The phrase ‘cruising canvas’ has always had a sail inventory connotation, but today it’s even more descriptive of cockpit coverings that range from small spray hoods to full cockpit enclosures.

There’s good reason to go sailing under cover. Spray protection and shielding from the sun’s harmful rays lead the list. And it’s no surprise that cruising sailors have created a booming aftermarket industry that keeps canvas lofts and stainless tube fabricators busy. The usual routine involves a canvas loft manager and a boat owner collaborating on what the boat’s designer and builder failed to address.

The results vary. When all goes well, the tubular arches and fabric structure complement the lines of the vessel, provide welcome shelter, and still preserve the ability of a crew to handle sails and move in and out of the cockpit safely. In some cases, there’s too much of a good thing, and what emerges is a Conestoga wagon-like countenance that adds way too much windage and excessive vulnerability in a seaway.

Today, more and more sailboat designers have stepped up and added dodger and Bimini plans to their original drawings. Builders are providing molded mounting points on the deck for supporting hardware that shape their dodgers and Biminis.

In this review of cruising canvas alternatives, we will focus on factors that influence design and construction as well as look into materials best suited for soft and rigid dodgers, Biminis, spray cloths and other enclosures. From the start, we recognize that one size or design won’t fit all needs. That’s why it’s so important for the skipper to communicate to the loft designer or manager what their sailing priorities are and the range of conditions that they will likely encounter.

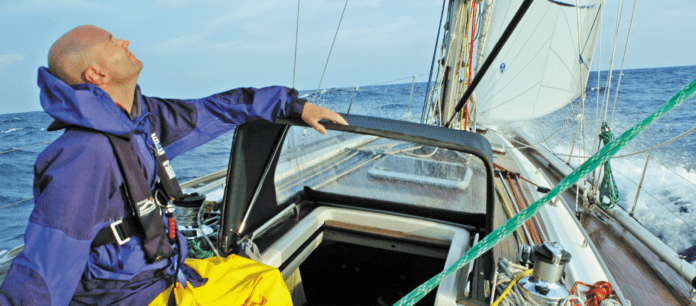

It’s interesting to note that the less-is-more cadre of performance-oriented sailors balk at cluttering up the cockpit with canvas that adds drag and provides no lift. They cringe at the thought of obstructing the full view of the sail plan. Those racing to Bermuda or Hawaii for example, tend to do so with minimal cockpit covering. Even so, many participants sail these races with a small, collapsible dodger that allows the companionway hatch to remain open—even when the spray is flying. When the crew is perched on the rail or working in the cockpit, they rely on hats, sun shirts, gators, glasses, and sunblock along with a good set of foul weather gear. But as this full-speed-ahead ethos devolves into the pleasure of cruising, sail area decreases and dodger and Bimini square footage increases.

At present, the independent dodger and Bimini duo is a very sensible combination regardless of whether you sail a center- or aft-cockpit vessel.

SAFETY CONCERNS

Unfortunately, what often goes unnoticed are the safety concerns that arise at sea. These are often linked to an excessive canvas coverup. So, when finalizing design plans, ask yourself, how watch keeping, and the helmsperson’s visibility will be affected by the proposed structure. Thanks to the ability to use clear plastic windows (vinyl, acrylic or polycarbonate), a 360-degree view can usually be maintained. It’s also important to make sure that the shortest and tallest crew members have minimal obstructions to their sightlines.

Equally as important from a safety vantage point, is the maintenance of an unencumbered pathway to and from the helm and in and out of the cockpit. All too often, larger canvas covers work just fine in calm weather, flat sea conditions and when anchored, moored, or snugged up in a slip. However, it can be a completely different story in a seaway when an awkward contortion is needed to get in and out of the cockpit.

Don’t trade big tent ambiance for a detour along the lifelines and an elevated risk of falling overboard. In heavy weather, reefing is usually quite straight forward, but removing or folding up a large Bimini or even larger, more elaborate, full cockpit enclosure, can redline the risk meter.

Latitude and weather patterns play a big role in selection of cockpit coverings. The higher the latitude and cooler the climate, the less desire there is for shade. It’s no surprise to see a lack of Florida rooms in Norwegian fjords. But in the often rainy and overcast wonderful cruising ground in the Pacific Northwest a cockpit enclosure often mimics a trawler’s pilot house. The more sun and the lower the latitude the greater the lust for shade. And in cooler, cloudy higher latitudes, lifeline supported weather cloths can add much appreciated spray protection. However, veteran cruisers rig these spray protectors with weak, low tensile strength line, lashing the lower portion of the canvas weather cloths so that a breaking sea will not collapse lifeline stanchions. Water weighs over 8 pounds per gallon, and when hundreds or thousands of gallons of accelerated wave face contacts a large, relatively weakly supported surface area, bad things happen. In such situations, an abrupt energy transfer results in a near instantaneous collapse of the underlying structure. The larger the canvas covering, the more vulnerable it is to impacts from wind and sea.

DODGERS

The venerable companionway dodger is still a cruising sailor’s best friend. Its strategic role includes allowing the main hatch to remain open, even when rain is pouring down and you’re beating to windward in a blow. Its stainless steel, bow-like, arched framework and secure mounts allow it to be folded forward or pivoted up into position. When combined with a spray hood—a garage-like shelter that the main hatch slides into, a dodger can keep the companionway ladder and accommodations below quite dry, even when the spray is flying.

The traditional companionway dodger evolved and expanded into a cockpit dodger spanning the full width of the aft end of the cabin house. It turns the forward portion of the cockpit into a highly valued roost and is a good spot to sit and maintain a watch while the auto pilot or self-steering vane handles the helm. It’s attached forward, at deck level to the spray hood over the companion way hatch and to a molded deck flange specifically intended for dodger installation. The mounting hardware includes twist-fasteners and snaps that connect the canvas to the FRP surface. These fittings have proven to be quite reliable, but when poorly installed they can be the cause of severe core damage, especially in areas where Balsa wood has been used in the sandwich construction. The problem stems from drilling a hole through the outer FRP skin and not properly closing off the penetration or bedding the screw threads themselves. Over time, the fitting allows water to enter the Balsa wood and rot soon follows. Left unattended, the problem worsens, and large areas of core material can be destroyed. Newer boats are built with specific dodger mount coamings negating the need to drill holes into the cabin house itself.

In addition to expanding the dodger footprint, as time went on, zippered windows were improved, leathered handholds appeared on the trailing edge and stainless-steel grab rails made transitioning from the cockpit to the side deck safer and easier. Even so, it became clear that what works splendidly on one sailboat often fails on another. Awareness that one size or one dodger design doesn’t fit all is a major consideration. Take for example the issue of winch position, sheet leads and access in and out of the cockpit. A larger, longer dodger may hold appeal because of the shelter it provides, but if it forces those transitioning to the side decks to hobble over sheets and winches, the former advantage may be nullified by the latter’s safety implications.

In many cases the coach roof’s handrail, meant to be used by those leaving or entering the cockpit is rendered out of reach by a wide dodger. The net result is for those heading out of the cockpit to reach outboard and use the lifeline as a handhold. Modern sailboats are quite beamy aft and without a reliable handhold, getting around the dodger while entering or leaving the cockpit can be quite challenging especially in rough seas. Adding a sturdy stainless-steel tubular handrail to each side of a dodger is a big plus and worth the extra expense.

The hard dodger is hard to beat, especially when it comes to protection from the elements and the right place to stand a night watch. The best hard dodgers aren’t add-ons but were conceived by the boat’s designer. They remain structurally separated from the main accommodation and don’t eliminate traditional sliding boards and a companionway hatch or watertight door that isolates the accommodations below. There’s enough room to tuck into a cushioned seat and stay dry. And aboard larger sailboats there’s even room to stretch out. Electronic displays can be nestled under the enclosure, with a clear 360-degree field of view and you are more that half way to a pilot house but still have quick access to all the lines and sheets.

BIMINI TOPS

A Bimini is a salty term for an underway awning that usually covers more of the cockpit than a dodger. It’s a horizontal shelter that blocks sunlight and showers but lets the breeze flow through nicely. With a surface area that ranges from moderate to massive, it may be challenging to support biminis adequately. Flimsy framing may not be initially noticed but once you have weathered a significant cold front passage or a vigorous summer line squall, all of the shortfalls in support will makes themselves known. In such cases a poorly supported Bimini starts shaking like a Labrador Retriever just out of the water. The good news is that most Biminis fold up like the top of a 1969 Mustang convertible, and you can tuck things up before that front or thunderstorm threatens to unstep the support structure or shred the canvas.

Bimini design is a challenge that engages a familiar refrain of crew comfort versus dynamics of sailing. On one hand, the lower the latitude, the more appreciated shade becomes. But sailing under cover can hamper sail trim and even raise more safety concerns because of the obstacle path presented by the support stanchions ands extra bows. Once again cockpit entry and exit is important, as is day or night usability along with design features that work in calm or chaotic seas. Is there room to drag along a sail bag that resides in an aft locker? Quite often, the biggest design challenge rests with determining the appropriate spacing between the end of the dodger and the leading edge of the Bimini. Sunlight abatement calls for a minimal gap while a sailor’s need for safe, near instantaneous sprints forward and aft demands a good-sized slot and clear access to the inboard side deck.

When it comes to Biminis, sunlight blocking is a big deal. Many sailors assume that white is a cooler color, reflects light and doesn’t heat up as much as other colors. That’s true in some cases, especially when a white vinyl top layer is bonded to a dark conventional cloth underlayer. The first dodger installed aboard my sloop Wind Shadow was just such material and it reflected sunlight and was much more opaque that Sunbrella and WeatherMax. Unfortunately, the lower layer was a mold magnet in the tropics and the use of a dilute Clorox spray soon rotted the bottom layer that provided structural support to the vinyl top layer. Since then, I’ve been happy with dark blue Sunbrella and WeatherMax.

When it comes to dodgers and Biminis, a key goal is minimizing the translucency of the fabric, and color plays a key role. The main reason why white is not the best choice in the material mentioned above is that much light penetrates the material and infrared long wave radiation bounces back and forth between the deck and the underside of the awning. This mini-greenhouse effect raises the temperature, and darker colors may get hotter on the surface but those underneath the cover will be cooler.

ENCLOSURES

There’s been considerable growth in popularity of canvas cockpit enclosures (which some are starting to call the “Florida Room”). They encompass even more canvas square footage than the dodger/Bimini combo, and usually include drape like side curtains extending down to the rail. On the upside, it maximizes under cover living space and increases shelter for those living aboard in inclement, cooler environments. Preferably, the side curtains can be unzipped, rolled up or otherwise removed, leaving what amounts to a large awning providing sunshade yet open to breezes from all directions.

The fully covered cockpit concept has grown popular with those navigating the ICW in Fall and wintering in Georgia or Florida. The ability to make this inside passage sheltered from ocean swells eliminates the worry about being caught in rough seas and breaking waves. If you’re living aboard, the big plus is like adding a second story to your house. In rainy, colder climates, the mud room is now in the cockpit rather than down below in the cabin itself. For cruising sailors who plan to harbor hop, gunkhole, or cruise in protected waters during fair-weather sailing seasons, turning the cockpit into a “Florida Room” makes sense.

The downside of this big tent approach to cockpit covering includes excess windage, diminished view of sails and in many cases, a dangerous pathway transition when heading into or out of the cockpit. However, those making a run to the Caribbean in the late Fall, face a very different challenge and must cross the fickle Gulf Stream at a very volatile time of year. In rough conditions, the best place for a big Bimini or a collapsible Florida Room is stowed below in the forepeak or aft locker. Reefing sails in a Gulf Stream squall is tough enough but coping with wind and sea along with excess cockpit canvas can become a major challenge.

It’s clear that sailing in a big tent has its ups and downs. But there are some caveats. Number one is what happens offshore when you encounter a run-of-the-mill gale with 35-40 knot winds and 15-to-20-foot breaking seas? The teepee like structure in the cockpit may survive the wind, but water is 400 times more dense than air and a swimming pool’s volume of sea water dropping onto the tube and fabric enclosure won’t go unnoticed.

The added windage also affects sailing performance and is likely to introduce steering characteristics that won’t appeal to the helmsperson or the autopilot. Lastly, a good definition of “ordeal” is trying to reef the Florida Room at sea as conditions go from bad to worse. So, in your look at cover options, one of the questions to ask is, will the screened in porch-like cockpit be as cherished at sea as it is at anchor? And can it handle gale or storm force conditions?

1. Wide cockpit, modern designs vastly increase Bimini and dodger surface area. Multiple support bows are needed. Windows in the overhead must provide good visibility for sail setting, reefing, and trimming on all points of sail.

2. In warmer more friendly latitudes, sun rather than breaking waves is the culprit. A Bimini with a two layer vinyl (white) and polyester (blue) fabric reflects light. Mold resistance also is improved.

3. Windows in Biminis are a must if sail trim and setting is a priority. Closing up the flap when not on board can prevent puddled rain water from acting as a lens, refracting light and causing damage to sailing instruments.

4. Many new cruising boats add fiberglass structures that support dodger canvas. With an autopilot remote control inside the dodger, watch standers have both weather protection, helm control and full visibility

5. A good dodger allows for winch work, provides shelter and allows a crew to pop out and have easy access to sheets, guys and especially the helm. Keep glazing clear (see “Long Term Clear Vinyl Protection,” PS November 2018).

6. Spray cloths, a big Bimini and side curtains plus an array of safety gear can become the targets of a breaking sea. It’s important to rig covers and safety gear in keeping with the cruising conditions.

This piece was originally published October 14, 2022.

Biminis forever! I sail in the shade.

We have a dodger and a hard top bimini, with a removable (zipper) cover that connects between the two. We never sail with the cover in place. It comes off when we set sail and doesn’t get reattached until we’re docked/moored/anchored. It’s virtually impossible to see clearly with it attached. We’d spend a lot less time hanging out in the cockpit on sultry days without that cover though.