The Freedom 30 grew out of something called the “Freedom Philosophy.” Getting its start somewhat significantly in the Bicentennial Year of 1976, this philosophy has several tenets. One of the most arresting is: “They did away with wires on bi-planes half a century ago. Why do we still need stays to keep our sailboat masts flying?”

That philosophy was developed and broadcast by Garry Hoyt, a Finn dinghy racer who was struck, sometime in the mid ’70s, with a yen to go cruising. Hoyt found that the boats available to him all entailed unacceptable amounts of effort, complication, and unfulfilled promise. What he wanted was “sailing fast without mazes of stays, passels of deck apes, and piles of jibs,” and what came out was a wishbone-rigged cat ketch of his own design. Christened the Freedom 40, the new boat took simplicity so far that she was offered with a sweep oar instead of an auxiliary when Hoyt founded Freedom Yachts in 1976.

Oar power didn’t go over, but for the better part of the next decade Hoyt, whose first career was in advertising, designed, argued, and innovated his company into the spotlight. Smaller Freedoms like the 33, 32, 29, and 25 came along. All were shaped by the same insistence: “It is possible to go very fast, indeed, even without crew or complication, if you have a boat that is designed for the purpose.”

Experimentation with rigs like the cat schooner and achievements like the gunmount system for singlehanded spinnaker sailing spiced the argument. Over the years both the philosophy and the boats it inspired found their share of takers. But there were problems. First of all, Hoyt was running out of converts. Says fellow designer Bob Perry: “You can always tell the pioneers.They are the guys with the arrows sticking out of their backs.” Aesthetically, Hoyt’s early boats were “a matter of taste” at best. The original Freedom 40, in fact, looked something like a galleon. Some people liked it, but it was very different. Then, hassle-free sailing was fun, but was it worth a price premium? And not all the boats performed superlatively; some were tender and all were underpowered in light air.

Far from abandoning invention (Hoyt is now the principal of Newport R&D) Hoyt simply sold out to Everett Pearson of Tillotson-Pearson Industries (contract builder of the Freedoms).

Design

The new management picked Gary Mull to do their first boat. A Californian whose race record (Munequita, a Ranger 37, first overall in the 1974 Southern Ocean Racing Conference; custom boats like Dora, Improbable, and La Forza del Destino; hot classes like the Ranger 22, 23, and Santana 22) was among the best, he was also a graduate of the Sparkman & Stephens office and designer of fast cruisers like the cold-molded Hot Flash and the Santana 37.

It’s interesting to contrast Hoyt’s “punch a hole in the envelope” mentality with Mull’s approach: “While designing racing boats I have never seen any reason to be particularly conservative and had no qualms even about designing the double-ruddered, keel-less USA [for the Golden Gate Syndicate] to try for America’s Cup. But for cruising boats intended to go wherever their crews will take them, moderation is the watchword.”

Mull’s first Freedom was the F-36. She retained the basic elements, but she edged a bit toward the moderate; toward “normal” looks and “expected” performance-cruiser capabilities. Mull (a non-smoker who died of lung cancer at age 56 in 1994) wrote in his design commentary, “We agonized long and hard about whether she was a cruiser/racer, a racer/cruiser, or what. Finally it came to us: ‘Why don’t we just call her a boat?'”

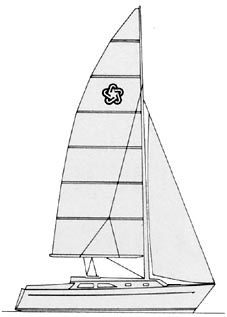

The Freedom 30 was a follow-up to the 36. The family resemblance is strong, and pillars of the Freedom approach, such as a freestanding spar, cockpit-centered controls, a vestigial jib (tamed via the self-vanging “CamberSpar”), and a dead-even balance between a daysailing cockpit and a cruising interior, are evident in both boats. Some of the differences between the two stem from their difference in size, but many of the design refinements form an interesting indicator of how Mull increased his skill at suiting the Freedom ideal to the realities of wind and wave.

The F-30’s light-air performance, for instance, is better than her big sister’s. Begin with an increase in the sail area/displacement ratio from about 19 for the F-36 to about 20 for the F-30—not a huge leap, but that sail area was put into a big roach near the top of the sail, where it benefits from the healthiest airflow. The F-30 also has an appreciably sharper entry angle, and a more efficient sail area/wetted surface ratio.

Freedoms are at their best in a breeze. The F-30 gets good stability from a generous (a bit more than the F-36) beam/length ratio and from a ballast/displacement ratio of 41 percent (3,150 pounds of lead). The long, relatively low-aspect ratio keel keeps the center of gravity from being as deep as it might be with a deep fin, however. The boat is stable, but we would hesitate to call her “stiff.” Yet the bend of the carbon fiber spar plays a large part in depowering the main and most of the heeling force is concentrated in a single sail; this renders her quite sure-footed. None of the many sailors reporting to us felt it necessary to reef in winds below 20 knots.

Mull used the classic aesthetic elements: stem, stern, and sheer lines; house front and roof angle; freeboard, and mini-counter to keep his 30-footer from looking as chunky as a tri-cabin cruiser might. At the eye-catching center of the design are her big house windows that serve to direct your gaze fore and aft and make the boat look lively. It wouldn’t rate a mention today, but in 1984 when naval architects were just starting to wring full power from their computers, Mull talked about using his computer design program to fair lines and create full-sized lofting, to deliver CAD renderings of essentials like the keel and rudder, and to run performance, helm balance, and steering evaluations. Whether it came from the computer or Mull’s own calculation, the designer eased the F-30’s center of lateral resistance aft a good five percent of waterline length in relation to where it would be on a standard, sloop-rigged performance cruiser. That subtle shift makes the boat (essentially a catboat) harder to spin into the wind—i.e. it reduces weather helm.

As Jim Donovan, a protégé of Mull’s, concluded, “Probably the most important thing I learned is that just the right, and sometimes very subtle, blend of the yacht’s characteristics will yield the better design.”

In the midst of the production run, Freedom added a two-foot swim platform to the transom and called the boat the new Freedom 32. The platform, which adds some dynamic waterline, is the only difference, and Freedom 30 owners today can retrofit their boats with the platform. This 32 is not to be confused with an older Freedom 32, a Garry Hoyt design with a cabin trunk that extends right aft into high cockpit bulwarks.

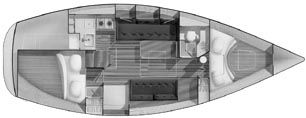

Accommodation

The Freedom 30’s interior gets high marks. Wood is used judiciously. The ash ceiling strips lighten the cabins nicely. The aft double is not palatial, but it’s serviceable, private, and surprisingly well-ventilated. One sailor complained that the saloon double is big enough for “only one and a half small people.” The berths in the other cabins, however, are larger. A nav station on a 30-footer is often awkward or useless. Mull achieved a workable, realistic space with the stand-up area (30″ x 24″) right by the companionway, which makes communication with the cockpit relatively effortless.

The ice chest keeps ice for three days in the tropics, thanks to its 4-inch insulation. Reaching into it, however, entails leaning over the stove. The pass-through trash bin was one of the first of its type, and works well unless you allow sloppy trash-passing, in which case there can evolve a smelly mess in the cockpit locker, where the trash can is shock-corded against the aft face of the galley bulkhead.

Lined and louvered lockers, rounded corners, and well-placed fiddles show real thoughtfulness, but prior to 1987, interior grabrails weren’t standard.

The head is inconveniently close to the hull side and the sink drain empties (without a seacock) at the waterline. We hear that the optional shower “works fine,” but there’s no surplus of elbow room lavished on the head compartment. The bilge sump, however, is deeper and more capacious than average. The shower sump (with its embedded pump) is a nicety that didn’t survive more than a year or two on most boats.

Despite the large fixed windows, ventilation for head and cabin is adequate via nine opening ports and three hatches. Headroom was originally published as 6′ 3″, but is a bit less than that—still very good for a decent-looking 30-footer.

Construction

The hull and deck of the Freedom30 are cored with end-grain balsa (making her quiet under sail and helping to minimize condensation). The fiberglass laminates on either side of the core are built primarily of mat and 24-oz. roving using polyester resin. Where local reinforcement is called for, it was generally done by adding mass with 1.5-oz. “Stitchmat.” Solid glass was used in the stem, the keel stub, and below the turn of the bilges. Areas for mounting hardware and at the hull/deck joint are also solid. The boat was among the first to have a composite rudder shaft. That eliminated corrosion and allowed precise engineering and material control in this high-load area. The rudder has two bearing points, one in the hull and the other in the short, vertical, “mini-skeg” that joins the upper fifth of the big blade. Responsive steering is one of the F-30’s strongest performance points; the rudder assembly has proven durable and trouble-free.

The free-standing spar is a Freedom hallmark. Tillotson-Pearson built the masts for the 30 using mandrel-wound carbon fiber, E-glass, and epoxy resin. We suspect that the original lifetime guarantee issued by Hoyt was a means of deflecting buyer hesitancy over this pioneering feature, but the spars have, in fact, performed extraordinarily well both during inshore competition and during offshore passages.

The hull-deck joint consists of an inward-turning flange on the hull. The deck is bonded atop that with 3M 5200 sealant, and the parts are locked by through-bolts on 6″ centers, joining hull, deck, and slotted aluminum toerail. It’s a time-honored system, and it works well.

Dave Pugsley, former marine director of the Bitter End Yacht Club in Virgin Gorda, and thus custodian of the fleet of F-30s raced hard and used year-round for more than 15 years by that resort, said, “The hull/deck joints never leaked at all . The only problem we had with the hulls was a bit of leakage around the through-hull fitting in the head, which we then fitted with a seacock. Some people also complained of leaks around the opening port in the galley.

“The biggest problem we had with the boats was deterioration of the mast retention system over time. That allowed the masts to rotate slightly, but we found that stiff mast wedges were a good cure.”

The boat’s aluminum fuel tanks have been something of a problem. Eventually, pin-hole leaks can develop where the prop shaft mounting bolts bear on the bottom of the tanks. Said Pugsley, “We just took the old tanks out, built small shelves, and put new tanks onto the slightly raised beds. It wasn’t as tough as it sounds.”

There appear to have been varying degrees of clearance between the shaft coupling and the stern tube. In the Bitter End fleet, after replacing the flax packing in several stuffing boxes after years of wear, Pugsley decided to replace the stuffing boxes entirely with PSS Shaft Seals. These “packless” glands from PYI (www.pyiinc.com) worked well.

“Another sore spot was the stop cable for the engine,” said Pugsley. “It came mounted at a 45-degree angle on the engineroom bulkhead, and thus it retained moisture and corroded quickly. Simply mounting it in a vertical position was the cure.

“In addition to being easy to cruise and great fun to sail, the boats are well-built. Call it ‘the ultimate testimonial’—I bought one myself.”

Performance

There are some definite plusses to the unstayed rig. It lets you, for instance, position the mainsail where it should be when you’re headed downwind, rather than being limited by the shrouds.

Freedoms sail well by the lee before jibing. When you do jibe there’s a sort of an “airbrake” effect created by the large roach. Rather than slamming lethally across the boat, the full-battened main is quite docile in shifting sides. Certainly most sailors enjoy the freedom from grinding winches, the superior maneuverability and visibility offered by a small jib, the self-vanging “whisker action” provided by the CamberSpar wishbone, and the convenience of truly being able to “do it all” from the cockpit.

The big main can seem very heavy to hoist. Says Pugsley, “We found that rather than fitting any special cars, the sail slide solution developed by Haarsstick worked best at taking the work out of raising the main.”

Gooseneck straps are a fragile item. After breaking several by letting the boom swing too far forward, the fleet at BEYC installed boom limiters.

Says one couple who sailed a C & C 30 for years, “With our Freedom 30 we miss the big headsail upwind and in light air, but we sail faster and more often (and with less strain) in our new boat.”

With the close sheeting angle for its jib, the F-30 is surprisingly close-winded, and since she’s so easy to tack, going to weather is no chore. On the other hand, she will never do as well in light air and chop as a similar boat with a powerful overlapping headsail. “The boat has a fairly wide groove,” says Pugsley, “but you can’t pinch her. She’s got to be sailed freer than a conventional boat. She’s so easy to tack that on a short course she can do well against PHRF competition.”

When the breeze comes on, attention needs to be paid to the big main. “If you attempt to drive off without easing sheet and traveler, you’re definitely fighting City Hall,” one racer reports. “But the bend in the mast means that the main delivers lots of usable power without reefing or putting the boat on her ear. On the wind in big waves she’s at her worst, but no matter what the wind strength, she’s a reaching and running machine.”

Despite being crammed rather tightly into the engine box, the Freedom 30’s Yanmar 2 GM 20F diesel receives great reviews. Says Pugsley, “We had no significant troubles with them season after season. Access is good with the engine box removed, but the box itself is tighter than average. The standard two-bladed prop wasn’t quite as robust as I wanted, so I replaced it with a three-bladed on mine and don’t feel that sailing performance suffered significantly.”

Consider the oversized, comfortable, uncluttered cockpit, turn-on-a-dime steering, and effortless short-tacking, and you can begin to see what Garry Hoyt got so excited about.

Conclusions

It seems on the surface that the Freedom 30 was part of a movement from the radical simplicity and mind-opening territory staked out by Garry Hoyt toward a more conventional middle ground. She has proven popular and successful. We would suggest that is because, on closer examination, she is not so much a product of developments in philosophy, but rather a creation of Mull’s brilliant design evolutions and Tillotson-Pearson’s solidgrasp of what makes a valuable boatand how to build one.

Production of the Freedom 30 and platform-enhanced 32 ran to 126 hulls. The original price of the 30 in 1986 about $60,000. As of July ’03 there are two 30s listed through the brokerage links at www.yachtworld.com, one for $48,900, the other for $47,500.

There’s an informative message board devoted to Freedom owners on the Freedom Yachts website.

Contact – Freedom Yachts, 401/848-2900, www.freedomyachts.com.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Freedom 30 Owners’ Comments.”

I searched under “Freedom 30 cat ketch”. I do not think this boat qualifies!!