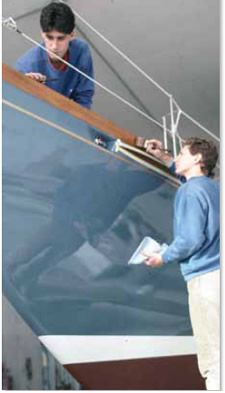

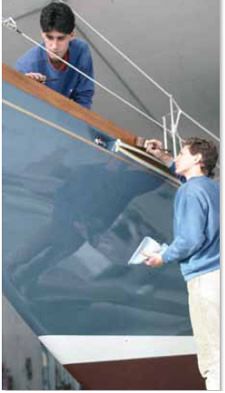

Photos by Ralph Naranjo

The lure of sailing is a magnet that draws us toward boat ownership, but annual maintenance, system shut-downs, and costly refits are a less-welcome fait accompli. To ease the boat-maintenance burden, Practical Sailor regularly shares technical tips and how-to strategies that guide the do-it-yourself (DIY) boat owner through a wide range of projects. Self-sufficiency will always be our emphasis, but we have also noticed that fewer recreational sailors have the time, training, or the inclination to roll up their sleeves and tackle the big jobs.

A common thread among this growing group of do-it-for-me sailors, is the desire to become a smarter consumer of the services offered by a very diverse marine industry. Whether its shopping for a cost-effective annual haulout, with an annual bottom paint job and topside compound and wax, or picking the right source for a major refit, price and proficiency are on every consumers mind.

So, in an effort to cut through the hype and navigate the spin, we offer a Practical Sailor perspective on how to pick the right boatyard and contract quality work. In short, we offer readers more input on how to make cost-effective maintenance decisions.

The first of our golden rules is to beware of labor rate-based evaluations. Hourly rates are a poor yardstick with which to measure value. Despite the fact they range nationwide from about $35 per hour to $100 per hour, they should never be used as the sole means for choosing a service provider. At the bargain-basement end of this range, we came across a yard that had charged a client thousands to fix a charging/starter problem that never did get resolved. The final straw came when the boat owner was told that the vessels wiring was worn out and needed to be completely replaced.

He hired a systems expert who asked the yard manager what was meant by worn-out wiring? Was the insulation frayed, the stranded copper oxidized, or the connectors corroded? No, responded the manager, the copper had lost its ability to efficiently conduct current. What the consultant did find was a mis-wired alternator and enough connector corrosion throughout the electrical system to raise resistance and account for the charging problem and intermittent starter woes. In this case, the bargain $35 per hour labor rate was anything but a good deal.

As a prior boatyard manager and author of the book Boatyards and Marinas, I don’t buy into the idea that most boatyards are out to dupe their customers, profit on the innocent, and send piles of cash off to banks in the Cayman Islands. Few boatyard owners summer in Sardinia or have a lavish yacht that is the envy of their customers. And when it comes to scandalous profiteering, Madoff, Boesky, and the London Whale still get top billing.

What is true, however, is that boatyard owners have a high overhead, and many of the jobs that they tackle are labor intensive. Add in high real-estate prices and costly regulatory stipulations, and its no surprise that more and more complex systems aboard medium-sized boats have caused invoice shock along the waterfront.

Estimating Costs

Savvy sailboat owners need to develop a sense of what might be called the all up costs and understand how to keep them under control. These ownership expenditures may kick off with the purchase price, but also include many incremental costs along the way. Some, like insurance, are annually repeating cash commitments, but others involve systems wearing out, or the addition of equipment we just can’t do without.

Budgeting for future refits and repairs should be part of a sailors long-range plans. In the gilded age, when sailboats were varnish farms and owners wore linen pants, yachtsmen expected to pay 10 percent of the original purchase price of their boat annually on slippage, mooring fees, and maintenance. The advent of molded fiberglass hulls and the disappearance of bright finished woodwork have lessened some of the work load, but system complexity and increasing labor rates have kept the numbers behind the dollar sign rising.

Theres no question that a slightly smaller boat, one thats more Spartanly equipped, will help to lower yard bills. So too, will the purchase of a previously owned sailboat thats in like new condition rather than one in need of repowering, re-rigging, and a systems makeover. Avoiding the lure of teak and mahogany, and doing without high-energy creature comforts, go a long way toward taming the yard bills. Little things, like using ablative coatings and avoiding bottom paint build-up will eliminate, or at least postpone, the need for costly paint stripping in order to remove the accumulated, flaking residue.

So, for those not inclined to call maintenance part of the pleasure of sailboat ownership, we spoke with boatyard pros and looked over facilities around the country. It became clear that good yards are under-pinned by a capable staff, and whether its the Driscoll operations in San Diego, Dave Irishs yards in Michigan, Jack Brewers chain of 20-plus boatyards in the Northeast, or the old David Lowe operation in Stuart, Fla., thats now owned by Hinckley-all have competent personnel as a core feature of their success.

As the boatyard business model evolved, customer service has moved to the forefront. When I recently interviewed Max Parker, operations manager at Zimmerman Marine in Maryland, he was quite candid about how clients and boatyard interactions should proceed. According to him, the dialogue with customers is ongoing and becomes more specific with time. The starting point is a discussion of the owners priorities and his or her fix-it wishlist.

The Zimmerman crew prefers to do a survey of the vessel and have a good feel for the overall condition of the boat and its specific strengths and weaknesses. When the owner better understands what the inspection has found and what the yards experts believe are the most pressing problems, the dialogue moves from rough estimates toward firmer quotes. Thats when job scheduling can proceed.

The value of the survey really comes into play in situations like when an owner has budgeted for a new freezer and bow thruster but the staff has noted that the standing rigging is at the end of its lifespan and the mast heel and step are badly corroded. They inform the owner of the potential structural problem and its safety overtones. Plans for the freezer and thruster may proceed anyway, or the refit agenda may be altered to focus on rigging. The yard is also happy to schedule both jobs.

The key takeaway here is the value of a yard survey, comprehensive knowledge of each clients boat, and a proactive boatyard staff. Without this input, an inexperienced boat owner can suddenly find himself with the most comfortable, prettiest boat that isn’t fit to clear the sea buoy.

Haulout Equipment

Every boatyard experience begins and ends with hauling and launching, and the quality and kind of equipment thats used says a lot about the operation, but the crew doing the work says even more.

The familiar blue Marine Travelift, or one of the knockoffs (also painted blue), are equipped with adjustable polyester slings that grab the hull in at least two areas. One strap contacts the hull just forward of the rudder, and the other nestles in just forward of the keel. Properly set up, the lifting loads pull slightly toward the center of the boat rather than coax the slings to slip off the ends.

A good operator knows how to keep the aft sling clear of the prop and shaft and the forward sling close to the keel. A line between the two slings makes sense, and as its being tied, the operator glances to make sure that the speed impeller has been withdrawn and a dummy plug inserted in its place.

Travelifts range from 15- to 500-ton capacities, and on the larger lifts, the number of slings and their rated safe working loads increase dramatically. Every sling, regardless of Travelift size, should be power-sprayed between haulouts to remove the previous boats, barnacles, slime, and smeared paint. Though it may be harrowing for a new boat owner to see his boat dangling in the air, the Travelift ride is the most secure ride in the business.

This doesn’t mean that a marine railway or a crane is not appropriate for hauling and launching sailboats. It just means that the people operating this equipment better be good at their jobs. Cranes that use slings to haul boats should be equipped with spreaders or a steel frame that keeps the slings from putting excessive compression across the hull and deck.

The bulkhead where a crane perches during a heavy haul must be engineered to handle the combined weight of the boat and crane. A marine railway is usually a safe and reliable means of hauling and launching, but its a time-consuming process that often is tide dependent. If there are equipment options in your area, its hard to beat a Travelift.

A key rule of thumb is that its never wise to be the largest, heaviest, or deepest draft vessel in the yard you choose. Recreational boatyards normally use good equipment, but regulations mandating specific maintenance, cable replacement, and even tire lifespan are minimal. Heavy equipment such as cranes used in urban construction are tightly regulated, but the same equipment operating in most boatyards doesn’t face the same scrutiny. The boat owner with the biggest boat is likely to be the annual load test for his boatyards lift.

Equipment maintenance and cosmetic appearance is another telltale in the yard-evaluation process. And its not just the Travelift tires and the cables and slings-all of which should be in good condition-that tell the story. Just as crucial is the pier that the lift drives out on in order to straddle your boat.

The H- or U-shaped heavy gauge steel that Travelift wheels run in should be relatively rust-free, and the pilings, often a straight and batter-pile combo, need to be load-bearing and free from rot, splitting, or other signs of deterioration. A brand-new lift wont solve the problems of a decrepit pier. All too often, the best bargains in boat hauling are found at the yards with the lowest investment in hauling hardware. I feel that efficient, well-run yards with good gear can come pretty close in price, and the small savings and elevated risk linked to opting for the former is not a bargain.

The shops should mimic the same good maintenance appearance of well-tended lifts and piers. However, a skilled boatbuilder friend of mine would get nervous when his shop got too clean-it simply meant that his crew was short of boats to fix or build.

Close scrutiny also pays off when you look over an operation and marvel at the quality of workmanship. Make sure that what you see is the kind of work youll need on your own boat. For example, a crew of highly skilled ships carpenters may be able to create magic with wood, but if the balsa core is wet and rotted in the foredeck of your fiberglass-reinforced plastic (FRP) sloop, the shipwrights joinery talents are not your solution. Today, the FRP guru and the paint-and-gelcoat maestro are the lads that are in high demand-along with the ever-engaged mechanics and electricians.

Types of yards

Boatyards are quite different from automotive service centers, and for ease of comparison, we have broken them up into three distinct categories. The first grouping is a cluster of facilities that can haul and maintain vessels up to-and in some cases, over-100 feet in length. Some also have a significant following of sailboats in the 40- to 55-foot range, whose owners are looking for top-tier turnkey maintenance and rely on the highly diversified skills at top-of-the-line operations.

Big yards like Newport Offshore, Hinckleys operation in Portsmouth, R.I., and Thunderbolt, Ga., and the prototype, Rybovich of West Palm Beach, Fla., epitomize the platinum plan of yacht maintenance. But what they have also done is set standards in craftsmanship and customer relationship that have trickled down to smaller, less-expensive operations.

The next grouping includes well-capitalized modern facilities that may exist as standalone operations or as a network of regional facilities under single ownership. They cater to the mainstream boater in a given area and may occupy municipal land or represent a private enterprise. The common thread is good-quality hauling equipment and either a skilled staff on hand or a cluster of sub-contractors affiliated with the yard.

The upside of the fully staffed yard is that the yard manager you deal with has full oversight of the work being done on your boat. In the case of the outside-contractor model, you become a nautical general contractor and work out your own arrangements with each subcontractor. There are upsides and downsides to each.

The third grouping is boatyards that tend to be from the old school and are as good or bad as the characters that run them. Around the world, youll find watermen who have come ashore, engineers with a hands-on calling, and boat builders who need haul-and-launch capabilities. There are no generalized rules that cull the good from the bad. It requires a close look at each one individually, and in most cases, there is value to be found in cultivating a relationship with a small-business rendition of a boatyard. See what others who have used the facility for a while have to say, and try to find others who have gone elsewhere and ask why. The priorities we stress are sturdy, safe hauling capacity, and skill in the services you will be using.