The word “drudging” can be traced to the middle-English word for dragging. It is the practice of using a chain, heavy weight, or anchor on very short scope to control the motion of a boat while maneuvering in harbor.

There will come a day when your engine has quit and you need to enter a marina. Or perhaps your engine is working fine, but there is a combination of wind and tide that cannot be managed by engine and shorelines alone. Possible solutions are as numerous as the situations.

Dinghy Tow

If you have an inflatable tender with a sturdy engine, the most practical solution is often to use it like a tug boat. On smooth but open water, use a long nylon towline to reduce surging loads. For close-quarter maneuvering, lash the tender to the after quarter, steering with both the main rudder and the dinghy outboard. This is common practice for marina work crews any time a boat must be moved for service or hauling.

Never Force a Landing

One of the most important rules of docking is never to force a landing that you don’t feel good about. The dockmaster on Chincoteague Island, Virginia, directed me to slip between pilings, in spite of a 3-knot current running at 90-degrees to the slip. I looked at the slip, thought about it at length, and decided because the slip was a tight fit (only 18 in. wider than the boat) and my crew was limited, any attempt to enter the slip and control motion with ropes would be dangerous.

I chickened out and tied up to an adjacent bulkhead that was parallel to the current, easily warping the boat alongside and tying up without impact. I felt both guilty and incompetent as I watched a boat slide into the slip 15 minutes later. Thirty minutes after that, I walked up the dock on my way into town, and noticed that the boat had scraped off a 2 ft. x 8 ft. area of paint, the worst dock rash I’d ever seen.

Later on the same cruise, I was directed to tie up alongside a floating bulkhead with the tide running strongly underneath it. With twin engines, I had no difficulty working my boat into a parallel position, but I underestimated how the current would grab the keels and move the boat sideways, inexorably toward the dock.

We slammed into the dock sideways at more than a knot, with the full force of the tide pressing on both keels. Thank goodness for fenders, a strong hull-to-deck seam, and sturdy rub rails. This would’ve seriously dented many boats.

Observations

If you think a docking situation calls for drudging, here are some things to consider as you plan your approach (or departure).

Drag Factors

Obviously, the resistance will vary with the shape of the object being dragged and the type of bottom.

Chain

We’ve dragged lengths of chain along mud and sand bottoms. The friction amounts to about 0.4 to 0.7 times the weight of the chain actually on the bottom. Any chain that is suspended as catenary does not contribute to friction. We also tested dragging a loop of chain.

Depending on the distance the ends are separated, drag increases 0.6 to 1.0 times the weight of the chain, unless of course the chain snags on a rock or old wreck, which happened a few times. In each case we were able to recover the chain by releasing one end. Assuming 5/16-in. chain and that only 50 ft. are dragging on the bottom, this will provide about 35 lb. of drag, or similar to the effect of applying about 1.5 horsepower in reverse.

This tactic is only good for slowing a boat in lighter winds.

Kellet

Same rules as chain, only it is more likely that the entire weight of the kellet is bearing on the bottom, so long as there is reasonable scope (at least 3:1). The drag will be about equal to the weight of the kellet, depending on shape and bottom. Like chain, but useful in more wind.

Anchors

Here’s where things can get hairy. A pivoting fluke anchor that has not set will act like a poor kellet. You won’t even feel it. An aluminum Fortress will need some chain and rapid release of slack to keep it from planing along and never reaching the bottom. A pivoting fluke or new generation anchor that sets will stop the boat right where it is.

It also depends on the bottom. A new generation anchor dragged at 3:1 scope through soft mud will dig in a little bit, but not go deep enough to generate any real holding. With the chain leader, the same anchor might bite hard in sand, while with the rope leader it might not bite at all.

Plow and claw anchors, on the other hand, are more able to drag predictably on short scope without actually setting. But notice that everything we said above is full of caveats. On any given day, with a different rode combination, slightly different scope, and different bottom type, the anchor that very predictably provided 100 lb. of drag yesterday, may now either slide along with no discernible restriction, or set hard and stop the boat.

An anchor can be dragged backwards. If the rode is attached to a tripping eye it behaves much as a kellet, described above. Of course, you have surrendered the option of converting it to an anchor by increasing scope.

Evaluate the Situation

Even if the engine is functioning, never feel you need to land on the first pass. Very often, when entering a new marina I will intentionally motor past the assigned space in order to get a good look at the space, what I might hit, escape routes if the approach is blown, and a look at the local wind and tide. I might make several passes until I have at least two plans in mind and discuss them with the crew.

If the engine isn’t functioning, anchor out and take the dinghy over to have a look. Watch how the tide moves the dinghy. Figure out where you can get lines on to control the motion of the boat. Will it make sense to drag something, or set an anchor either during the approach or with the dinghy that you can use as an additional control line?

No amount of extra rigging effort will look as silly as crashing into something. Don’t feel that using a drudge or anchor as an aid to getting into a tight spot is unnecessary just because you have an engine. Finally, reserve the right to refuse any slip or bulkhead that feels unsafe. I’ve turned down many slip assignments.

Sails

In many cases it’s perfectly safe to sail right into the slip. I’ve done this a number of times in my own slip, comfortable with an intimate knowledge of local conditions and the maneuvering characteristics of my boat.

I am always prepared to immediately anchor or slow down and grab a piling if something changes or if traffic prevents necessary maneuvers. Don’t hesitate to use the horn, but don’t expect that anyone will listen; they may not recognize that you are in legitimate distress, assume you’re just a stupid sailor showing off, and not understand just how restricted your maneuverability truly is.

Anchoring can be an emergency situation, even in a harbor. Several years ago I headed out for an afternoon sail, after ticking off a few boat tasks. A hundred yards into the passage between the

entrance jetties, one of the engines conked out. I tried the key and it wouldn’t even cough, but I reasoned it was just a minor warm-up problem that I would sort out in a few minutes once I was in open water. Unfortunately, its twin conked out less than a minute later, just short of the exit. There was a brisk 25-knot crosswind and I calculated that by the time I fussed with restarting them I would surely be on the rocks. The solution was to anchor immediately; there was enough room and time if I executed every step correctly and expeditiously.

- Momentum. The boat was still moving forward at 5-6 knots, providing me considerable latitude to coast into an advantageous position. If I had wasted time puzzling out why the engines stopped, I would have drifted too close to the leeward jetty for anchoring to be an option. Instead, I took advantage of what momentum I had to maneuver the boat as close to the windward jetty as practical. Act quickly, because momentum won’t keep. Each time you anchor, note how far your boat carries into the wind, until you create a database covering a range of conditions.

- Quick Deployment. In harbor settings the anchor should be ready to go within a matter of seconds. Any lashings for offshore sailing should be removed and the anchor should be secured by only a quick-release pin or simple lock. Because I had only to remove a spring clip and pull a pin, I was able to calmly walk to the bow and release the anchor before the boat began drifting backwards.

- Scope. While it’s tempting to begin snubbing the rode at short scope to see if the anchor is catching, resist the temptation. Nothing more than the lightest hand setting should be attempted until scope is at least 7:1. Remember, you’re in a harbor and it’s probably shallow, so it won’t take that long to achieve 7:1 scope. You want it to set and hold the first time. Allow for rode stretch and setting distance.

I was singlehanding, as I often do, but that didn’t make a difference. Anchoring should be a one-person job, where no two actions need to be performed at the same time. Practice until you can do it quickly, without preparation.

I was anchored squarely across the channel, but it was a weekday without traffic. Once satisfied that the anchor was holding, I was free to focus on the engine problem. I lifted the port engine cover and within moment suffered a classic face-palm moment; when I changed fuel filters that morning I forgot to re-open the filter isolation valves. The gasoline in the carburetors and line was just sufficient to propel me between the jetties. Always run the engines for 10 minutes after any engine work, no matter how simple, before heading out!

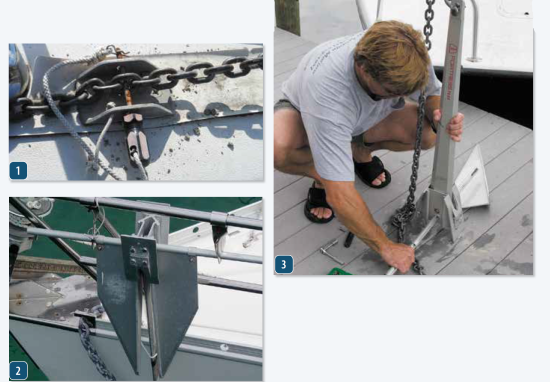

2. This Fortress is ready to deploy, but unfortunately, this style of anchor is a poor brake, since the design tends to ‘plane’ if you are moving too fast.

3. Assemble adjustable-fluke anchors to match the bottom long before you need to use them.

Several years later I backed out of a slip in a small fishing village, right into a mess of floating fishing gear that had just drifted behind the boat, tangling both props. I didn’t have a lot of time, probably only 30 seconds, before the 2-knot tide swept me into a row of boats. However, there was enough time to throw the rudder hard over to spin the boat 90 degrees, walk to the front of the boat, and lower the anchor. After drifting 100 feet, I gently snubbed the rode, checked for holding, and went for a quick swim (tricky in such current) to unwind the ropes. Another tragedy narrowly averted.

I often see boats with an anchor on the stern rail. Many are used for fore-aft anchoring, but a good many believe that if the engine fails, this is also their emergency brake. In practice, it may not work. First, you probably won’t have enough distance. Better, use your momentum to coast in a direction of safety. This will also slow the boat. Second, the anchor is not going to catch and hold if you have any significant way on.

A pivoting fluke anchor might plane and not even reach the bottom, and others will just drag at speed. If by some miracle it did catch in the soft harbor muck, the impact force will be immense, on the order of hurricane loads, and the anchor will then drag. PS testing has shown that boat speed over 1.5 knots exceeds the safe working load of chain rode, and a boat speed over 3 knots exceeds the safe working load of rope rode. In both cases, the holding capacity of a newly set anchor will be severely taxed.

Dropping the bow anchor with even a slight turn of the wheel is better; the boat will “club haul,” pivoting within its own length, the turning action dissipating considerable energy. If the situation is really tight, sometimes the best plan is to coast within grabbing range of a windward piling. Get the boat stopped with a quick turn, and place fenders where protection is needed. Now you have bought yourself time to work out a proper solution.

The important thing in each of these examples is that you are stopped, the result of maintaining situational awareness and using stored momentum.

The Basics

Slowing the Boat

If there is a following wind and the boat is simply blowing in the channel too quickly, try a long length of chain first, perhaps with a kellet, but have an anchor ready.

Turning the Boat

The rudder is typically ineffective at very low speeds; 2-3 knots is the minimum, depending on the boat. However, the boat can be turned either quickly or slowly by lowering an anchor off one side.

Lowering the anchor from near the midship cleats and dragging lightly creates a gradual turn. Lowering the anchor further and allowing it to bite, whether from the midship cleats or bow, creates an abrupt turn and stop, through a practice known as club hauling.

Allowing the anchor to bite and securing it to a midship cleat will hold the boat at 90-degrees to the wind or tide, depending on which is of the two forces is controlling the movement of the boat.

Stopping the Boat

Often it is possible to convert from either slowing or turning the boat by gentle dragging of an anchor, to stopping the boat entirely. Let the rode run free for 100 ft. so that the anchor can set, and then slowly snub the rode around a cleat until the boat is stopped. The snubbing can be very gentle if all you intend to do is slow down.

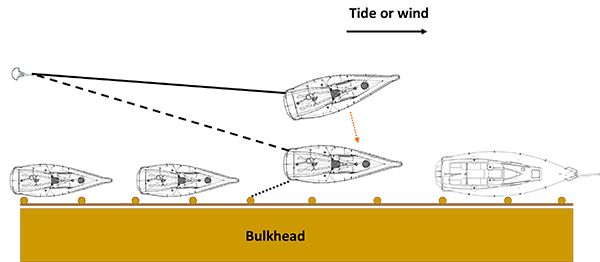

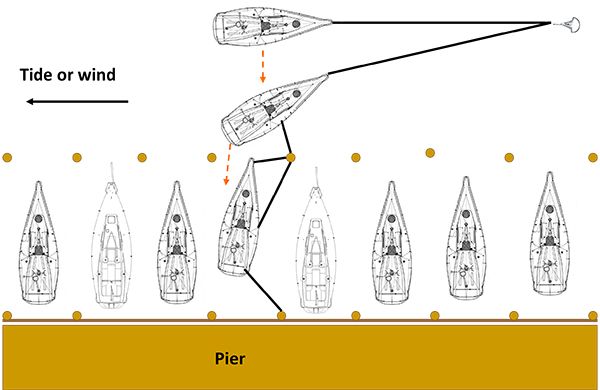

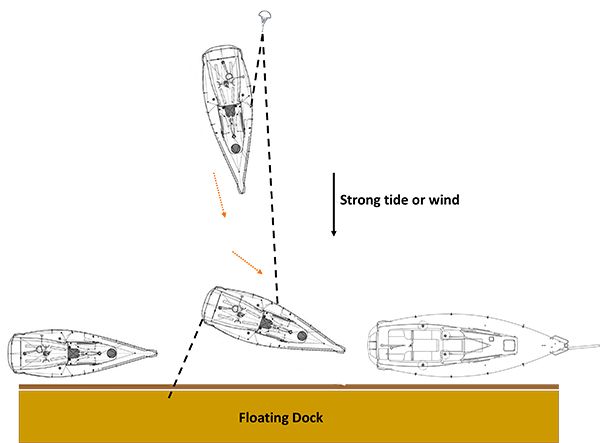

The accompanying illustrations show the various situations in which “drudging” can be put to work. Some of these, I’ve put to use on more than one occasion.

- Stopping on a long bulkhead. You may be able to sail parallel to a long open section of bulkhead using the genoa, but then there is the matter of stopping. Only a small bit of sail should be used, and that will be let free or doused some distance from the bulkhead. Dragging a chain, kellet, or anchor will stop the boat, the choice based on the amount of wind and weight of the boat. Too much is better than too little.

- Sailing into a slip. First, be realistic about the conditions, your ability, the crew on board, and the situation. I have sailed right into my slip several times, but only with intimate knowledge of my boat, the surroundings, and in perfect conditions. Another time the conditions were not perfect (too much wind), so I anchored very close to the slip and used two lines looped around pilings to warp the boat in singlehanded (see illustration). It took 20 minutes, but went smoothly and without strain.

- Floating Dock. Having learned my lesson about tides running under floating docks, I was more cautious the next time I was faced with this situation. My engine was operating just fine, but the slot was only about 10 feet longer than my boat and I feared the tide slamming me into the dock again. The solution was to lower an anchor off the non-dock side while still about 100 feet from the dock. The rope rode was turned loosely around the mid-ships cleat. As per usual, I maneuvered the boat parallel to the slot, while at the same time a crewman controlled slack in the anchor rode. As the tide began to push the boat sideways, the crew firmly snubbed the anchor line while I jockeyed the throttles to keep the boat parallel and centered in the space. In fact, we left the anchor line in place over night, since a storm was approaching and a beam anchor would help hold us off the bulkhead if waves built.

Conclusion

Plan ahead. None of this is complicated, but putting it together under fire is a recipe for disaster. Try some of these methods in the open to learn how your boat responds. When a challenge arises, take as much time as you need to work out a safe solution. Back in the day maneuvering by oar, anchor and warp was common practice.

This article was published on 22 April 2021 and has been updated.

What is best solution for removing rust stains from stainless steel plate.

Please see the July 2020 article, “Passivating Stainless.” Formulas based on citric acid, including Spotless Stainless, Cirtisurf, and DIY versions, tested best.

Some very clever docking techniques, but….. once you are safely tied to the pier, you have the anchor to deal with. If it’s windy/tidal flow enough to need the described technique the anchor/rhode retrival will be a in my mini sized dinghy!

The only times I have used these methods (twice in over 40 years) were with dead engines (one was a delivery, the other was a rope that spun the prop). I could have gotten a tow within an hour in the first case, but it would have been the next day in the latter. In both cases, with a little planning, a safe, calm, bump-free docking was achieved. Yup, I had to dinghy out to get the anchor.

Beg to differ on the dinghy tow at length idea. Experience has shown that you can’t maneuver a large craft with a smaller one the end of a rope. The difference in mass of the two vessels results in wild and unmanageable results. It is recommended to only using a dinghy as a taught tied tow boat. Side tie works well, away from the exhaust port. Let the big boat manage the steering.

Barges and yachts are commonly towed in open water. The mass difference can be enormous and the tow operator must understand the effects of wind, waves, and momentum. The cable is long. They switch to pushing or side lash for harbor maneuvering. Different things.

So we were rafted alongside in Horta. Our engine was out of the boat. Early one morning one of our raft mates, the boat closest to the cay decided to leave for Europe. So they untied and slipped out. Leaving the four out board boats that had been tied to them drifting through the marina. As we scrambled on deck each boat started their engine and broke up the raft. Our pleas in English were not well understood by our Finnish neighbors. They slipped our lines waving and smiling. If we did not have an anchor on the ready we would have damaged several vessels. I let run as long as possible and snubbed up with inches to spare.

We have often left an anchor set out in deep water when beaching our shoal draft boat in Florida.

Using an anchor to approach a dock seams unconventional today but is a classic old school tool we should all remember is available.