Tempis fugit . . . times a-waistin’ . . . fast flies the irreparable hour . . . However you choose to use your scarce time, we’ll wager that you’d rather not spend it removing bottom paint. If you are an owner of an older boat with a decade of accumulated hard bottom paint that is flaking and cracking, now is a good time to start weighing your options for removing the old paint. Should you do it yourself, or hire the professionals—or a bit of both?

In past reports on removing bottom paint and barrier coats, we’ve explored various methods to do the job safely. But more recently, in the light of our depleting youthful vigor, a diminishing number of do-it-yourself boatyards, and the need for personal protection against fine particles and organic vapors, our enthusiasm for a do-it-yourself approach has steadily waned. Although the substantial cost involved in renewing a bottom can be daunting, keep in mind that money and labor invested now will make subsequent bottom jobs faster and cheaper, so there is a residual benefit. Provided you have access to a do-it-yourself yard, are serious about personal protection, and don’t overextend the periods between reapplying bottom paint, your next decade of antifouling jobs could be do-it-yourself jobs.

As I recover from my own five-week long do-it-yourself paint removal project, I am reminded of a report by Ralph Naranjo, a former boatyard manager, marine safety expert, and Practical Sailor editor-at-large. Ralph was one of the last Practical Sailor testers to undertake a comprehensive test of coating removal methods and products (see “A Smorgasboard of Tools Required for the DIY Epoxy Barrier Coat Removal”). An excerpt from that report appears below (“Is It Worth It?”), along with Ralph’s guide for estimating the amount of time required for any boat bottom project (“A Mathematical Decision-maker”). The DIY work calculator first appeared along with Ralph’s report on Soda blasting, “Soda Blasting 101.”

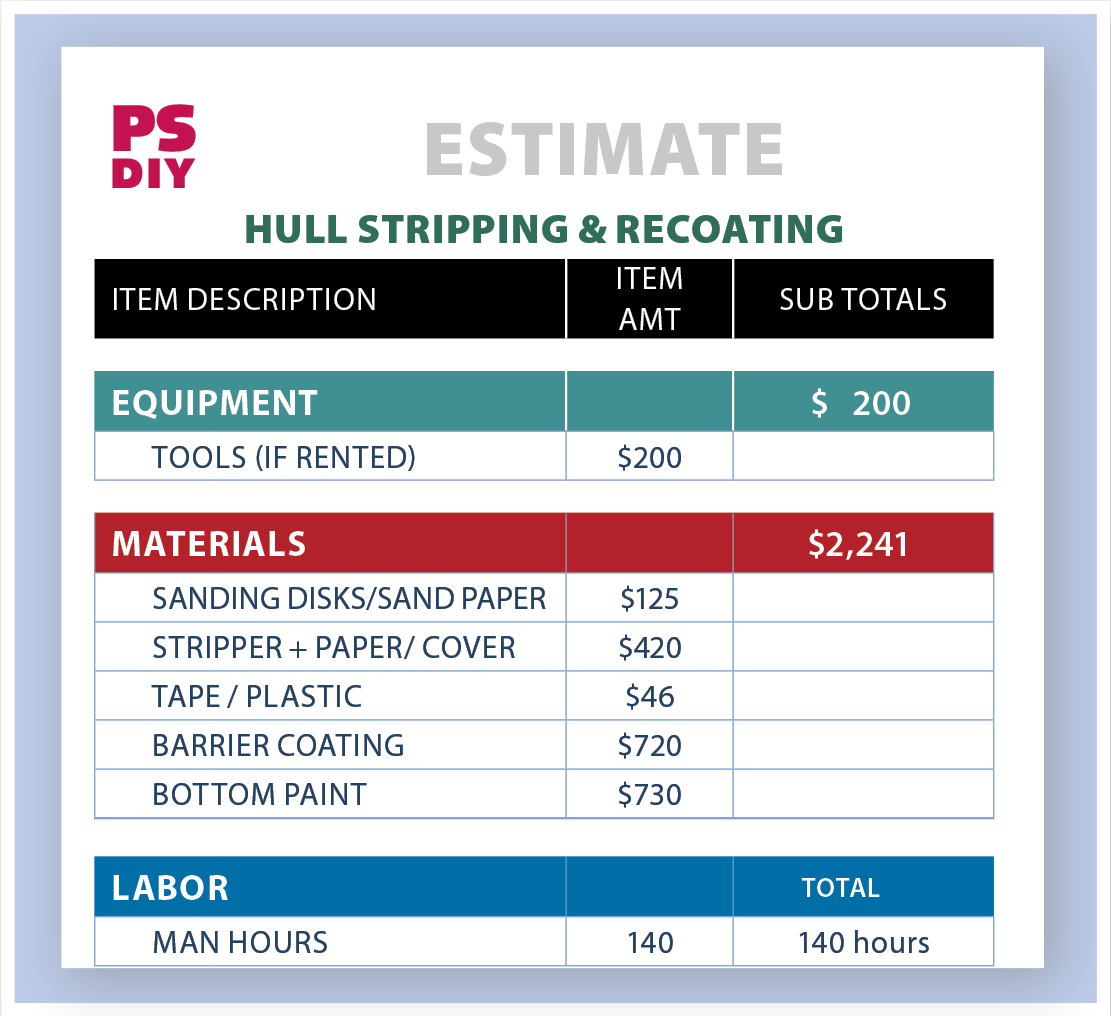

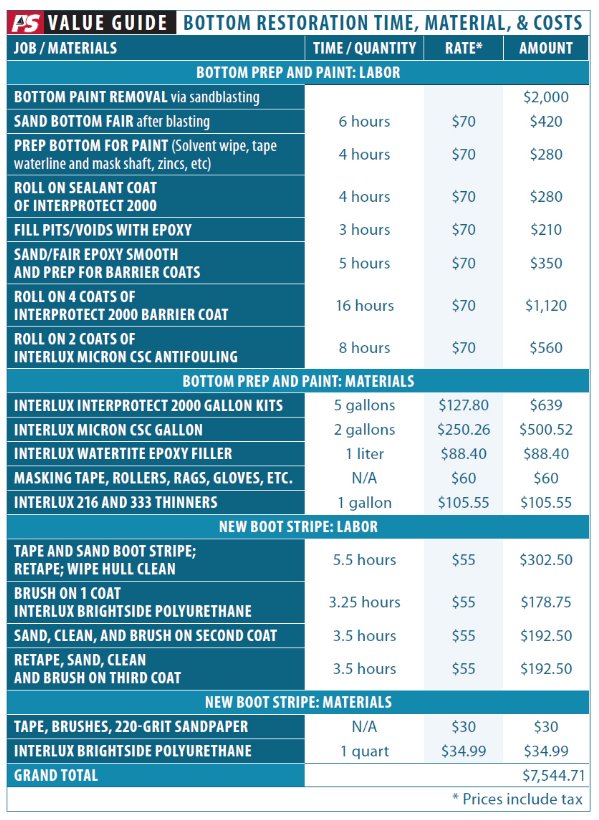

Not long after Ralph’s report, we went back into the boatyard and followed the bottom restoration of a Bristol 35.5 owned by the publisher. The Bristol, however, got the royal treatment, as the owner handed the project over to local professionals. The work and materials tallied in the table below are detailed in the report “Bottom Paint Makeover.”

If you are still in the water as you consider these options, we also have two helpful boatyard reports for those still choosing a yard “Do it Yourself Boatyards,” and “Do it For Me Boatyards.” Hopefully, you are already out sailing, and the next haulout is from your mind. But if you have decided to finally “bite the bullet,” as Ralph puts it, I hope these reports can help. If you have specific questions about removing, choosing, or applying bottom paint, or if you have a boatyard to recommend, you can email us at [email protected].

Is it Worth It?

At the conclusion of the paint removal ordeal (two full weeks), I asked myself, “Is this scale of commitment really what your typical DIYer should tackle?” The answer? An uncertain “maybe.”

The job certainly can be turned over to pros and is a prime candidate for media blasting, but many yards don’t want the airborne residue associated with the process. Tenting the boat or moving it into a building adds expense. And when all is said and done, the epoxy barrier coat is pretty immune to baking soda and may require blasting with a more aggressive grit that can tear into the gelcoat as well as remove the barrier coat. The slow and arduous combo of chemical stripping and sanding used to rid Wind Shadow of 26-year-old barrier coat left the gelcoat intact and provided an even surface over which to reapply the same epoxy system that had endured for over two decades.

Now that more and more barrier-coated boats are reaching the end of the paint’s lifespan, owners will be looking for answers about what to do next. If there is a significant amount of interlaminate blistering in addition to barrier-coat blistering, it may be time for a “peel.” This even more aggressive approach cuts all the way down to FRP laminate, removing barrier coat, gelcoat, and the pocked first layer of FRP laminate. Once the offending surface has been cleared away, the remedy is to re-laminate whatever schedule of material was removed. The new composite skin incorporates vinylester or epoxy resin, and the complete job includes re-fairing the surface, barrier coating, and finally bottom painting the underbody—a job that dwarfs the efforts bestowed on Wind Shadow, and one that will require professional intervention.

Those considering such a project as removing barrier coats should first evaluate their skill level, and then weigh the man-hours and cost of the project versus what it would cost to have a professional do it. In my case, removal options included subcontracting a soda blasting, which would cost $2,500 and would only rid the hull of antifouling paint, not the failed epoxy barrier coat. A heavy- grit media blasting to remove the epoxy—along with much of the gelcoat—was considered too aggressive for this project, although we did use it in a subsequent bottom job on another test boat.

Leaving the whole job to the pros would’ve been pretty costly: A “peel” or blast approach and the followup fairing, resurfacing, epoxy barrier coats, and bottom paint would run about $10,000-$15,000. Rates, of course can vary by region. We paid just under $8,000 to strip and refinish a Bristol 35.5 in Connecticut, and just under $5,000 to strip and refinish the bottom of a 30-foot Yankee 30 in Florida. Both were media blasted (soda-blasted in Connecticut, wet-abrasive blasted in Florida). In each of these two project, the paint and barrier coat removal accounted for $2,000 of the total cost.

Mathematical Decision Maker

So, how much work is it, really? An easy way to compute the do-it-yourself labor commitment involved is by timing how long it takes to scrape clean two 1-square-foot patches. The first is in the center of the least well-adhered paint; the second is in the midst of an intact portion of the bottom. Dry scrape each section with a thin-bladed putty knife and a sharp drag-type scraper, noting the time it takes to remove about 90 percent of the coating.

Next, estimate the percentage for the bottom that should be dubbed easy to scrape paint versus areas where the antifouling is stuck like glue. Finally, you need to roughly calculate the square footage of wetted surface area (WSA) that comprises the underbody. This is by no means an ordeal that requires advanced geometry. It’s a rudimentary calculation that requires only three bits of information (waterline length [Lwl], maximum waterline beam [Bwl] and draft [T]). The user-friendly formula (WSA = Lwl x (Bwl + T) applies to most heavy displacement cruising hulls. Multiply by 0.75 for medium-displacement vessels and 0.5 for light-displacement boats. This oversimplification of wetted surface calculation would provoke a scolding from David W. Taylor, William Froude, and other dons of naval architecture, but for a paint removal estimate, it works just fine.

Finally, take the results of the calculation and divvy it up according to the proportion of easy versus difficult regions of paint removal. For example, if only 15 percent of the bottom is cracked and peeling, and the removal time per square foot in this region is 30 seconds—as compared to four minutes per square foot in the well-adhered section—the ratio is by no means encouraging. Applying the ratio to the wetted surface calculation drives home the level of paint scraping required.

Let’s assume that the vessel has a 30-foot waterline, 6-foot draft, a waterline beam of 10 feet, and is a medium-displacement vessel. Our fuzzy math for a medium-displacement sailboat fills in the WSA equation as follows: WSA = 30 x (10 + 6) (.75), and the result is 360 square feet.

Next comes the all-important apportionment of easy versus difficult paint removal. In this case, 85 percent falls into the tough-going regime that equates to four minutes of toil per square foot (0.85 x 360 x 4 = 1,224 minutes of misery). Add in the easy scraping (0.15 x 360 x 0.5 = 27 minutes), and the result is 1,251 minutes, or just under 21 hours of serious scraping. This is unequivocal arm-in-action time, and the ride to the boatyard, coffee breaks, and chats with sistership owners, stops the clock.

This method to estimating work on the hull bottom could also be applied to a topside or deck project. Just be sure include some awkward work areas in your “sample” panels for estimating the total time required. Removing paint in some areas—cockpit corners, or near trim—can require two to three times more work than flat areas of the hull, and this needs to be taken into account.

Chemical paint removers, a large crew, or true friends can soften the blow, and so can a more deteriorated surface. If 70 percent of the bottom paint has a cornflake-like look, it will allow a thin bladed putty knife to effortlessly separate it from the hull skin, and a very different labor picture arises. Run the numbers, and you’ll find that in this scenario, 9.3 hours of toil would strip away the residue. In short, it’s not the bad spots you need to worry about, it’s where the paint looks good that causes all the problems. This is why procrastination rules, and we tend to postpone bottom paint removal in favor of spot prepping and feathering in the bad spots. At some point, it’s time to bite the bullet and tackle what’s been pushed down the road.

I did this job over two months late last year on my new-to-me Nor’West 33. I’ve sworn to leave boating before I ever do it again!

I had my 1982 Sea Sprite 34 “glass-blasted” several years ago. I was afraid that the glass would be too aggressive (no apparent blisters- just 30+ years of bottom paint flaking in a lot of places). The contractor was well-recommended (here in Maine), tented the boat from waterline down and under, operator in full air-supplied suit inside the tent, and did a fantastic job. In most all areas, the pre-existing barrier coat remained on the boat. The work was done on my property, so no boatyard rules to negotiate, but there was not a spec of residue left on site when the contractor was finished. I faired the very few gelcoat voids that were opened up by the blasting, as well as “battle scars”, then 4 coats of Interprotect, hard bottom paint over partially cured last coat of barrier, then two coats of ablative- 3 seasons later (with ablative renewals), no lifting or any other issues. Well-worth the expense!

In all situations where mechanically powered sanding is to be done, a high quality sander with very good dust collection is an investment within long term returns. But, it only works as well as the dust extractor–the vacuum attached. The options for the vacuum are either an expensive system with high dust collection efficiency and down to potential HEPA ratings with an upgraded HEPA filter. Or, the same performance is available with a shop vacuum and the addition disposable paper bag liners and an upgrade to the standard pleated filter to high-performance or HEPA-rated fllter, both at very reasonable costs.The noise and cfm perform are very comparable at a fraction of the cost of the aforementioned commercial dust extraction systems.