Sloop

LOA: 30.29 ft / 9.23 m

LWL: 25.37 ft / 7.73 m

S.A. (reported): 459.00 ft² / 42.64 m²

Beam: 10.92 ft / 3.33 m

Displacement: 10,100.00 lb / 4,581 kg

Ballast: 3,500.00 lb / 1,588 kg

Max Draft: 4.33 ft / 1.32 m

Construction: FRP w/balsa core bottom/solid topsides

Ballast Type: Lead

First Built: 1983

Last Built: 1986

Builder: Pearson Yachts (USA)

Designer: William Shaw

Auxiliary Power/ Tanks

Make: Yanmar

Model: 2GMF

Type: Diesel

HP: 13

Fuel: 22 gals / 83 L

Accomodations

Water: 40 gals / 151 L

Headroom: 6.25 ft / 1.91 m

Sailboat Calculations

S.A. / Displ.: 15.77

Bal. / Displ.: 34.65

Disp: / Len: 276.13

Comfort Ratio: 24.08

Capsize Screening Formula: 2.02

S#: 1.83

Hull Speed: 6.75 kn

Pounds/Inch Immersion: 989.90 pounds/inch

Rig and Sail Particulars

I: 40.40 ft / 12.31 m

J: 13.40 ft / 4.08 m

P: 34.80 ft / 10.61 m

E: 10.80 ft / 3.29 m

S.A. Fore: 270.68 ft² / 25.15 m²

S.A. Main: 187.92 ft² / 17.46 m²

S.A. Total (100% Fore + Main Triangles): 458.60 ft² / 42.61 m²

S.A./Displ. (calc.): 15.76

Est. Forestay Length: 42.56 ft / 12.97 m

Mast Height from DWL: 44.25 ft / 13.49 m

CONSTRUCTION

The hull of the 303, again differing from many later models, is uncored. Weight was not a concern, and, if keeping a scorecard, we’d give the 303 a point or two for its solid fiberglass hull. Lead ballast is internal, so there are no keel bolts to worry about.

The propeller shaft is molded into the hull. And, as previously mentioned, the rudder is hung on a skeg. While this rudder won’t be as efficient as a balanced spade rudder, it has its advantages, especially for cruising. One thing that might have been done differently would have been locating the lower rudder bearing maybe 6 in. or more above the bottom of the skeg, so if the skeg grounds or hits an object, there is less likelihood of disabling the rudder. An emergency tiller was provided.

End-grain balsa was used in the deck. We’re not exactly sure how the hull/deck joint was fastened, but Pearson had given up through-bolting on many 1970s models, so we assume the 303’s hull and deck were fastened with self-tapping screws. This method saves time, and while perfectly satisfactory for the its coastal purpose, it detracts somewhat from overall quality.

Pearson generally did a good job with details, such as backing plates for hardware, installing bronze seacocks, and choosing quality materials for pulpits, stanchions and the like.

The cabin sole is a one-piece fiberglass molding bonded to the hull. A teak and holly overlay hides it. We like the fact that the berths are not part of this molding, rather built up of plywood, which as we have said many times, is a better acoustic and thermal insulator, and is easier to modify. The teak bulkheads are bonded to the hull, but not, we assume, to the deck, as the one-piece fiberglass overhead must be bonded to the deck before the deck is lowered onto the hull and bulkheads. Some early brochure photos show what appear to be stainless angle braces securing the bulkheads to the deck, intended to prevent working. The head is a fiberglass molding, which is appropriate considering that water from the sink, toilet and shower is a danger to plywood.

We received several complaints about leaks, citing the bedding compound used in portlights and deck hardware—time consuming, but not difficult to fix.

The interior has an attractive amount of oiled teak to highlight the high-pressure laminates used on cabinet facings. Stowage is pretty good for a 30-footer, with three drawers in the galley, a bureau in the forecabin, and stowage behind the settee seatbacks. The hanging locker is short and small, however. The quarter berth was advertised as a double, but as one owner put it, “No way!”

The high freeboard and generous beam make for a lot of space in the cabins. Headroom is 6 ft. 3 in. Freshwater capacity is 38 gallons.

All things considered, construction of the Pearson 303 is above average. That has always been Pearson’s reputation, and we see nothing in the 303 to alter that perception.

PERFORMANCE

The 303 has a keel-stepped mast, which is a nice feature and something that Bill Shaw must have felt strongly about. The mainsail has near end-boom sheeting to a traveler mounting across the cockpit bridgedeck. It won’t be easy to reach from behind the pedestal, but the jib sheets are, as the winches are mounted just forward of the wheel.

While most owners praise the 303’s balance, stability and seakindliness, most are honest about its speed. “Definitely not a racer,” said the owner of a 1984 model. Upwind performance is especially marked down, and this is no doubt due at least in part to the boat’s high freeboard, wide beam and shoal keel. But few owners feel it is a significant problem. Offwind performance is rated more highly.

Typical PHRF ratings from fleets around the country range from 171 to 192, with most in the mid-180s. This is a bit slower than the popular 1970s vintage Pearson 30 at 180, a Cal 30-2 at 174, and a C&C 30 at 168.

Auxiliary propulsion is furnished by a Yanmar 2GMF 13-hp. diesel. Tankage is 22 gallons in an aluminum tank under the cockpit. This would seem on the small side, and a number of owners said so. Others rate boat speed and maneuverability under power as acceptable. One owner said he switched from the standard two-blade prop to a 15 x 11 three-blade prop, making 6.5 knots at 2,000 rpm. Another owner who was critical of the engine size, said he makes 5.5 knots at 2,500 rpm.

CONCLUSION

Market Scan Contact

1983 Pearson 303 Rose Ann Points

$34,900 USD (904) 501-1532

St. Augustine, Florida St. Augustine Sailing

1982 Pearson 303 The Cruising Yacht Brokerage, LLC

$12,900 USD 401-298-2079

Barrington, Rhode Island Yacht World

1985 Pearson 303 Snug Harbor Boats

$22,500 USD 770-741-2677

Buford, Georgia Yacht World

While it’s easy to overlook the Pearson 303 as another member of a fleet that looks depressingly similar and lacking in pizzazz, the 303 is a wholesome family cruiser with a workable, traditional interior, acceptable performance and above average construction. Hey, what’s not to like?

The BUC Research Used Boat Price Guide lists average retail low and high of the 1983 models at $35,300 to $39,100. 1986 models come in at $42,900 to $47,600. A check of asking prices in the classifieds of Soundings corroborates these numbers, but given the state of the used boat market, we’d want to pay no more than the low $30s for a Pearson 303 of any vintage.

OWNERS’ COMMENTS

“Good looking, voluminous hull which sails very well as long as not pressed hard upwind.” —1983 model in Highland Park, Illinois

“Backs up straight and turns on a dime.” —1983 model in Redondo Beach, California

“Feels very capable and relatively dry. Takes a lot of effort to put the rail down. Excellent room for a 30-footer. Damn wheel gets in the way when helmsman wants to trim sheets, especially the main. The 303 is easily handled by two.” —1983 model in Chicago, Illinois

“Steers and tracks very well. Has nice comfortable motion. Would like to have a larger engine for really rough going.” —1985 model in Buffalo, New York

“Yanmar 13-hp. is underpowered for 10,400-lb. boat. Poor chart table. Difficult to open and close through hulls, which are hard to reach. Otherwise, an excellent boat. Would choose again. Very well made. Beautiful design and layout.” —1983 model in Greenville, North Carolina

“This boat will not make you the club racing champ, but it is superb for a daysailer and for cruising. It is seakindly, comfortable and well made.” —1984 model in Potomac, Maryland

“Hull and keel design make for poor upwind performance. Built like a tank. We added a three-blade prop. V-berth large and comfortable. Head is super. Cockpit is small.” —1984 model in Wayland, Massachusetts

“Terrible access to raw water valve and transmission oil.” —1983 model in Greenville, North Carolina

“I’m 6′ 4″ tall and can stand upright in the entire main cabin and in the shower/head. Berths are also long enough. When heeled, water on high side deck drains onto the cockpit seats. Changing oil filter and accessibility to dipstick and filler cap is difficult.” —1984 model in Binghamton, New York

“This boat was designed more for cruising than racing. Light wind and downwind performance is ordinary. Below decks, she is probably the biggest, most comfortable 30-footer afloat. Points very well. A perfect boat for a cruising couple. You will have to spend much more and get a much longer boat to get more room.” —1984 model in Framingham, Massachusetts

“Ventilation best of any boat we’ve been on. Suggest you get a 3-blade prop. Install a propane stove and anchor chock as the anchor is cumbersome to get around a roller furling drum. Boat needs better placement of fairleads for larger genoas.” —1984 model in Vienna, Virginia

This article was first published on 19 March 2016 and has been updated.

Why do you say that the one thing she is not is an “offshore passage making boat”. I am a passage making sailor and am interested in making passages with this boat so I need to know what reasons you have that says I should not.

What Mo said. Hull to deck joint needs bolts not self tapping screws. Tabbing in the bulkheads could be better, Volume of cockpit is too large, Port lights are plastic. Read John Vigor’s “The Seaworthy Offshore Sailboat” for a detailed analysis/opinion of good characteristics for an “offshore passage making boat” . The 303 like the 323 could be made into a sturdy offshore boat but as it is off the production line it’s a coastal boat according to Pearson but a solid, well built coastal boat at that.

The self-tapping screws as opposed to bolts is the number one reason. I’ve a 1983 Pearson 303 and treat her as a coastal cruiser . At my present age 65 and preferring to single hand I find the 303 suitable form my “wants in a sailboat. She’s sturdy, she’s roomy for a boat in the 30 foot range. I’ve added davits and a custom chart table (which I prefer to the one Pearson added in either 84 or 85.)

I’ve downsized as the family has grown and my needs for long-range crusing has diminished. Went from a 52’ Irwin’s cutter/ketch rig istraring ion the nis 1980s to a 37’ Fisher Motorsailer in the first decade of the 2000s. Also kept an Ericsson 32’ after selling the Fisher (which, to this day, I wish I had kept). Did not like the Ericsson for my needs and “wants” l. Then went through a quick succession of a modified Grampian that The previous owner had lengthened and put some heavy standing rigging replacement. She ended up being around 34’. Let her go quickly and cheaply. Then an Irwin Citation 34’ the year I don’t recall because I got rid of her quickly.

I took a few years looking for a good deal on a Pearson 303. I purchased the 1983 hull#065 and began the process of bringing her up to my needs a little over two years ago. With the additions and upgrades. (Yanmar) ,

Motor mounts, davits, nav table, I’m a happy Pearson owner again. “Cripple Creek” suits me across the board for now.