Darrell Nicholson

Summer is here and the time is right . . . for testing your squall-busting tactics.

The comparison of jibe-taming devices in the July 2017 issue of Practical Sailor is an appropriate topic for the summer when afternoon squalls so frequently add a little excitement during the leg back to the marina, or the approach to the next anchorage.

A tempting response to the sudden increase wind that accompanies a squall is to ease sheets and run before the wind-flatten the boat out and ease the flogging sails. However, the danger in running before a squall (or tacking downwind, a tactic sometimes employed by offsore racers) is the inevitable wind shift that can cause an accidental jibe. Since squalls are usually short lived, with the strongest winds lasting less than 20 minutes, simply reducing sail to a safe configuration and motoring through is a less taxing approach. What is a “safe” configuration? Gusts much over 40 knots are not common, but some devastating downbursts in excess of 50 knots can occur in volatile areas. (The fatal squall line that struck the fleet in the 2011 Chicago-Mac race is a good example).

The ideal sail plan for dealing with squalls will vary by boat, visibility, sea conditions, and intensity of the squalls. Ideally, the helm is still relatively well-balanced and responsive for whatever point of sail you choose. A moderate amount of of weather helm ensures the boat won’t be be overpowered in a gust. Lee helm is to be avoided. Same for excessive weather helm. If you’re carrying a mainsail (presumably well-reefed), ease the traveler and be ready to ease the sheets.

At night, when squalls can sneak up on you with little warning, the most conservative approach makes sense. Our gaff-rigged ketch reefed down with a double- or triple-reefed main and staysail could handle about anything and still keep moving on squally night, but our main was easy to scandalize (dip the gaff) if the gusts were particularly intense. On a conventional a Marconi rig, it is not so quick and easy to reduce the area of the mainsail without flogging. However, if you’re working to windward in daylight, a well-reefed (double or tripple-reefed) full-batten main can be feathered through a moderate squall with very little flogging as you motorsail.

When reaching or sailing further downwind, a common approach here in Florida is to motorsail with only a reefed. roller-furling headsail (preferably a staysail) which is kept up mainly to steady the boat when there’s a sea running. (The headsail be balanced with a reefed mizzen on a ketch.) One caveat to the headsail-only approach is that if you have a masthead sloop with a big 135-150 percent genoa, the furling gear needs to be reliable. The last thing you want is for the furling line to part and this sail to fully open and start flogging during the peak gusts. Better to endure a little rolling while motoring under bare poles rather than risk a shredded a sail.

On a short-handed boat, dropping all sail and motoring is the most conservative approach, and makes sense when a particularly nasty squall line threatens.

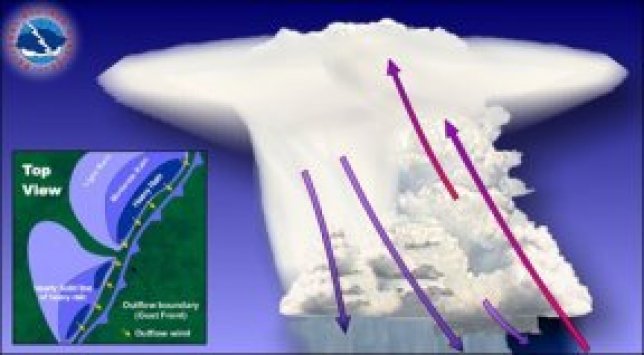

While every squall is different, there are a few rules of thumb that can help guide your decision-making process. The following bits are culled from my own experience and a couple of weather books Ive found helpful over the years, Bill Biewengas Weather for Sailors, and David Burchs Modern Marine Weather. Burchs book has some handy illustrations showing the direction of wind flow around a typical squall. Id be interested in learning the titles of other books that cover squall tactics in detail-most seem preoccupied with hurricanes and winter gales, storms that the average sailor rarely encounters.

If you are the type who benefits from seminars, look for those offered by former NOAA forecaster Lee Chesneau (www. marineweatherbylee.com), author of Heavy Weather Avoidance.

Squall Tips

Keep in mind, there are plenty of exceptions to these rules of thumb-but as Burch puts it, you have to start somewhere.

- Taller clouds generally bring more wind.

- Flat tops or boiling tops can bring brisk wind speeds and sudden wind shifts.

- Slanted rain generally indicates there is wind. Squalls often move in the direction of (or sideways to) the slant, so don’t assume that the cloud is dragging the rain behind it, as it might appear.

- Track cloud/storm movement by taking bearings on the center of the storm (not the edges).

- Watch for whitecaps below the clouds, indicating strong gusts.

- Tilted clouds often bring wind.

- The first gust, usually a cool downburst, can strike one-to-two miles before the cloud is overhead, and before the rain starts, so reduce sail early.

- The strongest gusts and the increased wind accompanying the squall generally blow in the direction of the cloud movement, i.e. outward from the front of the cloud. However, increased wind blows outward from all sides of the cloud.

- Squalls do not necessarily come from the direction of the mean ambient wind, so squalls to weather are not the ones to worry about. It is the ones to the right of the true wind, about 30 degrees, that are headed toward you (i.e. if a southerly wind is blowing, it is the squalls to the southwest to watch for).

10. The strongest wind comes with or just before the light first rain. If the squall arrives already raining hard, the worst winds are usually past, but strong gusty winds are still possible.

11. Behind any squall is a unnerving calm.

12. If you are faced with a number of successive squalls, they will often follow a predictable pattern, allowing you to fine-tune your tactics.

13. If you plan to bathe in the downpour, go easy on the shampoo-you might not get enough rain for a rinse.