Photos courtesy of Tom Curren

The Alberg 35 dates back to the dawn of big-time fiberglass sailboat building. Its production began in 1961, just a year after Hinckley stopped building production wooden sailboats. Two years earlier, in 1959, Pearson built the first Triton, the boat that was the prototype of the inexpensive, small family, fiberglass cruising sailboat. The Tritons big selling point was a low-maintenance hull that Mom and Pop and the kids didnt have to spend all spring in the boatyard, getting it ready for the summer.

These days-when getting the family sailboat ready in the spring may mean little more than washing and waxing the topsides, plus a quick coat of paint on the bottom-its hard to remember that owning a boat some 30 years ago usually meant work, and a lot of it, or money, and a lot of that, too.

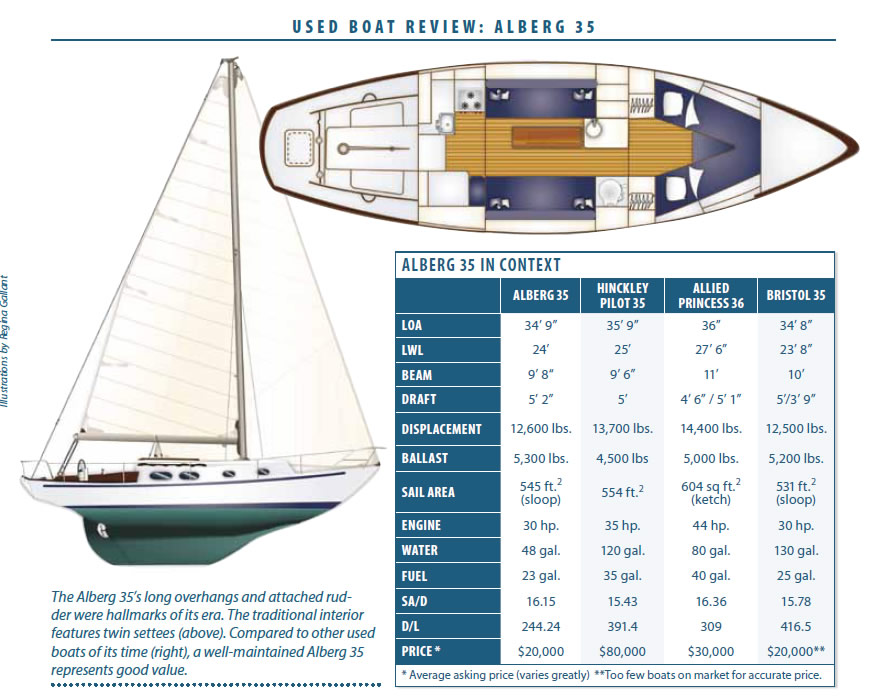

In 1961, Pearson added the 34-foot, 9-inch Alberg 35 to its expanding sailboat line. The Alberg 35 was a fixture in the Pearson line until 1967. In 1968, the boat was replaced by the Shaw-designed Pearson 35, a slightly larger, more modern boat in keeping with the changing demands of the market. During six years of production, more than 250 Alberg 35s were built.

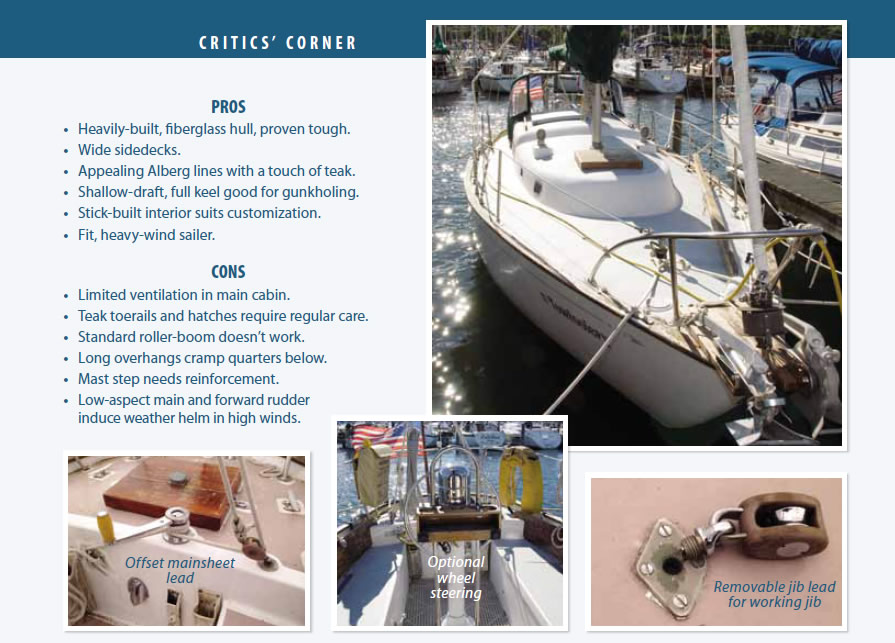

Its very tempting to call every good-looking, successful boat from the 1960s a classic. And the Alberg 35 is no exception. It is good-looking and was successful, so we think it deserves to be called a classic. The boat has a handsome sheer, flattish for her day but old-fashioned and springy compared to current boats. She has a low, rounded cabin trunk with slightly raised doghouse, and just about perfectly balanced long overhangs both forward and aft.

Compared to more modern 35-footers, the Alberg 35 is narrow, short on the waterline, and cramped. Todays typical 35-foot cruiser-racer is at least four feet longer at the waterline and more than a foot wider.

Sailing Performance

The term cruiser-racer was just entering the jargon in 1961. The Pearson sales brochure from 1967 calls the Alberg 35 a proven ocean racer, cruiser. Note the term ocean. The Alberg 35 was the smallest boat in the Pearson line to which that word was attached, unlike many builders who push anything with lifelines and a self-bailing cockpit as a bluewater cruiser.

While the Alberg 35 had moderate success as a racer, the boat was-and still is-a cruising boat. By current standards, the Alberg 35 is a slow boat for her length overall, with a typical U.S. Performance Handicap Racing Fleet (PHRF) rating of 198. By way of comparison, her replacement, the Pearson 35, rates about 174, and the Ericson 35-2 about 150.

But Alberg 35s take to sea pretty well. The narrow, deep hull form makes for a very good range of positive stability-about 135 degrees-and an easy motion in a seaway. Owners consider the boats speed on par with other boats of similar size and type.

Unlike modern boats with wide beam and firm bilges, the narrow Alberg 35 heels very quickly, despite a 42-percent ballast-to-displacement ratio. But narrow boats sail fairly efficiently at fairly steep heeling angles. A modern boat such as the J/35 sails best upwind in 15 knots of true breeze at a 23-degree angle of heel, while a boat like the Alberg 35 is happy at close to a 30-degree angle in the same conditions. (Bottom line: The cook will insist that you crack off while supper is on the stove.)

With a rudder set well forward, it can take a lot of helm to keep the boat on course when reaching in a breeze. The relatively large, low-aspect ratio mainsail doesn’t help. At the same time, owners report that the boat tracks well, a quality missing in many newer boats.

The Alberg 35 was built both as a sloop and a yawl. Yawls were popular under the Cruising Club of America (CCA) Rule because mizzen and mizzen staysail area was lightly taxed. The yawl is not a bad rig for short-handed cruising, since the mizzen can be used to help balance the boat, and it is particularly useful in anchoring and weighing anchor under sail. From a performance and handling point of view, however, the yawl rig has few if any advantages on a boat this size. We would look for the sloop rig if we were shopping for an Alberg 35.

The mast is stepped on deck, over the doorway to the forward cabin. This requires substantial reinforcement of the bulkhead. Several owners in our survey reported that the coring in the deck under the mast has crushed, allowing the top of the cabin to compress. The problem can be fixed by replacing the core with solid laminate, and re-locating the compression post more directly under the mast. Other owners have also laminated in cross beams beneath the deck to reinforce this area.

Both the sloop and yawl rigs have simple, fairly heavy aluminum masts. A varnished spruce roller-reefing main boom was standard. Wed forget the roller reefing and set the boat up for slab reefing. In our experience, a roller-reefed mainsail is usually so baggy that its useless for upwind sailing.

Several owners in our survey have added bowsprits to their A35s, converting them to cutter rigs with a yankee and staysail. This improves the boats balance, as well as making sail combinations more flexible for cruising.

The cockpit is long and quite large, with plenty of room for daysailing hordes. Cockpit coamings are teak, and really look nice when varnished. The standard tiller takes up a lot of cockpit space, but most boats weve looked at have the optional pedestal wheel steering.

Big port and starboard cockpit lockers have poor locking arrangements, and drain straight to the bilge. Give a lot of thought to what will happen if the boat is pooped by a following sea, then go to work at improving hatch sealing and fastening.

Sail-handling equipment on these boats is likely to be primitive. The old Merriman No. 5 genoa winches and No. 2 mainsheet and jib halyard winches date from the time when trimming and setting sails was expected to be a lot of work. Wed replace them all with modern, powerful, self-tailing winches if anything other than daysailing is contemplated.

Likewise, there was originally no mainsheet traveler. On a narrow boat like this, with the mainsheet led aft, there really isn’t that much advantage to a traveler; it simply operates over too small a range of the booms arc to offer much benefit. If the mainsheet were re-led so that you could put a traveler on the bridgedeck, just in front of the steering pedestal, a traveler would be worthwhile. This, of course, would mean getting rid of the roller-reefing main, but in our opinion, thats a good idea anyway.

Wheel steering was an option, but youll find it on a lot of Alberg 35s-a plus, in our opinion.

Construction Details

Today, many A35s are used for offshore cruising. Plain, rugged construction is one reason why. The hull is a heavy, uncored layup, not particularly stiff or strong for its weight, but easy to repair and relatively foolproof.

Rudder construction is a holdover from the days of wooden boats. It consists of a wooden rudder blade bolted to a heavy bronze rod, formed to the shape of the aft edge of the prop aperture. The rudder of any Alberg 35 should be examined carefully, not because this type of construction is poor, but simply because the rudders are getting old. The rudders may have been damaged in groundings, or the stock bolts may be corroded.

One advantage of rudder construction is that it is very easy to change the rudder design. We suggest getting rid of the original barn-door rudder blade and replacing it with a more modern design with a straight trailing edge and more area near the bottom of the rudder.

This Constellation-type profile became pretty much standard with the last long-keel CCA boats designed before the Intrepid-type skeg and rudder of the late 1960s. The bottom of the new rudder could be angled up slightly to reduce the chance of damage in groundings.

Two aspects of the boats construction have caused some problems for owners. First, the ballast casting is a single chunk of lead which is dropped into the hollow fiberglass keel molding.

Along the bottom of the keel, some boats have a void between the lead casting and the fiberglass shell, making the shell vulnerable to damage in groundings or even when hauling and launching the boat. A surveyor should carefully evaluate this area for voids by sounding with a mallet. Voids can be fairly easily filled by injecting epoxy resin into the cavity.

The other problem could be more difficult to solve. The decks on early fiberglass boats like the A35 were frequently built using edge-grain rather than endgrain balsa wood. Edge-grain lacks the stiffness or compression strength of a modern end-grain balsa sandwich. Flexing of decks cored this way can break the bond between the fiberglass skins and balsa core. If the deck feels mushy, it likely is at least partially delaminated.

Repair-assuming the core is dry-involves drilling an extensive network of holes through the deck skin and core, being careful to reach but not penetrate the inner skin. Epoxy resin is then injected in each hole until it runs out of adjacent holes. The deck should be braced upward from below and weighted down from above until the resin cures.

This method works well with small areas of delamination, but is a tedious job in larger areas. At best, you end up with a deck sandwich that is somewhat stronger than the original that failed. Major refinishing of the deck will then be required. Extensive deck softness is cause for rejecting any boat, regardless of age.

You will find a variety of tankage arrangements in boats of different vintages. According to one owner, early boats have galvanized fuel and water tanks, which will eventually rust through. Another owner had a huge built-in fiberglass fuel tank forward, which developed a leak and was replaced by a monel tank in the same location. Design specifications for late boats in the production run call for an integral, 48-gallon, fiberglass water tank located in the bilge under the main cabin sole, plus a 23-gallon monel fuel tank under the cockpit sole.

The advantage of the monel fuel tank is that it will not have to be replaced if a diesel engine is installed: Simply flush it thoroughly with diesel fuel to remove any traces of gasoline, and youre in business. Monel is absolutely the best material for either fuel or water tanks, but it is prohibitively expensive for most.

Like most sailboats of this vintage, you may find extensive gelcoat crazing and fading on both the hull and deck. This is a cosmetic problem up to the point where crazing allows water to migrate into the laminate, at which time it can become a structural problem. If the gelcoat has begun to buckle and peel, its best to avoid the boat unless youre looking for a boat at a rock-bottom price for offshore sailing. Cosmetic repair of superficial crazing is labor-intensive, involving sanding, multiple coats of high-build epoxy primer, and complete refinishing, preferably with polyurethane. To have this done professionally would be quite expensive.

The deck gear, standing rigging, and spars on these boats are getting old. Many of the boats have high mileage, since a large percentage are used for long-distance offshore cruising. Be prepared to do relatively simple jobs like removing and rebedding stanchions and deck fittings, installing backing plates, and replacing a lot of rigging. Sails more than five years old-other than storm sails that have seen little or no use-are candidates for replacement.

Engine

All Alberg 35s were powered by the ubiquitous Atomic Four gasoline engine. If youre thinking about keeping an A35 for five or more years, think about replacing the engine-preferably with a diesel.

Of course, a lot of owners have already retrofitted their boats with diesels, but the installations will obviously vary dramatically in quality.

The pluses and minuses of replacing an old Atomic Four with a diesel are still debated at length online, although the tenor is more subdued these days. Certainly, a boat with a smooth running Atomic Four will serve its owner well, but in our view, the scales are pretty heavily tilted toward a diesel conversion. Finding a boat with a defunct Atomic Four and putting a diesel in it is a sure way to increase the value, although as with most boats of this age-even classics like the Alberg 35-you cannot expect that you will ever get out of the boat what you invest in it financially, should you decide to sell. The big benefits for switching to diesel are safety and the fact that the cruising range under power roughly doubles-a big plus in light-wind areas.

Westerbeke, which bought the Atomic Four line from the original manufacturer, makes three- and four-cylinder replacements. Betamarine advertises itself as the only manufacturer dedicated to supplying diesel engine replacements for the Atomic Four. Whichever replacement you choose, don’t assume a drop-in replacement. You will have to double-check all your measurements. In many cases, an upgrade to diesel from an Atomic Four means youll need to get a new prop as well.

Like most boats with the rudder mounted well forward and the prop fitted in an aperture, the Alberg 35 backs down poorly. This is simply a fact of life, so you have to get used to it. Steering ahead, the boat handles fine. The Atomic Four provides perfectly adequate power for the A35, giving a cruising speed of about 6 knots in calm water.

Interior

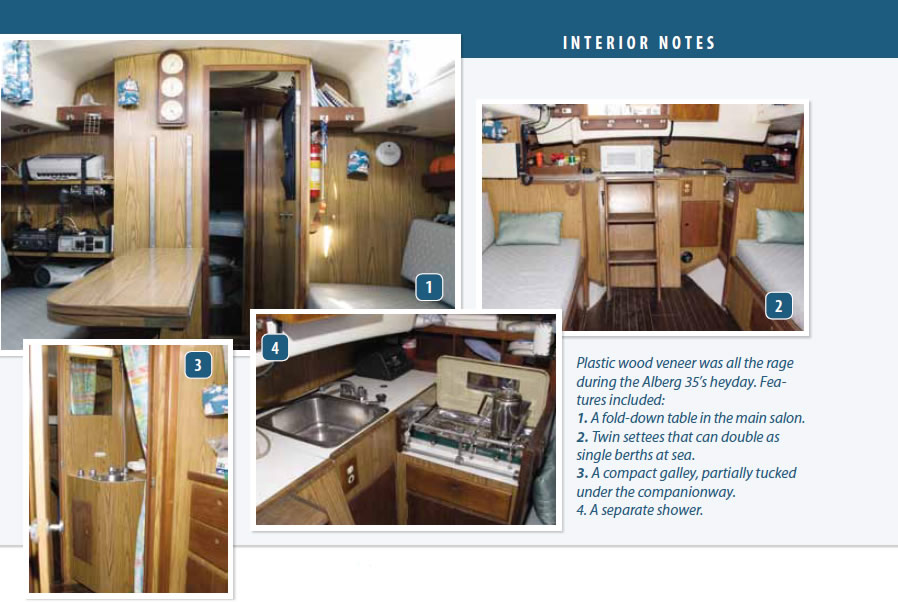

Because the Alberg 35 is narrow, it will seem cramped to those accustomed to the condo-like interiors of modern 35-footers. The arrangement, though, is pretty good.

Two interiors were built: One is the traditional interior of practically every boat built in the last 50 years, the other is a dinette arrangement, which became popular when people started looking for more workable galleys about 30 years ago. Both boats have large forward cabins with V-berths, a hanging locker, a bureau, and drawers under the berths. This is one reason the boat appeals to a lot of minimum-budget liveaboards. The forward cabin can be a real owners stateroom, even though it lacks a double berth. If you were handy, you could rip out the V-berths and build a good-sized diagonal double along either side of the cabin, building in additional storage opposite. The cabin is large enough that this wouldnt totally destroy standing space.

There are two bronze-framed opening ports and a hatch for ventilation in the forward cabin.

The head is aft of the forward cabin, and runs the full width of the boat-a good arrangement on a boat this narrow. With the doors to the main cabin and forward cabin shut, this creates a head compartment with a lot of elbow room. For daysailing, you only need to shut the door to the main cabin to get privacy-no worse than shutting the head door on any boat.

Ventilation is provided in the head via two opening ports plus a pair of cowl vents in Dorade boxes.

The Alberg 35 was one of the first boats of this size to be built with standard hot and cold, pressurized water, plus a shower. It was a big selling point back then; now it is taken for granted on a 35-foot boat.

The main cabin will have either the conventional arrangement of settee berths on each side with a fold-down table between, or the galley along one side with a U-shaped dinette opposite.

The dinette arrangement is a decidedly mixed blessing. By lowering the dining table, the dinette converts to a double berth. The original stove well in the dinette arrangement was big enough for a three-burner gimballed stove with oven, while the conventional aft galley has the rinky-dink two-burner alcohol stove that was standard equipment on most boats for many years.

With the dinette, there are two quarterberths aft that extend under the cockpit, and they are reasonable sea berths. In the conventional arrangement, you would use the main cabin settees as sea berths, which is also fine.

Quarterberths can be stuffy in tropical climates, and they tend to end up as inefficient catch-all spaces for anything that is too big or awkward to stow in lockers or drawers.

But the aft galley is no prize. The galley counters are quite low due to the boats low freeboard. There is a small single sink, plus the aforementioned instrument of torture in place of a stove, and an icebox whose top must perform double duty as galley work space and a rudimentary chart table. With the dinette arrangement, the dining table will probably double as the nav station, although wed be tempted to sacrifice one of the quarterberths to build in storage space plus a usable, stand-up nav station.

Its no wonder that at least one owner reports tearing out the entire aft galley and starting from scratch.

Ventilation in the main cabin is non-existent, except for the main companionway hatch. Because of the step in the cabin profile, fitting a ventilation hatch over this cabin is tricky, but it can be done.

Interior decor is very period, and the early 1960s were perhaps the nadir of interior design in sailboats. Low maintenance fever was at its peak, and wood-grain plastic laminate ran rampant.

Fortunately, this is nothing that a little painting can’t cure, or if youre really handy, you can laminate nice, clean, solid-color Formica over the old stuff on the counters and bulkheads, then varnish the wood trim. The improvement in interior appearance and apparent space would be amazing.

Conclusions

Weve presented a pretty intimidating list of drawbacks to the Alberg 35. Now lets look at the positive side. This is a sturdy, ruggedly built boat whose design and construction are suited for serious offshore sailing, with the caveat that you go through the boat from one end to the other, replacing every piece of gear thats tired, and reinforcing and repairing as necessary.

There are not too many boats that you can buy for this kind of money and then head off to Tahiti in reasonable security.

Built without the full-length molded fiberglass pans and liners that interfere with even modest modification, the Alberg 35 is stick built-a tinkerers dream. You may not be ready to build a boat from scratch, but you can do modifications on the Alberg 35 to your hearts content without going broke or destroying your investment.

The boat is really good-looking, especially compared to a lot of modern, high-sided tubs. If youre a fanatic, you can clean up, paint, and refinish the boat to look almost as good as a Hinckley Pilot-almost.

Some Alberg 35s have been meticulously maintained, and are in beautiful condition. Others have been beat to pieces by owners going cruising on the cheap. Wed look for a nice one, or one that had only cosmetic problems. The trick is figuring out which problems are only cosmetic.

A liveaboard couple can be comfortable on this boat, having much more elbow room than on a smaller modern live aboard cruiser for which youd pay more money.

You want a decent-sized boat for serious cruising, while spending about the same money as you would for a newer 27-footer? Consider the Alberg 35. Buy it, and be off for warmer places.