A deep, ballasted keel does a lot of good things. It lowers the center of gravity, provides lift to windward, and stabilizes the boat. It can add great strength if integrated into the construction of the hull, allowing the boat to sniff soft bottoms without damage.

There are downsides. Trailering is impractical. Countless shallow creeks and snug harbors become inaccessible. Docking is more expensive.

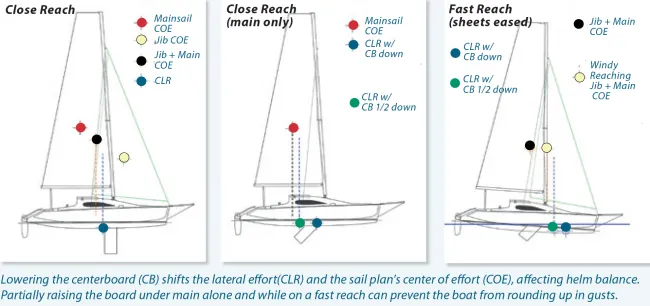

A centerboard is one solution, but there are differences. You probably read something about raising and lowering the centerboard or daggerboard in a book on dinghy sailing years ago, and unless you’ve been racing centerboard boats all these years, you’ve probably forgotten the details. Here’s a little refresher.

Even for the cruising sailor, centerboard position is as vital an adjustment, as sail balance and trim.

Balance. On a poorly trimmed boat, one of the largest sources of drag is often excessive rudder angle. Assuming you have the typical rudder profile (NACA 0021), the optimal helm range is generally 2-4 degrees when close hauled. A few degrees helps it share the work of the keel, providing lift to windward. More rudder angle and you are increasing drag, and if the angle exceeds 6 degrees, you are courting a stall when a strong turn to leeward is needed.

What causes excessive load on the rudder?

- Too much sail area aft. Sailing with main-only or a partially rolled-up genoa can do this.

- Over-trimmed mainsail.

- Excessive mast rake. Check the manual. Beach cats and planing skiffs have very specific reasons for radical mast rake. It only translates into more speed or better handling if the boat was designed for it.

- Excessive heel or bow-down trim. The hull form itself can force a turn to windward. A deeply buried bow can act like a forward rudder.

Centerboard trim

There are ways to fix these tendencies. Ease the main or lower the traveler. Reef the main and the headsail in balance. When sailing off the wind, it is often better to reef the main before the jib, to help keep her head down. Rake the mast to spec. Sail the boat flat. Bear away in the puffs when sailing deep, before the boat begins to heel excessively. Always steer for balance.

However, a centerboard or daggerboard adds an additional trim tool that is often forgotten. When the centerboard first begins to swing up, it moves more aft than up. In fact, a centerboard that is half up has typically lost only 20 percent of its draft and 15 percent of its projected area. On the other hand, the center of lateral resistance (CLR) on a 4-foot centerboard has moved aft about 1½ feet.

What about the change in righting moment of a weighted board? You have lifted it no more than 15 percent of the distance to the waterline, and depending on the board’s maximum depth, you’ve probably lost no more than 10 percent of the board’s contribution to righting moment. Don’t lift a weighted board more than this under sail, but experiment with how a slight movement aft changes things. Always mark the pendant so you know how far you have lifted the board.

Rising windspeeds

Consider the case of our Corsair F-24 test boat. As the wind rises, we might furl the jib for easier sailing. Reefing the main gives better balance, but rolling up the jib is easy and eliminates handling a whole set of sheets. Unfortunately, the sail center of effort (COE) then moves aft three feet, badly overloading the rudder.

In this situation, sailing becomes sluggish and we get trapped in irons every single time we try to tack. And there is no escape from irons, because even when we back the boat out as far as possible by reversing the rudder and fully easing the main sail—as deep as a beam reach—the moment we attempt to sheet in to make way, the bow swings right back into the wind.

However, if we lift the centerboard halfway, the center of lateral resistance moves aft about 1½-feet with very little change in area. We have less sail up, so the loss in area does not significantly increase leeway. The rudder will still be slightly overloaded and successful tacking requires easing the mainsheet as the boat comes through the wind, but you won’t be trapped in irons and the boat accelerates well as the main is slowly brought in. The rudder angle remains a little higher than normal, but it isn’t a brake.

Reaching in Strong winds

Strong reaching conditions are another time when centerboard adjustments help. When the wind gusts, the boat heels, and the resulting submerged hull form wants to turn to windward. In the case of a multihull, the lee bow digs in, acting as a forward rudder. The helmsman tries to bear off, but the rudder stalls and the boat swerves to windward anyway. Apparent wind accelerates, flow over the sails becomes better attached (reaching sails are often partially stalled, so rounding up attaches the flow), apparent wind increases, and power increases dramatically, just when you don’t want it. Centrifugal force from the rapid turn adds to the mess. A monohull will broach. A multihull can capsize.

The solution? First there are the standard solutions. Reef the mainsail early and fly more headsail; this will help keep her head down. Bear off early and smoothly before the boat heels excessively rather than waiting until the need is urgent. The earlier correction is actually faster, because the rudder angle relative to the water stays low, keeping drag low.

But also consider lifting the centerboard halfway or a bit more. Because there is little side force from the sails when reaching deep, you don’t need as much area. The boat will probably be moving faster through the water relative to the side force, generating more lift with less area. But don’t lift it all the way up unless the boat has a stub keel; you still want some board down as a leverage point for steering. The goal is to move the center of effort aft, so that the boat doesn’t want to round up.

You cannot adjust a board under load. If you apply enough force, you will only break something or hurt your back. Even if there are slides and a sturdy tackle, only adjust the board when traveling straight upwind or downwind, slowly if possible. This will reduce the load. Sometimes shooting straight into the wind for just a few moments is enough; quickly make the adjustment and then return to your original course.

Conclusion

Centerboard adjustments are not just for racers. It is a cruiser adjustment, just like reefing, for those who value good handling and safety. It’s all about balance, and by swinging the board aft just a little bit, you can cure certain handling problems.