When cousins Clint and Everett Pearson took the first Pearson Triton to the 1959 New York Boat Show, they had no idea that ultimately they would build more than 700 hulls, the boat would establish Pearson Yachts as a premier builder of fiberglass boats, and that more myths would surround the Triton than practically any other boat of its time.

Returning to their Bristol, Rhode Island yard with 16 orders in hand, the success of the young company was assured.

We owned a Triton for a number of years, cruising it from the Great Lakes to the East Coast. Our affection has not blinded us, however, as ownership also exposed the boat’s several problem areas. In any case, this is a landmark boat that many good sailors cut their teeth on.

History

Myth: The Triton was the first production fiberglass sailboat auxiliary. Not true. The Rhodes-designed Bounty, built by Fred Coleman, owns that distinction.

The story of Pearson Yachts is well documented, so we’ll repeat here just the essentials. The company was founded in 1956 and built rowboats, dinghies and runabouts until the Triton arrived in 1959. A few were built in Sausilito, California, but the venture wasn’t to last long. During the next few years, Carl Alberg and Philip Rhodes accounted for more than half a dozen other designs, including the Vanguard, Alberg 35, Bounty II and Rhodes 41. The last Triton was launched in 1967.

In 1964 the company was bought by Grumman Allied Industries. Clint Pearson later left to start Bristol Yachts and later yet Everett departed to form a partnership known as Tillotson-Pearson. Bill Shaw emerged as the principal designer and later served as president. In 1990 Pearson went bankrupt and its assets were auctioned off. Aqua Buoy bought the molds but despite promises to resume production on a limited basis, no new boats have been built since. Blame the recession in part.

It’s a sad ending to what was once a very fine boatbuilding company. To this day, many of the early Pearsons are still sailing, and, to our mind, represent some of the best buys on the market.

Design

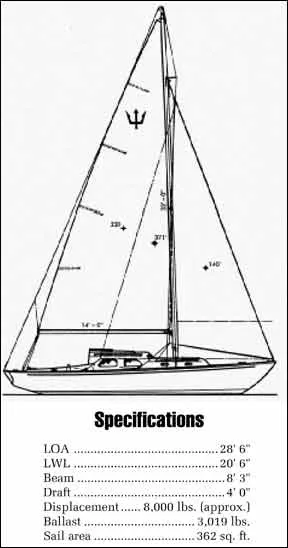

The Triton is vintage Alberg—skinny, long overhangs, low freeboard, large mainsail and small foretriangle. Typical of boats designed to the CCA (Cruising Club of America) rule. Alberg was born in Sweden where people love skinny keelboats with long overhangs, such as the Folkboat. It is easy to trace the Triton’s lineage to such designs. Credit is also due to Tom Potter, of Jamestown, Rhode Island, who brought the project idea to the Pearsons, and had a hand in its development.

Many folks refer to the underbody as a full keel, but as a glance at the profile drawing shows, the forefoot is well pared away, and the rudder is located below the helmsman. The keel is long enough to provide excellent directional stability and minimize leeway. Still, there’s a lot of wetted surface by today’s standard.

There were so many changes made to the Triton over its nine-year production run, one could fill a book trying to mention every one. Displacement, for example, is listed at 6,930 pounds until the last year or so, when it was changed to 8,400 pounds. Like most boats, if you actually weighed them they’d probably come in all over the place. The ballast-to-displacement ratio of the lighter models is 44 percent, which coupled with the Triton’s fairly firm bilges, gives her plenty of stability.

An aesthetic problem of Alberg’s smaller designs is caused by the low freeboard; the cabin trunk, to provide headroom, is tall and rather ungainly looking. There’s six-foot-plus headroom in the main cabin, but the step in the coachroof reduces headroom forward to well below six feet.

The cockpit is long enough to lie down in, yet even when pooped (it happened to us), won’t hold enough water to threaten the boat. The bridge deck, which adds a measure of safety for offshore work, certainly helps. Some of the earliest boats had side-opening seat lockers, which are dangerous unless modified to seal tightly.

The original rig was a three-quarter fractional rig, however, a somewhat shorter masthead rig was later available, though it didn’t perform quite as well. A number of boats were built with yawl rigs (the main mast was shortened two feet and the boom one foot). The jumper struts on the fractional spars make the Triton easy to identify at a distance. The early Tritons were rigged with single lower shrouds, which proved inadequate. Richard Henderson, in his book, Choice Yacht Designs, reports that after about hull #120, double lower shrouds were standard and rigging kits supplied to owners of existing boats. We have several reports of rigging tangs failing; as with any old boat, we’d check the rigging carefully before subjecting the boat to much wind.

Despite the Triton’s tall cabin, she is an attractive boat, especially if viewed from the classic photographer’s position at the quarters or off the bows.

Construction

Myth: The hull of the Triton is an inch thick. Not true. Despite the fish stories of owners, the hull thickness varies from about 3/8-inch at the rail to perhaps 3/4-inch in the keel area. When you drill holes for transducers, you’ll be cutting through about 5/8-inch. Nevertheless, this is a good solid hull, though we have noticed, when examining hull plugs that some fibers were not completely wetted out.

Recently we heard from a former Triton owner in the Caribbean who lost his boat to Hurricane Hugo. Larger boats dragged down on it and carried it onto the beach at the St. Croix Yacht Club. “It finished up outside one boat,” he wrote, “inside two others and with another two on top. That magnificently built hull was completely intact, albeit with a few gouges. The deck had always been weak and it was penetrated by the intruders; in places it had parted from the hull, another soft area. We pumped it out, waterblasted it, and sold it to someone who patched it up, sorted out and resurrected the mast, and now lives on board.”

The Triton was built of conventional mat, cloth and woven roving, and polyester resin. Balsa core was used in the decks. Ballast, in boats after about hull #385, is cast lead lowered into the keel cavity and glassed over (which widened the keel two inches and deepened the draft about one inch). Voids in this area are commonplace. Water entering the cavity from a grounding theoretically should not enter the cabin, but repair is messy if straightforward. The earlier boats had external ballast. Which is better is the subject of constant debate. Internal ballast obviates the need for keel bolts, which are a source of concern and maintenance. On the other hand, grounding labor intensive.

Besides deck delamination, which is common to many old boats, a weakness of the Triton is insufficient load-carrying ability of the beams that support the deck-stepped mast. Because the walkway is on centerline, the main bulkhead and the one separating the head from the forward cabin cannot take all of the loads. A square beam was fastened to the forward bulkhead and run underneath the deck; it is supported at either end by beams that run down the bulkhead to the hull. Nevertheless, numerous owners report caving of the deck underneath the mast. Repair means unstepping the spar, removing the beams and replacing them with new, stouter materials. Not an easy job, but not too tricky either.

Any boat as old as the Triton (more than a couple of decades) cannot hope to retain its original gel coat. Most Tritons have been painted, a few may have been sprayed with new gel coat.

In looking at Tritons for sale, the quality of the paint job may be a decisive factor. A professional or well-done home job is probably worth paying a little extra for. Be wary of the amateur paint job in which the owner has prepped with a sander run amok: telltale little half-moons visible when the light is right.

Our late model Triton was delivered standard with a lightning ground system, bronze Wilcox-Crittenden seacocks and generally good quality hardware. The South Coast winches are out-of-date now, but still serviceable. A nice set of self-tailers would be a great upgrade, but they’re expensive. The spreader sockets are aluminum sand castings and can break without warning. Also check for electrolysis of the bronze rudder shoe.

The rudder was built of mahogany with bronze drift pins. Over the years the expansion and contraction of the wood (during haul-out) causes cracks to develop. Many owners have had to build new rudders, sometimes opting for fiberglass. A few have redesigned the rudders as well, usually by squaring and giving more depth to the trailing edge to help fight weather helm. This is the shape Alberg specified in a later redrawing of the Triton for Henderson’s book.

Interior

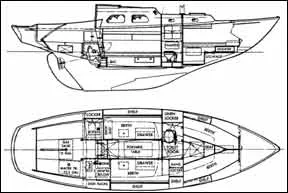

The Triton’s interior plan is simple. The 6′ 3″ settees in the main cabin double as sleeping berths. They are wider than normal, so it is often necessary to place a pillow behind your back for comfort. The head is private but small.

Furniture components are plywood covered with plastic veneer intended to look like teak. This makes for a dark cabin. You can paint the veneer, but it needs a good scuffing to hold paint, and will still chip. People have tried just about everything to get rid of it, including gluing mildew-resistant designer fabrics to the surfaces.

The sole is teak, supported by wooden, athwartship beams (“floors”). A wet bilge can cause these to rot, so inspect beneath the sole carefully.

The icebox also is built up out of plywood, with just an inch or two of styrofoam in the middle. Equally bad is its side-loading door. This method of construction and design won’t keep ice for long, and again, many owners have rebuilt theirs. Unfortunately, the original location doesn’t allow for much expansion, so you may need to relocate the box to the head of a settee. Any owner or prospective owner of a Triton should read Spurr’s Boatbook: Upgradingthe Cruising Sailboat, which details many of the modifications necessary.

Regarding the ice box, you’ll also note that there’s access to its upper shelf from the cockpit, which was a clever way of grabbing beers, but does nothing to help retain ice.

The early Tritons did not have a headliner anywhere inside. Later, a gel-coated fiberglass liner was added to the main cabin, which improves its looks enormously. The forward cabin, in all but the last Tritons, was unfortunately left bare. You may see the original, dreaded, speckled spray paint jobs there, but most owners will have painted it over.

The best feature of the Triton’s interior is the pair of forward-facing, opening portholes in the main cabin. These are situated at the step in the coachroof, and provide excellent ventilation down below as well as allowing you to see forward, a feature seldom found on other boats.

Engine

The 30-hp Atomic 4 was the standard powerplant, which provides more than enough power and easily drives the boat at hull speed—a little more than six knots. Access is not any better than any other boat of this size, but by removing the companionway ladder the front end can be worked on fairly easily. You’ll need your kid to tighten the stuffing box.

So many of these engines were built, and so many are still in service, we won’t bother to detail all the problems, solutions and repowering considerations attendant to the Atomic 4. Suffice to say that if you like tinkering with engines, the Atomic 4 is simple and can be successfully goaded to perform adequately. Some Tritons have been repowered, most often, we suspect, with Universal’s four-cylinder diesel, which was billed as a drop-in replacement. To the best of our knowledge, some modification of the engine beds still is required. A major problem, of course, is corrosion due to sea water cooling.

Performance in reverse, as with nearly all boats of this type with long keels and propellers in apertures, is unpredictable. But that has nothing to do with the engine.

Performance

The Triton is surprisingly quick for her short waterline, which when the boat is heeled, lengthens nicely.

The boat heels rapidly to about 15 degrees, then stiffens satisfyingly. It’s tough to push the rail under, though it can and has been done often. Water still won’t enter the cockpit.

The nice thing about this type of boat is that you can carry on over-canvased without stalling the rudder. Just luff the mainsail a bit and even the gusts won’t send you reeling out of control, as often happens with spade rudders. And it tracks well. Consequently, the Triton is a very forgiving boat, especially for the beginner.

Because of its large mainsail and small foretriangle, the boat has weather helm when carrying working sails. Better to carry a #2 genoa and reef the main. That way you’ll balance the sail plan better and find the helm easier to manage.

The PHRF rating of the Triton averages about 246. There aren’t many boats slower in the U.S.S.A. listings. For comparison, how about a Tanzer 22 or Venture 25? The Tartan 27, a S&S design of similar vintage, rates 228. These figures can be misleading, however. We recall sailing away from an entire fleet of Pearson boats during one of the builder’s rendezvous on Narragansett Bay. Whipping a Sabre 28 (PHRF—192) another day. Perhaps we were borne by some favorable and undetected current, which no doubt gives rise to those familar comments of “shows her heels to a lot of larger boats.”

In any case, the rating does allow for competitive sailing. We placed first and second in our only two PHRF races. And for cruising, which is her forte, speed is just fine for such a short waterline.

Conclusion

Prices of Pearson Tritons peaked in the early 1980s at about $18,000. Since then, their value has dropped along with practically every other boat. And, of course, they’re getting older, requiring more time and money to keep in shape or upgrade. Today you can buy a Triton for less than $10,000, which makes her a real bargain. (You’ll pay in the low teens for a good one.) We feel fairly confident in saying that it is the smallest, most affordable offshore boat you can buy. At least one has circumnavigated, Jim Baldwin in Atom. And we know of many others that have made safe trans-oceanic passages. You should consider fitting storm shutters to the main cabin windows, as they are on the border of being too large.

It’s too bad that Pearson is out of business, as they always had a good customer service department. Over the years we’ve obtained old parts from them, or referrals to the original suppliers, even foundries for bronze and aluminum castings.

If you’re on a budget and willing to do your own upgrading, the Triton at least gives you a solid structure as a starting point. Given the strength of the hull, devotion of owners, and active owner’s association (National Triton Association, 300 Spencer Ave., East Greenwich, RI 02818; (401) 884-1094) with active racing and rendezvous in most parts of the country, we fully expect to see the Triton well into the next century.

I’m A ! Proud Owner of a 1966 Pearson Triton 29.5 Built on the East Coast and first purchased there I am the third owner!

It is Docked in Oceanside Calif.

Hi Michael,

I’d like to ask you some questions about your gas tank. I also have a 1966 Pearson Triton 28.5 and live in San Diego.