Photos by Bill Walker

Following graduation from California State Polytechnic University, naval architect Carl Schumacher spent four years working as an apprentice with Gary Mull before opening his own shop in Alameda, California, in 1977. He has since designed 37 boats ranging in size from one tonners to 50-foot world cruisers, participated in the design of the front-ruddered Americas Cup boat skippered by Tom Blackaller in the 1987 trials, and most recently designed the Alerion Express boats, which are being constructed at TPI Composites, Inc.

Design

The concept for the Express 37 was developed in 1984 by Schumacher and boatbuilder Terry Alsberg of Alsberg Brothers Boatworks in Santa Cruz, following several years building and racing the Express 27, a lightweight rocket that enjoyed tremendous success on the Midget Offshore Racing Association circuit. (See the entertaining transcription of Lighten-Ups white-knuckle ride in the 1983 Pacific Cup at http://express27.org/articles/squallbusters).

Schumachers objective was to design a boat that would excel on long ocean races that emphasize performance on reaching and running legs. It needed to meet the TransPac Race minimum size entry requirements, and also would have at least six feet of standing headroom.

To that end, he gave the boat a large, low-aspect main and small, high-aspect foretriangle that has come to be referred to as a masthead-fractional rig.

Helmsmen and trimmers find the design more forgiving to sail than a fractional rig. Because a hydraulic backstay is used to tension the headstay, running backstays are used primarily to shape the main.

The hull is defined by a fine, 18-degree bow entry that powers the boat through heavy seas when going to weather; a wide, powerful stern section; and V-shaped sections aft that produce a flat surface when heeled, a characteristic of L. Francis Herreshoffs designs. To concentrate weight amidships, the keel and mast were placed forward and combined with a balanced spade rudder. The ends of the boat are light and buoyant.

Though advertised as displacing 9,500 pounds, of which 4,500 is in the keel, Schumacher said that after construction, the standard version was weighed at 11,000 pounds and the MK II at 11,500 pounds.

The MK II cruising version has a 1-1/2-foot taller mast, shallower draft, and modified interior layout. In its standard configuration, the Express 37s sail area/displacement ratio (SA/D) is 20.64, and the displacement/ length ratio (D/L) is 168.

The first three hulls swept first through third place their class in the 1985 TransPac. A total of 65 boats were constructed, most of which are sailing in one-design fleets in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, on Long Island Sound and the Great Lakes.

By 1988, the company was also producing the Express 34, a scaled-down version of the 37, but building them too well, Schumacher said. By the time Alsberg discovered the boats were underpriced by $10,000, the company was floating in a sea of red ink, forcing it to file for bankruptcy.

Construction

The Express boats built by Terry Alsberg are as well built as any production boat anywhere in the world, Schumacher told us. Based on our inspections of boats that have been pounding across the Pacific Ocean and on San Francisco Bay for 10-12 years, wed agree with that assessment.

Like many Santa Cruz-based boatbuilders, Terry Alsberg, who headed up the boatbuilding operation, was schooled under the tutelage of the California building icon Ron Moore. The Santa Cruz boatbuilding scene during those days involved a lot of cross-pollination, and many of the elements you see in the Express 37 can also be seen in similar boats coming out of the region. A good example of what was going on at the time is the popular Moore 24, which Moore built by modifying a mold salvaged from George Olson (of Olson 30 fame).

For the Express 37, Alsberg combined a hand-layup with vacuum-bagging (a process in which vacuum pressure squeezes laminates to reduce resin-to-fiber ratio). The aim was to produce hulls that were consistent with the scan’tlings specified American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) and Lloyds Register.

After applying gelcoat to the mold, the base layer of 3/4-ounce mat was laid up using AME 4000 vinylester resins to prevent blistering, over which were laid three layers of 18-ounce bi-directional Cofab, except in the keel/sump area, where six layers were used. The hull was cored with 3/4-inch balsa. The outer skin has six laminations of knitted 18-ounce Cofab fabric. The deck is cored with 3/4-inch balsa with skins of 3/4-ounce mat and 18-ounce bi-directional Cofab.

Just 10 of the 65 boats built were the MK II model, and all of those are on the East Coast, most on Long Island Sound.

Structural support for the hull is provided by floors bonded to the hull and extending port and starboard to bunk height. The interior consists of two pans, one for the head and forepeak, another for the saloon and stern quarters. Additional modules, tabbed to the floor, form the galley stove/icebox arrangement, engine compartment, and the chart table.

The deck is joined to the hull on top of an inward flange, bonded with 3M 5200, and fastened with stainless steel screws on six-inch centers. Boats we inspected showed no signs of structural failures, despite years of racing. No signs of crazing or cracks were evident in the gelcoat, and the molded nonskid had weathered well.

Schumacher, however, pointed out to us some problems identified with early hulls.

The bulkhead behind the mast in some early hulls was glued to the keel floor with 5200. The bond flexed over time, so the bulkhead was retabbed with fiberglass that carried to the height of the berth, he said. Beginning with hull number 20, all bulkheads were bonded to the hull with a fiberglass tab.

A second problem was cracking on the 1/2-inch thick wood bulkhead, so the bulkhead was increased to 3/4 inch.

We also experienced deck cracks under the No. 1 sail track when class rules were changed to allow the use of Kevlar sails, said Schumacher. Because Kevlar sails don’t stretch very much, the boat did. To solve this, the track was reinforced with an aluminum backing plate.

A problem indigenous to San Francisco Bay boats was discovered after several sailing seasons. The hydraulic hose for the boom-vang exited the mast through a hole at deck level; after five to six years of use, several masts were discovered to have developed cracks in that area. In response, sparmaker Buzz Ballenger developed a sleeve to reinforce the mast section, and lead the hose aft through a watertight deck fitting.

To substantiate the claims of hull integrity, Schumacher recalled that one of the boats hit a whale on an ocean passage, and only bent the keel . . . Another ran onto the rocks at Alcatraz Island and was towed off by the Coast Guard, but only suffered a bent keel.

The owner of hull No. 23, who has raced the boat extensively, described being T-boned at the start of a race by a 55-foot, 40,000 pound boat traveling at 6 knots. I was certain, he told us, that the entire pointy end was going to be fractured. However, except for a small crack on the hull and three bent stanchions, the boat was not damaged.

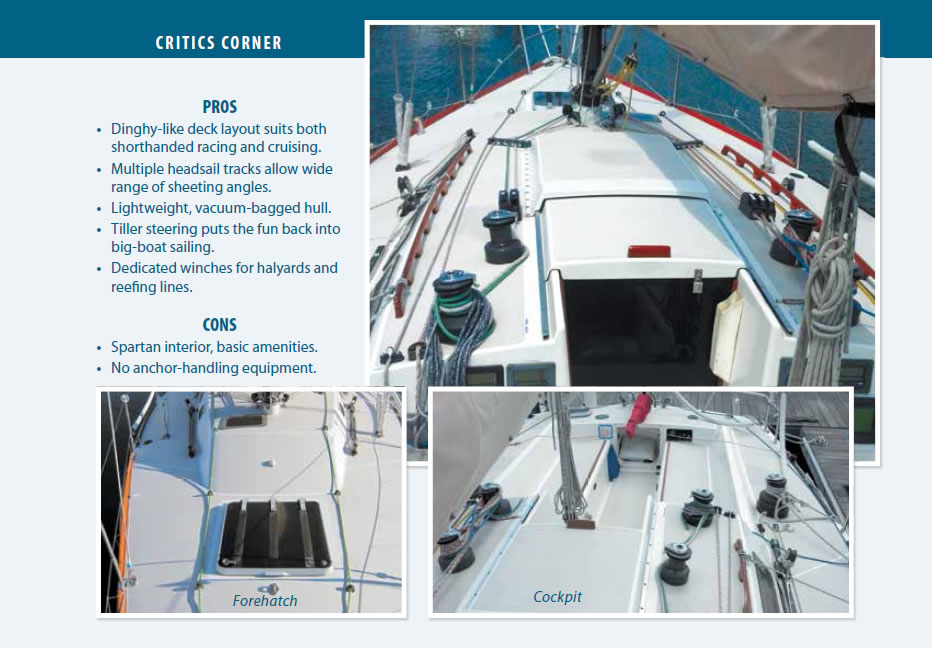

Deck Layout

From its inception, the deck arrangement and cockpit configuration were laid out with racing in mind. Owners using the boat for cruising purposes will find the boat easy to operate.

All halyards and sail controls are led through turning blocks to the cockpit where they terminate on the coachroof near the companionway. Halyards, cunningham, outhaul, topping lift, and foreguy are controlled by one person standing in the companionway, so there is no interference with the mainsail trimmer.

Genoa sheets are led directly from the Merriman sail track to Lewmar winches and cam cleats. By not leading the sheets through additional turning blocks, tacking is simplified and friction is reduced. T-track is mounted on the aft toerail for outboard jib leads and spinnaker gear; the toerail forward is teak.

In race mode, the cockpit positions the helmsman well aft of trimmers; the mainsheet traveler is just aft of the companionway, so it doesn’t interfere with trimmers and tailers. For cruisers, the cockpit has contoured seats that provide excellent back support as well as a comfortable radius under the knees.

The Ballenger mast is a tapered, anodized aluminum section supported by -6 to -12 Navtec rod rigging and double spreaders. The outhaul, with a 4:1 purchase, is housed in the boom.

Most boats were initially outfitted with tillers; however, several of the MK II models had a T-shaped cockpit with a 48-inch wheel. One owner retrofitted a 36-inch Edson wheel on a binnacle mounted about 2 inches from the transom. Because the entire aft end of the boat belowdecks is open, the retrofit was accomplished with relative ease.

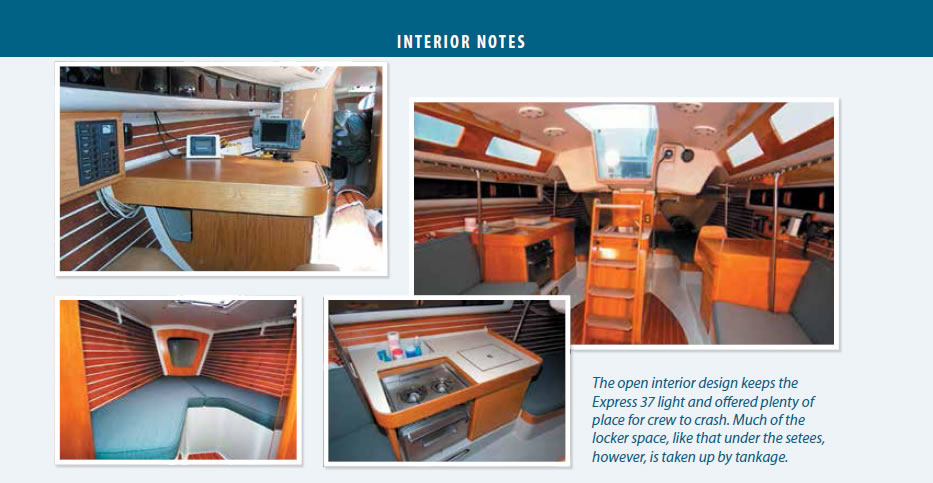

Belowdecks

Though designed to sail fast, Schumacher tried to create accommodations below that would be comfortable for an offshore crew. He engaged a client, M. Fillmore Harty, a prominent furniture designer for whom he had designed a boat, to assist with design of the interior. Though it will not be confused with a traditional teak-laden cruiser, it provides comfort. Oak cabinetry, ash window frames, a teak and holly sole, and teak warming strips spruce up an otherwise plain interior.

A wooden table hinged on the main bulkhead provides seating for four to starboard, and a port settee doubles as a berth. Water and fuel tanks occupy space below the settees that would normally be used for storage. That lack of storage area is offset by unique, aircraft-like overhead storage compartments that line both sides of the hull, providing stowage behind sliding Plexiglas doors.

On the standard models, the galley consists of a stove and ice box to starboard of the companionway. A double stainless steel sink atop the engine compartment is directly below the companionway ladder.

Theres little privacy in the aft section of the boat, which is wide open with pipe berths situated on each side of the hull. The area is ventilated by two opening ports in the stern. Visible in this area is a fiberglass tube glassed to the hull for the man-overboard pole.

This configuration does allow 360-degree access to the engine compartment, the aft end of which doubles as a hanging locker. This aft area is partially finished with teak strips, though the last three inches of hull is exposed gelcoat.

The MK II is a more cruiser-friendly version. The galley is a U-shaped affair and in lieu of the wide open pipe berth in the port quarter, there is an enclosed stateroom with a double berth.

The saloon has a nav station with a chart table large enough for the serious navigator, five drawers for storage, an electrical panel with six circuit breakers, and space for basic instruments and gauges. Though wiring runs are inconspicuous, they are easily accessible behind the nav station and settees.

The head is located to starboard behind the main bulkhead; it is Spartan, with sink, toilet and sump for shower. All plumbing is exposed. A second hanging locker is opposite the head.

The forepeak contains a V-berth for two adults, though it also lacks creature comforts like reading lights and shelving. There is storage below the berths.

We think spaces belowdecks are adequate for racers or cruisers, though cruisers will no doubt prefer the MK II version and may want to locate a carpenter to improve the aesthetics of the head.

Performance

The boats racing records in the rugged conditions of San Francisco Bay and its successful record in long distance ocean races, attests to its performance and durability. It has proven fast going to weather under full main and No. 3 jib in typical summer conditions on the bay, where wind speeds are predictably 15-25 knots, and in the lighter air conditions of Puget Sound where the masthead rig outperforms fractionally rigged competitors. Sailed properly, the Express 37 sails to its PHRF rating of 72-76 in most areas.

We tested a standard model on a 40-mile race on Puget Sound, sailing with a crew of seven. Though the boat struggled in light winds, it managed to maintain a modicum of boat speed while carrying a 3/4-ounce chute. An attempt to improve boat speed by flying an asymmetrical spinnaker flown from the jib tack was unsuccessful. When the wind piped up to a steady 12-17 knots, it easily carried a 140 percent genoa through 2- to 3-foot swells without excessive heel. She has a wide sailing groove, and rewards the skipper who feathers up in puffs. Sailing downwind in the same conditions, the boat held steady at 9-10 knots.

Conclusion

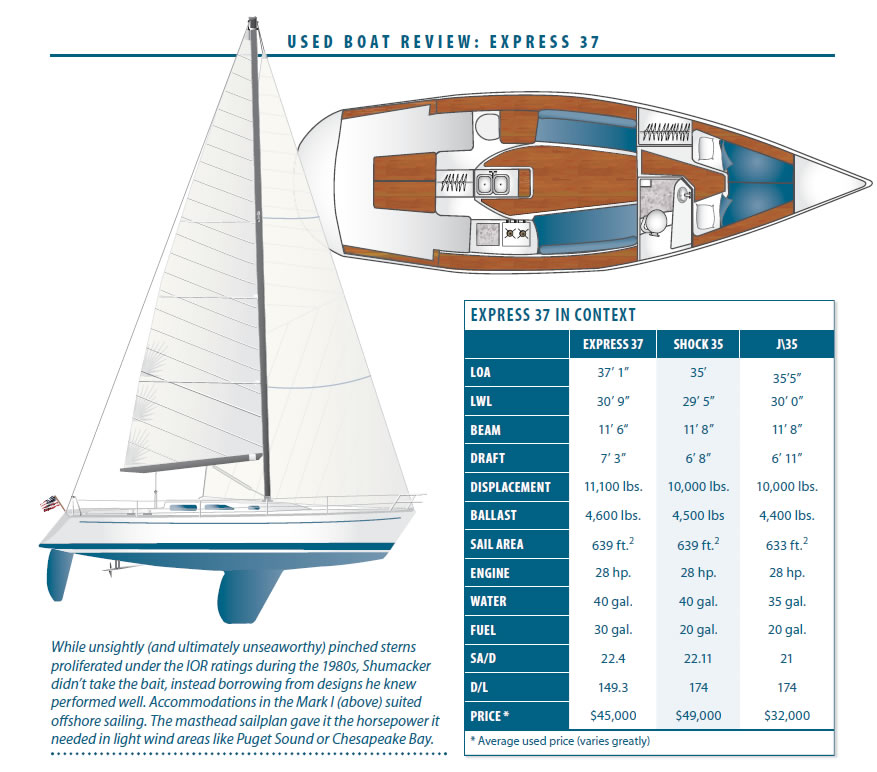

We think the person looking for a used 35-40 footer in the performance category should give careful consideration to the Express 37. Racers interested in moving to a bigger boat will find one-design fleets in many areas, or may compete with J/35 and Schock 35 types in PHRF.

The boats are well constructed, hardware is well laid out, and the sail plan excels through a wide range of wind directions and velocities.

Because these boats have primarily been sailed in racing fleets, a buyer may find a used boat equipped with a larger than average sail inventory, as well as electronics, although these may be outdated.

The downside to the Express 37 is that the interior lacks the privacy of a conventional cruiser. Its accommodations are larger than those of the Schock 35 and J/35, but not as well appointed as the Schock. You buy this boat first for performance, because you like a fast, well-constructed boat that handles well.

The Express 37 sold new in 1988 for $85,000, plus sails and electronics. Typical used boat prices run roughly from $45,000 to $60,000, comparable to the J/35 and Schock 35.