There are a number of ways to attach a snubber to an anchor chain. A gripping hitch, a soft-shackle, or a chain hook are the most common. Of the three, Practical Sailor has a strong preference for a camel hitch or similar gripping knot (see PS August 2009 online), but for the many who seek a faster, simpler way to attach a snubber, here is a look at chain hooks.

Chain hooks come in a variety of designs, but most could be categorized as either a hook or a claw. Like knots, cleats, stoppers, and safety tether hooks, chain hooks present a maddening design challenge because the tasks they are expected to excel at-gripping and releasing-stand in stark contradiction.

Chain hooks used for anchoring are primarily derived from hooks used widely in the lifting industry. Their most common use is to shorten chain when lifting. The hooks sold by marine manufacturers and suppliers present few, if any, design changes, except that marine versions come in stainless steel or with galvanized coatings.

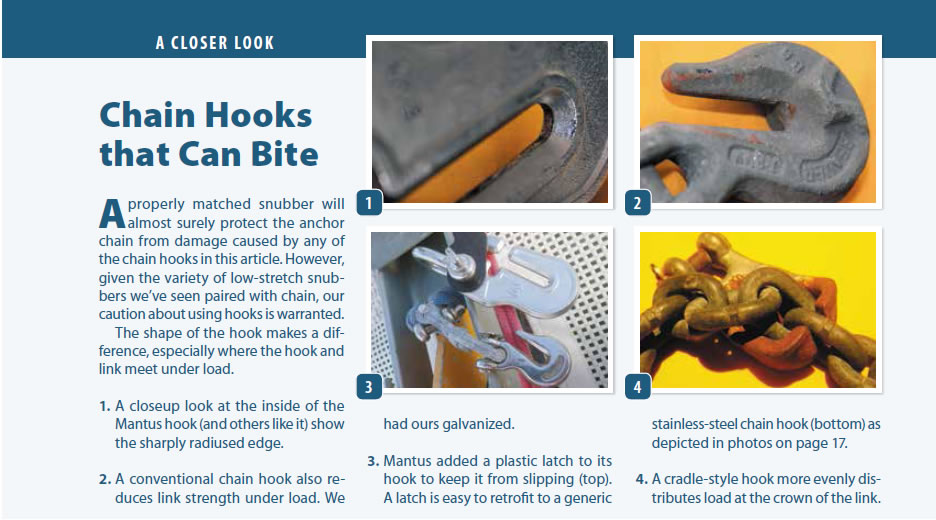

Industrial lifting hooks are reliable but users need to know that they can significantly weaken the chain. Several popular hook designs result in a concentrated point load where the edges of the hook come into contact with the chain. In our tests, the chain link where the hook attached failed at loads far below its rated breaking strength.

Chain hooks are made to fit a specific size of chain, so you need to buy the right size hook for your chain. A hook that is slightly too big or too small might work, but a bigger hook will slip off more easily and a smaller one can be more difficult to attach. The tolerances are broad enough that metric hooks will fit the nearest U.S. standard chain size and vice versa.

Photos by Jonathan Neeves

A disadvantage of most chain hooks is that you need to attach them to rode that has already cleared the bow roller and is well outboard of the pulpit. The ideal hook can be attached with one hand, so that the other is free to hold on to the boat. All of the one-handed hooks weve tried fall off almost as easily as they are attached. Hooks with latches are almost 100-percent secure, but you need two hands to attach and disengage them.

PS has tried a number of hooks that are easy to use, but not all offer a secure connection. Some designs are clearly stronger and better suited to the task of anchoring than others. Prices for a medium-sized chain hook range from $10 to $40.

Popular Chain Hooks

Wichard, a manufacturer with a long reputation for making high-quality stainless-steel marine hardware, has a neat stainless-steel, slotted chain hook with a spring-loaded retaining pin. Its well made, but installation and retrieval is two-handed. The spring-loaded clevis pin is very small, and even with a lanyard attached to the pin, engaging or disengaging the hook requires dexterity. You need to pull the lanyard to unlock the pin and simultaneously ease the hook.

Weve heard a few reports of the spring-loaded pin bending. If it bends while the hook is in use, the hook becomes even more difficult to disengage. We also have heard one report of a Wichard hook deforming under load, but we saw no evidence of weakness during our testing. It did not bend when others did-though it is much thinner. We like the Wichard hook, although it is much more expensive than other hooks and wed prefer it to be easier to attach.

The Mantus Anchors chain hook is one of the larger hooks we looked at (for the corresponding size of chain). We last reviewed it when Mantus introduced its injection-molded lock (see PS January 2015 online). Clever details include the two-way slot to reduce the chance for the chain to fall out, the matching shackle, and the one-handed plastic lock.

The plastic lock can break, but replacements are available. (You can also fabricate your own or use a substitute.) The more pressing concern, addressed in the accompanying article, is what happens to the hook under extreme loads. The hooks working surface, the load-bearing surface, has relatively sharp edges that concentrate the load on a small area of a chain link. Based on our testing, we cannot recommend any hook with relatively sharp-radius edges that point-load working surfaces.

Suncor Stainless makes a stainless hook with a slot like that of the Mantus hook and also has a tight-radius working surface that will induce point-loading. It lacks any way to lock the chain in place, but this appears to be an easy modification. As with the Mantus hook, we have concerns with this hooks tendency to point-load on the link.

The Peerless Industrial Groups hook we tested is an extremely common design offered in either steel or stainless under a variety of name and no-name brands. (Seafit is one marine supplier.) These elongated, fish-hook-style hooks come in two basic designs, each offering a slightly different way to attach the snubber-with a simple eye or with a jaw and clevis pin. A jaw and clevis pin can make it easier to attach and detach a spliced eye and thimble at the end of the snubber. (An anchor bend or stitched splice will also work instead of a spliced eye.) But adding a shackle to an eye-type hook accomplishes the same thing. The jaw-and-clevis type also makes it easier to make your own hook latch, as described below. Because there are so many sources for this type of hook, the trick is distinguishing which hooks are rated for high loads.

The steel version from the lifting industry is tested and rated for use with the G3, G43, or G7 chain commonly used for anchoring, but it is often not galvanized. Chain hooks specify a rated working load limit (WLL), but what that means is not clear. Does exceeding the WLL mean it will deform, or break? What percentage of the ultimate tensile strength (breaking strength) is WLL? Chain makers often publish the ultimate tensile strength, and the safety factor used to derive the safe working load. We expect the same for hooks.

The elongated, fish-hook-style hooks are easy to attach to the chain, but they also slip off fairly easily. PS contributor Jonathan Neeves made his own chain hook lock by simply attaching a thin piece of stainless plate. (This only works with the clevis-pin design as the clevis secures the plate.) The stainless-steel plate locks the hook onto the chain, but it makes attaching the hook a two-handed process.

A more pressing concern is the fish-hook-style chain hooks effect on chain strength. All of the generic fish-hook-style chain hooks can reduce chain strength by up to 25-percent under extreme loads, such as those that might be induced when using a short, inelastic snubber. If you are using a new, branded, 5/16-inch G30 or BBB chain (WLL of 1,900 pounds, with a 4:1 safety factor), chain strength is reduced to 1,425 pounds. If the chain is old or corroded, the safe working load will be even less. This illustrates why the snubber must be long enough to significantly reduce the peak loads. (See the snubber article in this issue for more on snubber lengths.)

Not all chain hooks reduce the chains working load limit. Chain hooks that are designed so that the chain retains full strength are sometimes called cradles, grab hooks, or hooks with wings or a saddle. You can find them with either an eye or clevis pin at the end that attaches to the snubber. There are other hooks sold by the major lifting companies (Rud, Pewag, and others; see the accompanying Contacts box) that don’t reduce the chains working load. Unfortunately, these are difficult to differentiate, except by price, from look-a-likes that actually degrade strength.

The load-bearing surface of a cradle hook is designed to evenly support the link, so that any load is taken only by the crown of the link. These cradle hooks are available from most lifting supply companies at G70, G80, or G100 strength. They are seldom galvanized, but this is something the boat owner can do using the Armorgalv process (see PS March 2015 online), but hot-dipped galvanized would be equally adequate. Some examples: Peerless 3/8-inch Clevis Cradle Grab Hook is coded part no. 8528480; Crosbys is designated A-1338; the Columbus McKinnon Clevlok Cradle Grab Hook and Van Beest Excel Grab Hook are also load tested (Grade 8).

There are many other manufacturers with the same cradle design, with a saddle-like, load-bearing surface to support the link. Load-tested G70 hooks of this design, used in the transport industry, are relatively inexpensive. These chain grabbers can become detached from the chain in some circumstances, but it would not be difficult to retrofit a latch.

Another chain-hook design can be described as a claw. The claw hooks are effective at spreading loads because they support the whole crown of the chain link. They are easy to attach one-handed, making them almost ideal for use with a snubber. The problem is that they fall off more readily than any other hook type we looked at. We have not been able to devise an effective retrofit to make them more secure. (Perhaps PS readers have an idea? Email [email protected] with details.)

We have tried using a claw chain hook and found it easy to attach and detach. Both Osculati and Ultra make chain-grabbing hooks that are derived from the claw, but neither offers a means of 100-percent security when attached to the chain. We like the concept of the claw, particularly the ability to focus the load on the crown of the chain, but because they tend to become detached, we are not big fans.

The last type of chain hook we looked at was a product from Kong called a chain gripper. The Kong chain gripper hook is effectively a re-designed shackle. Like a shackle, it is secure, and it loads the chain evenly, but it needs two hands to attach and retrieve. We have not yet tested this hook.

Conclusion

We think any device promoted for attaching a snubber to an anchor chain should not detract from the strength of the anchor rode or easily become detached. The likelihood of a chain-hook leading to chain failure in marine applications is unknown, but our tests and the lifting industrys strongly worded cautions regarding this are enough reason to be wary. This does not rule out the use of chain hooks for anchoring, just be forewarned. If you prefer to use a chain hook, use one that neither point loads the chain link nor has a tendency to fall off, and be aware of the compromises using one entails.

Some proponents of chain hooks will contend that we are over-emphasizing the hooks tendencies to fall off and that, so long as you keep a load on the chain, it will stay in place. But a constant load is no guarantee during a wild ride in an exposed anchorage. Gusty winds and short, steep chop can bring dynamic loads that are capable of dislodging all but the best-secured hooks.

For this reason, a gripping hitch remains our first choice for attaching a snubber to chain; our previous report shows how to tie several. We remain ambivalent of soft shackles; some of our contributors swear by them, others see them as more complex than necessary, given the security of a simple hitch. Except for the risk of abrasion (unlikely to occur during a single storm event), there is nothing inherently unsafe about using a soft shackle. We simply see no major benefit over an old-fashioned, tried-and-true hitch.

Common chain hooks are simple but insecure without a latch and potentially damaging to the chain if used on a short snubber. If you use a long snubber, it is highly unlikely that point loads from any of these common chain hooks will cause the chain to break, but if the same link is used time and time again, or over a long period, the cyclical loads could accumulate and possibly weaken that link. A saddle or cradle-style chain hook with some form of latch would be a better solution, since the load is more evenly distributed.

If you already use a chain hook, be conscious of its effect on rode strength and examine the hooks load-bearing surfaces. If there are sharp edges resulting in point loads, try to smooth the edges with a file, or discard the hook and buy a cradle style.