I had been driving my 34-foot catamaran down the Chesapeake Bay at 8-9 knots all morning, propelled by a fresh breeze. “Thud … thud.” The boat lurched slightly to port, telling me I had struck something substantial on that side. I hadn’t struck bottom—I was in 50 feet of water. I eased the sails and dashed below to check for water in the bilge and crash tanks (thankfully, none), and took a moment to absorb what had happened. The autopilot beeped an off-course alarm, common enough in gusty conditions, but when I disengaged the autopilot to make a manual correction … nothing. The wheel would not budge and the boat was turning very slowly to port…and the shoreline.

I was able to resume a true course by adjusting sail balance and adding a little drag to the leeward side by lowering a retractable outboard engine. I selected an alternative downwind destination, and when I was close enough, lowered the sails and played the twin engines against each other to maneuver the channel. After anchoring, I donned a drysuit and examined the bottom, thrilled to find only scuffed bottom paint and a rudder shaft that had been bent just enough so that the blade scraped the hull. Because it was a catamaran, I was able to disconnect the faulty rudder and finish the cruise using the other with no affect other than mushy steering. Without twin rudders, the options were repair in a distant yard or a long tow home. Without twin engines I could not have entered any harbor and would have either anchored off a lee shore, gotten a tow in, or ended up on the beach. I’m going to show you how you can rig an emergency steering set-up in 10 minutes using only stuff you have on board. Really.

A STITCH IN TIME

Loss of steering is one of the most common reasons for offshore abandonment; an otherwise sound boat that can only go in circles is not much use. Loss of steering inshore is less dangerous, but striking submerged logs or an uncharted piling are far more likely. In “Sailing Without a Rudder,” June 2017, we tested and reviewed emergency steering with commercial drogues, including the Delta Drogue, Gale Rider, Sea Brake, and Small Shark, and a JSD segment (the last did not work well).

Our findings back then: “A drogue will only allow for downwind courses, perhaps a broad reach at best.” In fact, properly rigged, we were able to sail slightly to windward in good conditions, with the true wind just aft of the beam in near-gale conditions, and any course we wanted using the engine. Although we probably wouldn’t try to motor right into our slip, straightforward channels and most harbors presented little difficulty, and certainly we can get within warping or dinghy tow range.

The principle of drogue steering is the same as steering a canoe by dragging a paddle. To turn right, you drag the paddle on the right side, just enough to turn the boat without slowing it too much. The closer the paddle is to the natural pivot point of the boat and the farther outboard, the quicker the turn.

DROGUE CONCEPTS

Commercial drogues are easy to rig because of their light weight. They are stable in strong conditions and are well proven during ocean crossings. An 18-in. diameter works for 30-ft. boats, a 24-in. diameter drogue for 35- to 40-ft. boats and so forth, following manufacture recommendations. The Gale Rider is more like a net—go up one size for equal braking and turning. They store in a compact bag. You will need a 10- to 20-ft. length of chain to hold them in the water. Go up a size if you also intend to use the drogue for storm management. (See “How Much Drag is a Drogue,” September 2016 for reviews, sizing, and more rigging and use details.)

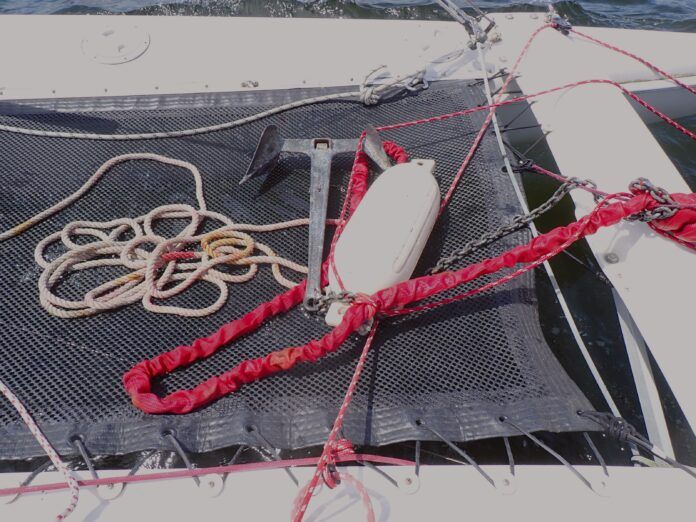

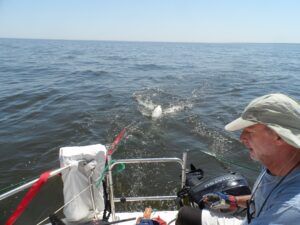

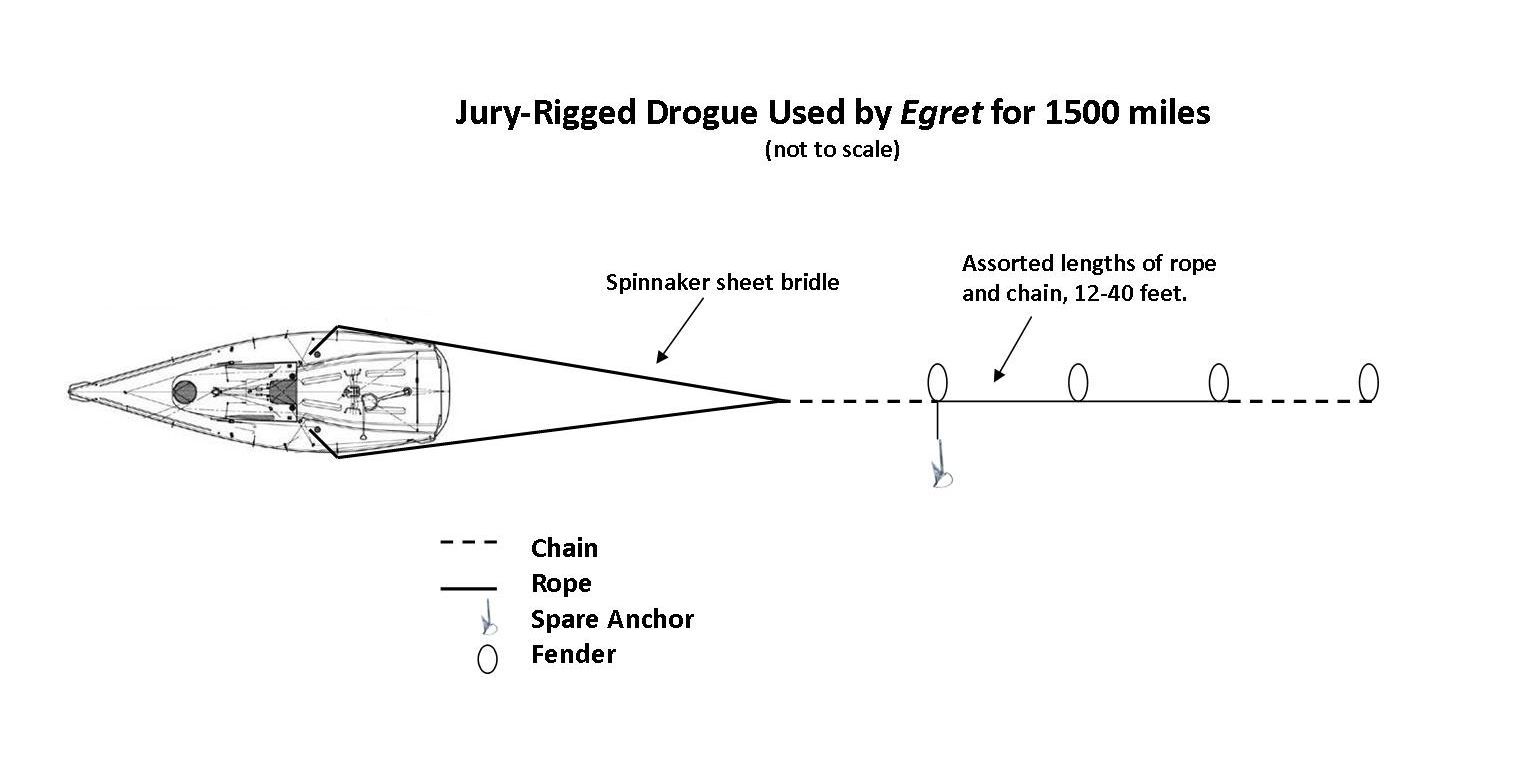

The Jury Rig Drogue. The costal sailor can jury rig an effective steering drogue by hanging a standard- sized anchor (but not a Danforth/Fortress type—they skim the surface more than drag) just below a fender large enough to float it. I’ve tested this rig as well, and through more awkward to lug around, once deployed it works just about the same as a commercial drogue. If you need more braking for good control, add a second anchor below a second fender, 20 feet farther back, and so forth. After their rudder snapped off in 2011, Patrick and Amanda Marshall used this sort of rig for 1500 miles across the Atlantic Ocean aboard their 39-ft. Sweden Yachts Egret.

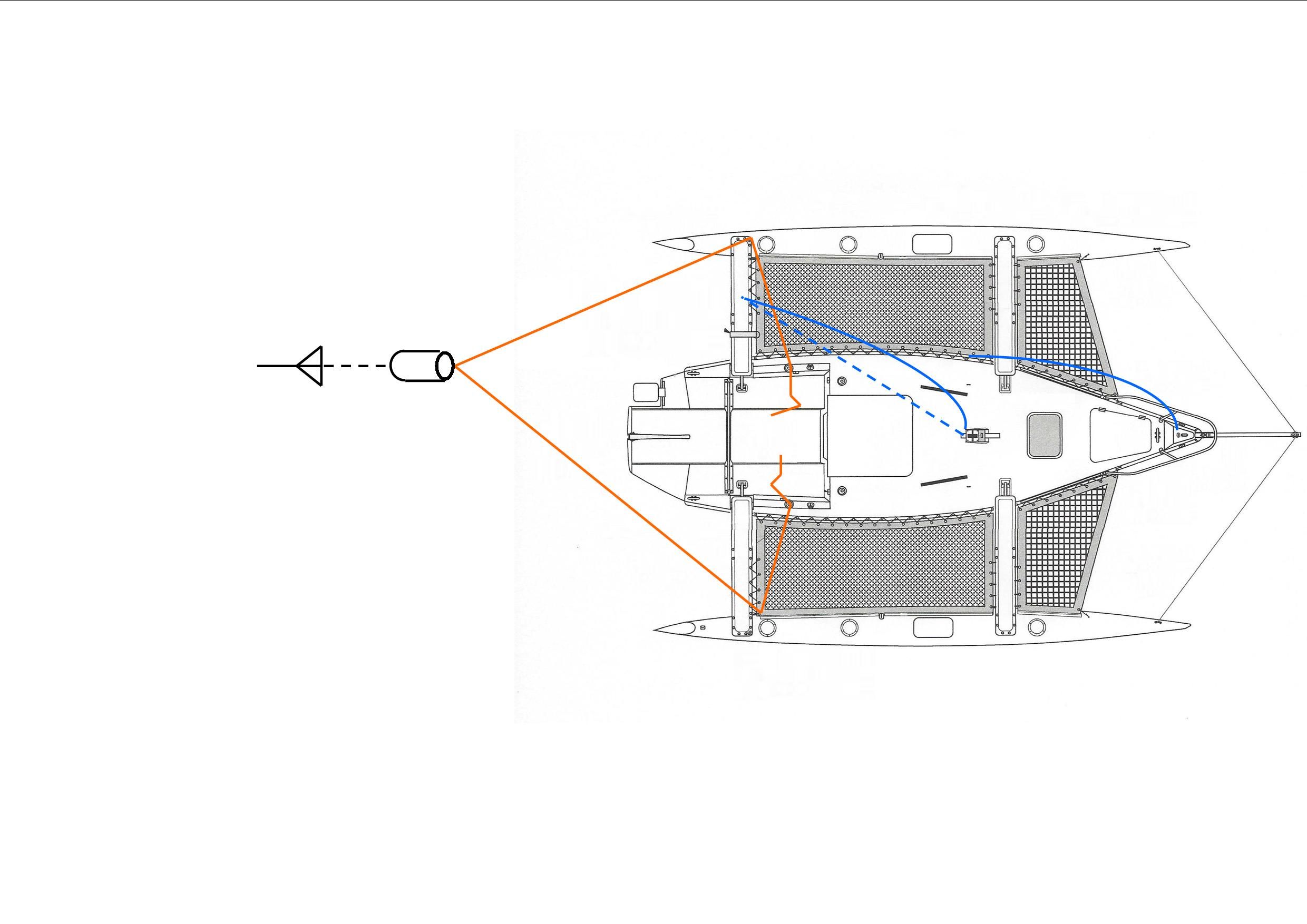

In Egret’s jury-rig drogue arrangement depicted below, control lines were led to blocks just aft of the beam, then up to primary winches. This forms a bridle that is connected to a length of chain and rope, supported by fenders. A main anchor (not a Danforth or Fortress, as they tend to skip) settles the arrangement into the water where it can furnish needed drag.

“What about a bucket?” We strongly recommend against it. The cylindrical shape makes for unstable towing, whereas the inverted conical shapes of commercial drogues are designed for stability, and even the irregular shape of an anchor tends to be stable. The drag force on a bucket will range from 90-150 pounds at 5 knots, and you will rip the handle off in the faster surges. The drag will only be enough for boats up to about 25 feet and not for storm conditions. The anchor/fender system is stronger and more stable.

Drogue Rigging. For maximum maneuverability, attach the bridle control lines outboard of the pivot point and at the widest part of the boat. For monohulls, this is generally a short distance aft of the mast and near the center of the keel. However, such a radically forward location is something of a compromise; with lines attached this far forward, the bridle can easily wander under the boat—not a problem if the rudder is gone or if speed is steady—but it is a significant fouling risk if pieces of the rudder are still there, the seas are lumpy, and sailing progress is irregular. The best compromise for monohulls is about 65-80% of the way aft. That will give you enough beam for leverage, but with less risk of the bridle tangling under the boat. Multihulls should place turning blocks near the transoms; the leverage is sufficient and the bridle will stay out from under the boat. Move the turning blocks forward to the keel location only for monohulls, and only when you need fine control, for example, when motoring into harbor. Setting up a drogue bridle is a bit easier on a multihull, below. The bridle will be wide enough to effect steerage if you mount it to the outboard side of each ama.

Deploying. I like to use the spinnaker sheets. They are pre-rigged, the turning blocks are in a suitable location, the line size is good, and they have a fair and familiar lead to the winches. Equalize the length of the sheets and set them at 1½ boat lengths; it is easier to start off with a relaxed downwind course and the drogue a little too far back than to risk sudden turns and tangling lines under the boat while getting things tuned in. Don’t shorten the bridle for better speed or set a higher course until the boat is making steady progress. Never underestimate the risk of getting a line under the boat when starting from an awkward, rolling, drifting position. I’ve done this several times. So long as there are no knots at the end of the lines, you can generally just let one side go—make sure there is a stopper knot— recover the drogue, and start over. If things aren’t going well, consider reefing or dropping the mainsail.

In light to moderate winds, the drogue should be pulled in as close to the transom as practical; steering inputs are more immediate and the drogue is lifted up near the surface, reducing drag, and improving speed and pointing. As the wind increases, ease the drogue farther back from the boat, to increase drag (steering force) and to keep the drogue stable (they like to surface and skip around in steep waves, similar to how a ground anchor won’t set at short scope).

Reefing. Reduce sail when boat speed exceeds 5.5 knots, starting with the mainsail. Keep the traveler lower than normal on all courses, since the rudder is no longer contributing to lateral plane. As soon as the true wind moves aft of the beam, strike the main.

Strength and Materials. Spinnaker sheets are both long enough and strong enough for emergency steering. The sizing below is a rough guide based on gale conditions and normal steering drogue size recommendations.

As the wind strengthens, pointing ability rapidly decreases. Some of this is a consequence of the increased drag, but mostly, it is very difficult to stay in the groove with waves. By 20 knots, I gave up on windward courses. Running the engine at low RPMs dramatically improves directional stability both reaching and to windward.

Steering Under Power. All of the drogues were able to provide controllable steering on flat water and moderate waves through a range of wind speeds. In winds and waves over 20 knots yawing becomes considerable and a course 20-30 degrees to one side of the waves is more practical.

Recovery. Again, never underestimate the risk of getting a line under the boat. While it is possible to ease the work of hauling in the drogue by backing the boat under power, the risk of fouling the prop or rudder is considerable; if hauling is interrupted for any reason, it is easy for the boat to coast back over the rode and drogue, and the prop suction will do the rest. At most, very low revs should be used to slow the boat, leaving some tension on the rode while the majority of the line is hauled in, and then put the engine in neutral while the last 20 feet are brought aboard. If the waves are steep and the wind is dying, the load is generally very light on the back slope of each wave, and 5-10 ft. can quickly be hauled in with passage of each wave. Put two turns on the winch, lock the rode down as the tension comes back on, and patiently wait for the next lull or back slope. Don’t let the line get under your feet or around a wrist; there can be a lot of surging and the loads can be dangerous even in light winds.

CONCLUSIONS

Until I struck that log and felt the helplessness of sailing in circles, I believed that drogues were for ocean crossings. How stupid to become utterly helpless because one bit of metal is bent just 2 degrees. However, it was encouraging to see just how well a drogue can steer, even one made from an anchor and a fender. Practice on a nice day and then on a not-so-nice day. There are always a few boat-specific wrinkles to be ironed out.