For several generations, performance sailboats fell into several clearly defined groups: Boats like 505s, Ravens and Fireballs were an easy way to enter the racing world, earn your spurs, and prepare for a first appearance with the big guys. These racers were prepared to get wet, subsist on dampened sandwiches and sleep in the back of the station wagon.

The step up to larger boats was generally accompanied by a major change in the performance characteristics of the competition. While some skippers opted for boats with decent speed coupled with some cruising amenities, like galleys and enclosed heads, serious competitors looked more to purpose built boats, where cost is measured as a function of boat speed. Owners of Ericson 27s and Catalina 27s, who had filled trophy cases with the spoils of their victories, learned that Dacron sails had gone the way of the Model A, as had old deck layouts, teak and holly soles, and water tanks filled with anything heavier than air. Some one-design fleets voted to sail the old-fashioned way, but most racers found themselves writing checks to purchase speed. Coupled with a slowdown in the economy and changes in tax laws that penalized big-spenders, the market for new racing boats began a decline in the 80s that resulted in the closing of many yards. There will always be a small market for the occasional Reichel/Pugh 70, the ILC 40 and Mumm 36, but those boats are being sailed at the highest levels of the sport. The used boat market has become saturated with aging warriors no longer called to battle.

Sportboats—The New Breed

At the other end of the spectrum, a handful of enterprising sailors made an important realization: If the over 30-foot market was soft, and the number of people attracted to racing was stable or increasing, the place to fill the void was with smaller, less expensive boats. Several fixed-keel daysailers fit the bill, such as the J/24, Soling and Etchells, tremendously competitive one-design fleets. But there still seemed room for a high-performance trailerable racer with just enough cruising comfort to be marketed as a dual-purpose boat.

By the mid-80s, Bruce Farr was cutting a wide swath through the industry by continuing a design evolution originating with the Farr 36, a beamy, fractionally-rigged boat that was quick to weather, and very fast on a reach. Farr designs were winning at every level, from 36-footers at the SORC to Whitbread maxis, and shared several common characteristics: deep keels, wide beams carried aft, and flat aftersections. These boats were best sailed like dinghies.

With the window of opportunity wide open, Bill Tripp designed the 26, Reichel/Pugh designed the Melges 24, Rod Johnstone designed a new series of Jboats and voila! Big boat racers began gravitating to smaller boats without giving up the thrill of speed, yet avoiding many of the hassles involved in big league campaigns.

The Boat

The Tripp 26 is the product of a collaboration between Smart Boats, a Newton, Massachusetts marketing company headed by Tom Donnelly, designer Tripp, and Barry Carroll of Carroll Marine. Since the first commissioning in 1992, more than 35 have been produced. However, they are now built by Mark Lindsay Boat Builders in Boston because Carroll Marine was unwilling to deal with sporadic orders for small quantities. Plus, he’d picked up the hot Mumm 36.

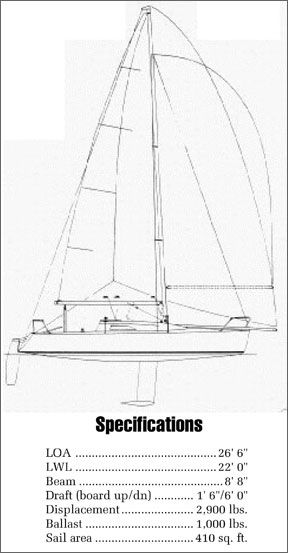

This 26-footer is totally unlike familiar racer/cruisers from Pearson, Catalina or Hunter. For openers, it looks like a hot rod. The fine entry of its plumb bow and reverse transom give it a grand prix look, as does its 8′ 8″ beam. The boat displaces only 2,900 pounds on a 22′ 0″ waterline. It has a 7/8 rig supported by a pair of swept-back spreaders. Standing rigging is 3/16″ wire on the uppers, forestay and lowers, 5/32″ on the intermediates and running backstays. Ease of movement along wide decks is assisted by inboard shrouds.

The main, jib, two spinnaker halyards and the topping lift are housed inside the Hall Spars mast, leading aft through turning blocks to Spinlock rope clutches and a pair of Barient 17 winches on each side of the cabin top. The outhaul, a soft vang with Harken blocks and a Cunningham provide additional mainsail controls.

Because a key component of performance is the need to keep the boat level, two Barient 21 winches are located well forward in the cockpit, so trimming headsails is easily accomplished from the weather rail. Harken ratchet blocks attached to the base of the stern pulpit are used to trim spinnaker sheets, which are then led forward across the cockpit, also allowing trimmers to work from the weather rail.

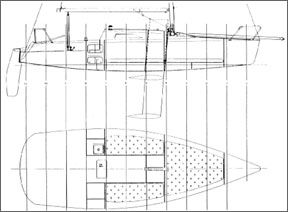

With only two people aboard, the cockpit feels like a dance floor. It’s almost 8′ long, 5′ feet wide and 1′ deep so there’s plenty of room to stretch your legs while seated on the 1′ wide deck. The feeling of spaciousness is enhanced by an open transom. The fiberglass tiller is fairly unobtrusive because steering is done from the rail with a tiller extension. The main sheet is easy to manage from either side of the boat because it’s attached at the boom end and runs through Harken blocks to a swiveled cleat located amidships on the cockpit sole just forward of the traveler track, which is recessed into the cockpit sole. Double-ended lines lead from a Harken traveler car to cam cleats, so the helmsman has both main controls at his fingertips when sailing shorthanded.

An accommodation to crew comfort is a smooth deck amidships, so hiking out on the weather rail shouldn’t result in bruises on the backs of legs. A toerail glassed into the deck is located inside the lifeline stanchions and runs forward from the shrouds to the bow pulpit, providing a measure of foredeck security.

The flip side of the spacious cockpit is a paucity of space belowdecks (there’s not much room for the washer and dryer).

However, the aft section is wide open for storing provisions and other necessities when not racing.

A flush-mounted Bosworth manual bilge pump built into the port side of the cockpit is barely noticeable until one encounters a 20′ section of 1-1/2″ hose stored in the port quarter, a tidy arrangement as the boat doesn’t have a conventional bilge.

Construction

The hull is constructed of hand-laid biaxial E-glass on balsa core using vinylester resin. Vinylester has excellent bond strength and in our tests has proven superior in resisting the transmission of moisture and water vapor, thereby minimizing the chance of blisters. Because most boats will be dry-sailed, blistering is not that much of a concern. The Tripp 26 carries a five-year warranty against blisters and a one-year warranty on everything else.

The hull-deck joint is shoe box style, with self-tapping stainless steel fasteners bedded into a wood sheer strip with 3M 5200 sealant. The seam is covered with a stainless steel rubrail.

Some early Carroll-built boats experienced rudder failures. We asked Joe DaPonte of J-Cam, which fabricates the basic structures for Mark Lindsay, about this and were told that instead of molding the rudder in halves, bonding the two and pumping foam into the voids, J-Cam cuts the foam to fit, bonds the foam to the insides of the molds using Multi-

Bond putty, then glasses the two halves together. They have added a small overlap to the top of the rudder that allows three layers of glass around the leading edge and over the top. DaPonte said this adds 2-3 lbs. to the weight of the rudder, but they have had no problems in the five boats they’ve built.

One key to the boat’s performance is a 1,000-pound retractable bulb keel drawing 6′. As a consequence, the keel trunk, which is located amidships near a bulkhead, takes up a lot of visual space below. Otherwise, it is not much more intrusive than a conventional centerboard trunk. Hoisting the keel takes a bit of strength, however, so an alternative to a weight lifting program is an optional electric winch. But we’d figure out some way to use a simple block and tackle before adding the weight and expense of an electrical modification. A large stainless pin holds the keel in position.

At present there is no foam flotation though the builders and developers have discussed adding it. With a conventional companionway drop board and a cockpit that drains through the open transom, the boat can be buttoned up, as it should be in rough weather.

Interior

Because weight is so critical in this type of boat, accommodations are functional but Spartan. Galley and settee/berths are part of a fiberglass structural pan running from under the companionway forward to a bulkhead that stiffens hull sections while supporting keel loads at the keel trunk and carrying mast and rig loads to the hull. To port, a small sink served by a hand pump is housed in a small cutout over an area large enough to store a 5-gallon water jug. Cold storage is provided by an Igloo ice chest that doubles as a companionway step, secured to the cabin sole by tie-downs.

A caution: If the ties aren’t secured, the chest loses all stability and becomes an ankle-twister. A one burner Origo alcohol stove to starboard is located opposite the sink. Single settee/berths located amidships on each side of the boat are 7′ long, under which are small storage cubbies.

Small storage compartments are located on each side of the keel trunk.

Except for running lights and interior lighting, there’s little need for electricity. A six-breaker circuit panel is provided. Immediately forward of the keel trunk is a spot designed to house a portable toilet and double berth, partially separated from the saloon by a bulkhead to which the chainplates have been attached. The area could easily be privatized with a little imagination-a piece of fabric and hookand-loop fasteners. The forepeak is advertised as sleeping two, but the designers must have imagined that short boats have short crews. In reality, to sleep four on this boat probably means having one crewmember sleep on the cabin sole or in the cockpit.

All things considered, the area belowdecks is nicely finished. Surfaces and joints are finished smoothly and in white, so most maintenance tasks will be performed with a bucket of soapy water and sponge.

Performance

This is a boat that begs to be sailed away from the dock, as we did, ghosting along at 4 knots in light winds on a chilly winter day.

With a 150-percent genoa hoisted on the headfoil, it responded quickly to 6-8 knot breezes, heeling about 15 degrees, reaching hull speed quickly with a touch of weather helm. In these winds, the Tripp 26 was stable with just two crew. It points like an English setter.

Sailing in smooth water, we eased the traveler in 10-12-knot puffs and the boat responded by lowering its shoulder and powering on.

The shallow hull and large sail plan contribute a lot to the 26’s performance, which is further enhanced by a factory-faired rudder and keel combination that adds stability and balance. The boat really kicked up its heels when we eased sheets and footed off to 60 degrees of apparent wind.

“We’ve had her surfing at 15 knots in 25 knots of breeze, and she’s real stable,” said Bob Ross of HCH Marine, the Seattle distributor.

Unlike newer designs that feature retractable bowsprits, the Tripp 26 sails with a conventional spinnaker arrangement, and a penalty pole that increases speed more than the offsetting increase in rating. In most areas, the Tripp 26 will rate 105-110 under PHRF, which will put it in fleets of Olson 30s, J/29s and other pocket rockets. Like most boats of this ilk, it’s happiest on a reach, sailing between 90-130 degrees of apparent wind. It won’t take experienced sailors long to figure out that maintaining control with the 590-sq. ft. spinnaker in heavy breezes is no more difficult than on a big boat, and has a potentially bigger payoff.

Ross says his enthusiasm for racing small boats has been rekindled by this new generation of speedsters. “This boat can be easily crewed by two people,” he said, “but we usually race with four or six because with more than 10-12 knots of breeze she gets tippy and we need the weight on the rail to keep her flat.”

A typical sail inventory includes the 150-percent genoa, a 100-percent jib, main and 3/4-ounce spinnaker, a $3,000 to $5,000 expenditure depending on the type of sail fabric selected and the buyer’s relationship with a sailmaker. The main provides most of the horsepower. Permanent and running backstays provide the tools necessary to depower the main, but the good news is that the runners are primarily used to control sail shape and tension the headstay, so if the crewperson on the runners dozes off the rig probably won’t land in the cockpit. Depending on surface conditions, when the breeze exceeds is knots it may be time to change down to the 100-percent headsail to reduce heel and increase boatspeed.

Making hull speed going to weather in heavier seas will be the least fun aspect of sailing this boat. It’s sturdy enough, and the fine entry will alleviate some of the pounding, but a lightweight boat with low freeboard is a handful to steer and very wet, although the deep keel will make it a manageable pain.

Motor & Trailer

Dealers suggest that a 3-hp. outboard will power the Tripp 26 at 4 knots. You could use a larger motor, but who wants the extra weight? Aluminum mounting brackets are permanently attached to the stern, and the cockpit sole locker has space for a 3-gallon fuel tank.

Trailering the boat involves unstepping the tabernacle-mounted mast by attaching the tack of the headstay to a hook attached to the winch cable on the trailer and slowly lowering it to deck level. Ross has simplified the process by employing a spinnaker pole attached to the jib halyard and trailer winch, a system similar to that found on the Precision 23. Either way, it’s about a one-hour project. Total weight of the boat and factory trailer is approximately 3,650 pounds, which equates to 265 pounds of tongue weight.

Conclusion

We really liked this boat for a number of reasons, the most important of which is that it’s fun to sail, responsive in light breezes but stable enough that we’d be comfortable sailing to weather in a blow. The taste of off-breeze sailing we experienced whetted our appetite for another ride. Interior accommodations are adequate; it’s not designed for extended family cruising, but should be sufficiently comfortable for an overnight race crew.

The $29,900 price, FOB the factory, plus the cost of sails, is a fairly stiff entry fee to sail in fleets filled with moderately-sized boats. With only a few dozen sailing American waters, most owners will find themselves racing in homogenized fleets until one design fleets are organized. Actually, the boat is marketed at the lower end of the price scale for this new generation of boats, which includes the B-25 also advertised at less than $30,000, and the Melges 24 and J/80, both of which fly asymmetrical spinnakers on retractable bowsprits, and cost significantly more. Consequently, many sailors will face the historical trade-off between the expense of a state-of the-art hot rod, and used boats such as the Santa Cruz 27, Express 27, Hobie 33 and Olson 30, proven racers that sell for $10,000 to $30,000.