The following is aimed primarily at boats that are unable to leave an alongside dock or bulkhead before wind and seas become dangerous. Any fetch beyond 200 yards is dangerous, and there may be nothing you can do to protect the boat. However, if you are in a protected marina, well up a creek, and the storm is moderate, these actions can help. Just remember that low breakwaters will be overtopped, wooden breakwaters fall apart, other boats will come loose, and there will be lumber in the water from broken docks.

Photos and illustrations by Drew Frye

General

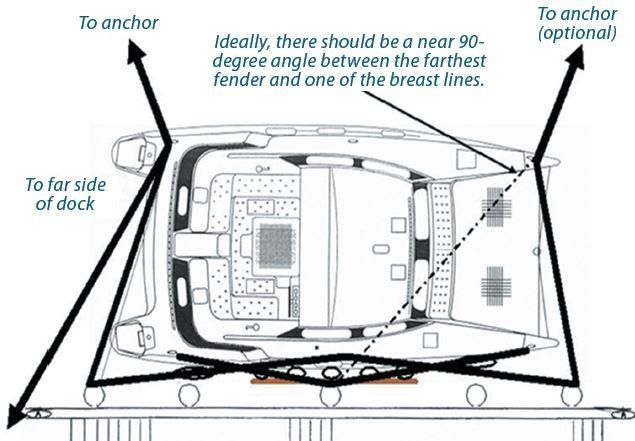

Spring Lines. Run two sets, using mid-ships cleats or bow and stern cleats (the inboard stern cleat should be available). Spring lines should be as close to parallel to the dock as practical. Many patterns are possible, influenced by the availability of deck and dock cleats.

Breast lines. Use both perpendicular breast lines and narrow-angle fore-aft lines. This will reduce motion and provide redundancy. Consider running these to the far side of the dock to allow more length for surge, but pay attention to chafe on the dock edge.

Variable lengths. Redundant breast and spring lines work best to reduce motion, strain, and control bouncing on the fenders if they are all different lengths and angles, secured to different points. Often a single line at a different angle can damp a damaging cycle.

Don’t overload cleats with lines. Because you will need to place multiple lines on one cleat, consider using loops and placing hitches at the shore end.

Fenders. Add extras behind the boards. We use as many as four behind the boards.

Surge. If the tidal surge will reach within five feet of the piling tops, you need to leave. You will lose the boat if the tops get below the rub rail and fenders. This rules out most bulkheads in cyclones and severe low pressure events.

Don’t get under the dock. If a fender (or worse, the deck) gets under the dock face due to rolling or extreme low tide, something is going to break.

Lay an anchor or two off the beam. These can make all the difference if waves become too much for the fenders. However, the anchors will drag toward the dock as forces increase and they set more deeply, and slack will change as the tide changes, possibly creating greater pounding than without.

The anchors will need frequent tending, and pulling may be impossible, even with a winch. If the rode is chain, add a rope snubber using a soft shackle through a link-nylon will absorb shock and help maintain tension. Secure the rode to a bollard or cleat. The winch should not bear any load. Do NOT run the bow anchor through the roller on the bowsprit.

Allow for stretch. Lines will stretch as much as 5 percent under loads of 10 percent of breaking strength.

Reduce windage. Stripping sails and canvas always helps, particularly furling headsails and storm cloths. Take the dinghy off the deck and store on-shore.

Pilings

Fender boards are required. These should be long enough to stay in position; 5 feet is handy for storage and is enough under normal conditions, but 6 to 8 feet is much better. The suspension lines must be positioned so that they cannot become pinched and cut. Although two large fenders no more than three feet apart are sufficient under normal conditions, inserting additional fenders during storms helps spread the load on the hull, provide redundancy, and reduce bending force on the board. Avoid plastic and synthetic lumber-its not strong enough. PVC pipe might be strong enough for a smaller boat, but it does not have enough bearing surface to spread the load across the fender.

Multiple fender boards are recommended. Fenders alone can push out of position and breast lines will be stretched. Fenders hung horizontally may stay in position in fair weather, but when the wind kicks up they can pop out.

Securing fenders. Don’t hang the fenders or fender boards from the lifelines unless you like bent stanchions. The forces can be enormous if they get stuck under a dock. Toe rail or stanchion base attachment is much better, if possible.

Fixed concrete facings

Fender strings. Fender boards tend to hang up, and there are no pilings for them to follow above the top of the dock. Instead, thread two large fenders on a single vertical line (Taylor Made Big Bs work well). This will create a very long fender that can slide up and down a rough face. Their weight is enough to keep them down and prevent excessive rolling, though they move well with the motion of the spring lines, minimizing chafe.

Redundancy. Bulkheads can be very rough. Use at least three of these fender strings.

Sizing. Go up one size in fenders from standard recommendations. The strings work better this way.

Floating docks

No tide. Only minimal slack is required to allow for some differential movement.

Piling height. The basic spring and breast line set up described for bulkheads is still valid for floating docks.

Lots of fenders. If you used enough fenders, fender boards are generally not required.

Storm surge. Confirm that the surge cannot lift the docks above the guide pilings. We’ve seen this happen, and it’s bad.

Line sizing. Lines should be sized such that they will not fatigue or heat, which generally requires sizing to match loads of less than 1/12 the rated breaking strength. The longer the line the more area available to dissipate heat; it is most often the short lines that break. Rhythmic bouncing is bad.