Pearson Yachts, of Portsmouth, Rhode Island, was founded in 1956 by cousins Clinton and Everett Pearson, and fellow Brown University graduate Fred Heald. For the first few years it produced dinghies and runabouts in fiberglass, a boatbuilding material pioneered in the early days of post-war America by Ray Greene, Taylor Winner and a handful of other erstwhile inventors. Then in 1959 Pearson exhibited its prototype Carl Alberg-Designed Triton at the New York Boat Show, wrote enough orders to pay its hotel bill, and sold public stock to raise the necessary capital to expand facilities. The Triton, while not the first auxiliary sailboat built of fiberglass, was the first boat to enjoy a long production run (over 700), and keep its builders in the black.

The Vanguard, designed by Philip Rhodes, followed in 1962 and remained in production until 1967, totalling 404 hulls. It was preceded by the Invicta, Alberg 35, Bounty II, Ariel, Rhodes 41, and of course the Triton. This line of fiberglass cruisers and sometime racers gave Pearson a strong position in the market. The pedigree of the designers was odorless, and construction quality was good for that particular moment in the timetable of plastic boatbuilding technology.

Sailing Performance

The early Pearsons were club raced with moderate success under the now-defunct CCA Rule, and in some offshore events. Indeed, the 37′ Invicta yawl Burgoo won the 1964 Bermuda Race. It was the first time a fiberglass boat had won the event and prompted a lot of advertising ballyhoo from the company. While the Vanguard never acquired as memorable a victory as the Invicta, it performed decently.

One does not, however, buy a vintage Pearson for scintillating performance. A PHRF rating of 216 indicates the Vanguard will spend a lot of time watching the transom of even a Pearson 32, a 1979 design with a divided keel and rudder underbody whose rating is 174. The reasons include greater displacement and shorter waterline. The theoretical hull speed of the Vanguard’s 22′ 4″ waterline is just 6.3 knots. As the boat heels, however, the waterline’s sailing length quickly increases, as will speed. Therefore, the Vanguard was intended to sail at about 15° of heel for maximum efficiency. Once its “shoulder” is immersed, the boat is fairly stiff.

Maneuverability is good. Comments from our reader surveys say, “Turns on a dime.” Despite bearing the “full keel” appellation, the Vanguard’s generous overhangs, cutaway forefoot and raked rudderpost mean there’s not as much lateral surface area as one might suppose. Backing down is dreadful, but that’s to be expected with a keel-hung rudder and propeller in the aperture. One learns to aim in the direction of the prop; to attempt otherwise is to thumb your nose at physics and invite the maledictions of watchful owners on nearby boats.

Like many CCA-inspired designs with large mainsails and small foretriangles, the Vanguard likes to carry a large headsail longer than is customary on more contemporary designs. Instead of switching down from, say, a 150% or 165% genoa when the wind approaches 18 knots, the wiser practice is to reef the main. The consequence of any other strategy is a wicked weather helm that makes tiller steering seem like a two-handed wrassle with an alligator.

Owners have dealt with the weather helm problem in various ways. Because raking the mast forward (to move the center of effort forward) is an insufficient measure, some have installed double-duty bow platforms to relocate the headstay farther forward, and as a permanent home for their main anchor. Others have tried roachless mainsails. The easiest solution is simply to adjust your thinking about sail combinations. As one reader wrote, “It took me three years to learn to shorten the main (before reducing headsail size).”

A small number of Vanguards were delivered with yawl rigs, and though none of the readers in our survey were owners of split rigs, they presumably would be easier to balance than the sloop.

Despite these idiosyncracies, the Vanguard is well behaved in deteriorating weather. It is never skittish while tacking or during sail-changing maneuvers, and in fact, by luffing the mainsail it is possible to carry sail longer than is prudent. Switching down, of course, is inevitable. “In 50 knots with a storm jib and trysail,” said one reader, “she can make three knots to windward.”

Engine

The ubiquitous Atomic 4 gasoline engine was the standard auxiliary for the Vanguard. Many are still in operation though it is more and more common to find thrifty replacement diesels, a certain improvement in resale value. If the Atomic 4 hasn’t been replaced yet, one should factor in the cost of repowering in the not-so-distant future.

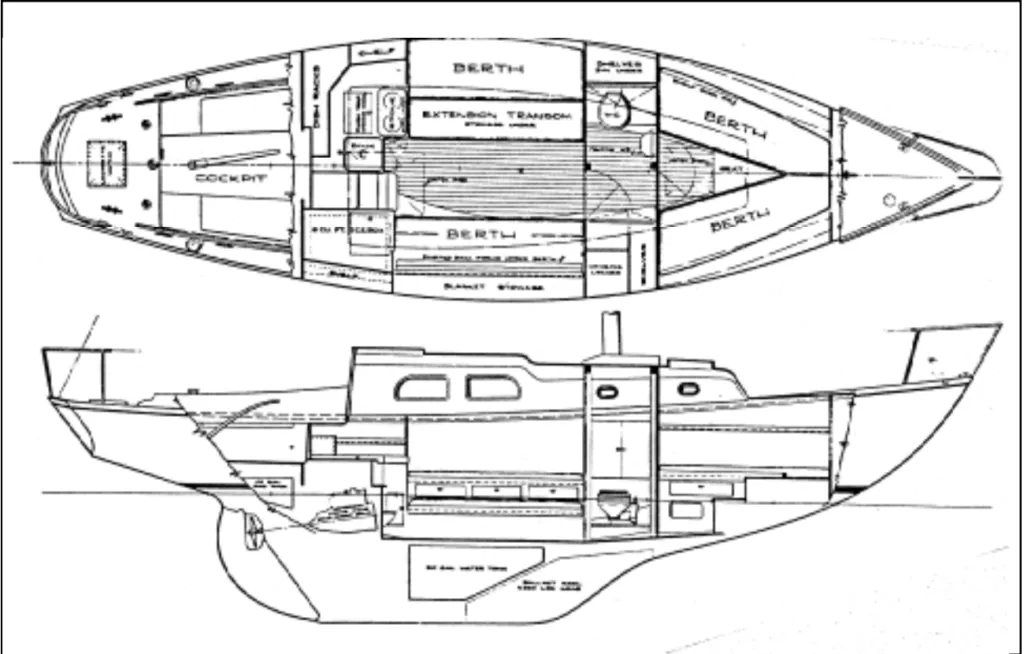

Accessibility varies dramatically between the standard aft galley layout and the dinette arrangement with quarter berths aft. In the first, the engine is located under the sink; access is from the front via a cupboard door and from the side by removing the offset companionway counter steps. Needless to say, this is not a convenient setup for even routine oil changing, let alone major repair work. In the second, the engine is covered by a box directly under the bridgedeck; removable panels, fastened by knurled thumbscrews, expose the engine on all sides except the aft transmission end, which is under the bridge deck. While ease of engine maintenance is certainly an important factor in choosing a boat, in the case of the Vanguard the two general arrangement plans also have significant impact on livability at anchor and at sea, giving prospective buyers pause to contemplate the many implications of the two different layouts. More on this later.

Construction

Owners’ faith in the integrity of older Pearsons borders on the religious. “They don’t make ’em like they used to!” is a frequent call in the hallelujah chorus of these proselytes, usually followed by some refrain of boatyard wisdom such as, “Back then they didn’t know how thick fiberglass had to be.” Or they say, “My hull is…this thick!” as the space between their thumb and finger grows like Pinocchio’s nose. There is probably some truth to these beliefs—that scan’tlings for fiberglass boats were for a time loosely derived from the builder’s knowledge of wooden boats—but a thick skin doesn’t necessarily result in a well made boat, nor does the hull layup tell the whole construction story. Amen.

The Vanguard’s single skin hull was indeed the beneficiary of generous laminations of 1 1/2-ounce mat and 24-ounce woven roving, but probably not as many as some owners would like to believe. One indication of panel stiffness is whether the hull changes shape in its cradle; a door that suddenly won’t open is a telling clue, and with the Vanguard, this is seldom the case. It is also true that most Vanguards weigh about 1,500 pounds more than the designed displacement.

Perhaps the most dramatic difference between old and new Pearsons (and most older boats for that matter) is the use today of many more fiberglass molds: furniture foundations, iceboxes, shower stalls, etc. In some instances this practice may represent an improvement, in others not. The Vanguard’s interior was constructed of plywood taped to the hull. Correct building procedures were generally followed, such as peeling the plastic laminate where bulkheads are taped to the hull for better adhesion. Neatness, however, sometimes was lacking; examples might include wrinkles in the cloth and frayed, untrimmed edges.

The all-wood interior, properly taped to the hull, nevertheless creates a strong internal support structure and is amenable to do-it-yourself modification. Where it becomes unsatisfactory is in some structures such as the icebox, which in the Vanguard was built in situ from plywood and sheets of Styrofoam; the result is too many thermal leaks, not enough insulation, and more weight than necessary. Owners wishing to upgrade the icebox have the dubious choice of adding insulation on the inside (resulting in an unacceptably small box) or ripping out the entire box and building a new one from scratch, which is a devil of a job.

The deck is balsa cored and the hull-to-deck joint is a simple flange that is sealed and through-bolted. The balsa is terminated several inches from the rail so that deck hardware such as lifeline stanchions and cleats are mounted on solid glass. As with most older boats, bedding compound tends to deteriorate over time, and severe gelcoat cracking allows the ingress of water. This is of particular concern where coring is involved. Extreme remedies for punky decks—grinding away one skin of the deck sandwich, removing watersoaked wood and reglassing—is a major and costly project.

The one real problem with the Vanguard’s basic structure is the keel (it’s not a problem as long as you don’t hit anything, but groundings, for the curious cruiser, are as predictable as the tide). The lead ballast castings were set in a bed of resin inside the hollow keel, which is part of the hull mold, then glassed over so that water entering the keel cavity will not enter the cabin. Without fiberglass reinforcement, the resin bed is brittle and provides little added protection from a grounding. Voids between the ballast and keel sides were filled with various types of material over the years, including sheets of balsa, which can soak up water like sponges if the keel is holed.

The Vanguard’s mast step is a welded steel box bolted to the deck. Twenty years seems to be about the maximum useful life of these steps, eventually succumbing to rust and requiring the custom fabrication of a new one. Entrance to the forward cabin is offset to starboard so that a solid teak compression post could be fitted to the head side of the bulkhead.

Fuel (21 gals) and water (45 gals) tanks are Monel, the former mounted under the cockpit footwell and the latter under the main cabin sole on centerline. The fuel tank should be removable, but replacing the water tank would require dismantling the sole, which unfortunately is not an unusual situation in many boats. On the plus side, Monel is an excellent tank material and will probably survive the boat itself. Plumbing is straightforward with bronze, barreltype seacocks on through-hull fittings.

Interior

Most owners have strong opinions about the two arrangement plans—standard and dinette. Neither is without problems. The forward cabin is the same in both plans, as is the head. In the main cabin, the standard arrangement features a settee/berth to starboard with a pipe berth over; to port is an extension settee that pulls out to form a full-width single berth and a pilot berth outboard, totaling four decent sea berths. The aft galley is divided by the offset companionway with icebox to starboard and sink and stove to port. There is no provision for an oven in this plan, which may be a drawback for live-aboards and some cruisers. The fold-down bulkhead-mounted table makes for more open space but is something of a contraption.

The dinette plan has a more useful table, which is handy for chartwork and lowers to form a double berth. But because of the Vanguard’s comparatively narrow beam, the dinette is small. The galley is a sideboard affair with adequate plate and food stowage.

Its chief advantage is a three-burner stove/oven, and its greatest liability is a sink that won’t drain with the rail down on port tack. In fact, in such conditions the sink overflows into the stowage bins behind and ultimately into the bilge. This requires closing the sink drain seacock in blustery weather. Two quarter-berths are secure at sea though adults might find them a bit claustrophobic on a regular basis. But at least they won’t have to be stripped of bedding each morning, as do settee berths in the main cabin.

The stepped coachroof provides unusual headroom in the main cabin (about 6′ 5″), and marginal headroom in the head and forward cabin (6′ 0″ plus). Berth lengths are all just over 6’. The head is small, though there is adequate stowage space, and an aluminum fold-down sink at least makes shaving a semi-civilized possibility.

The Vanguard’s interior is virtually all plywood, with bulkheads and furniture foundations taped to the hull. The imitation teak-grain plastic laminate is hardly the fashion today, and contributes to a drab, dark feeling inside. The cabins could be given a real breath of life by painting over the laminate (good sanding required for adhesion, though results may still be marginal) or applying a new veneer on top.

A molded fiberglass inner liner was used for the overhead, and the hull sides are covered with vinyl, the latter being a popular target of home renovation projects. The installation of a wood ceiling or cementing some durable fabric or other foam-backed material is a relatively easy and quick way to spruce up the interior. Fiddles, moldings, handholds and other trim are teak. The cabin sole is teak over plywood, and the floors are wood fiberglassed to the hull.

Conclusions

A reasonable shoal draft of 4′ 6″ makes the Vanguard suitable for cruising the Bahamas and Florida Keys, yet also gives it enough stability for offshore sailing. Perhaps the boat’s major drawback for living aboard or extended cruising is its size; a short waterline and narrow beam condemn owners to stowing on deck surplus drinking water and fuels, sail bags, ground tackle and the like.

Prospective buyers cannot ignore age either; at more than 25 years old, wiring, bedding compound, wood, plastic and metal parts experience a steady rate of failure when a boat gets this old. If the boat hasn’t been the beneficiary of a major upgrading effort, it soon will.

The Pearson Vanguard is a traditionally styled boat, and therein lies her appeal. Rhodes could draw a mean sheerline and this boat is no exception. Like most of the early Pearsons, the Vanguard offers a lot of boat for the money. Its value peaked in the early 1980s between the high $20s and low $30s, more than twice it’s original cost. In recent years, age and the glut of used boats on the market has brought prices down well below $30,000, often into the teens. Much depends on the amount of upgrading performed by past owners, the most important being engine, topside reconditioning, interior customization, condition of teak and non-skid, and sail inventory.