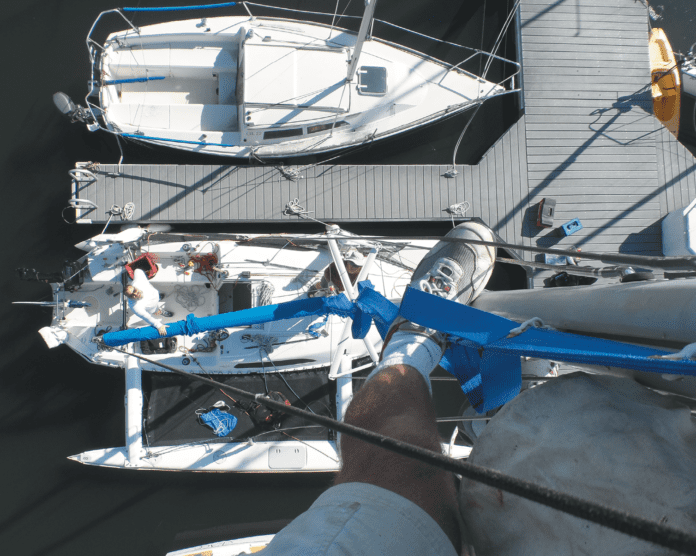

As mooring and maintenance fees skyrocket, joint boat ownership can seem like an attractive way to contain expenses and still enjoy all the benefits of having your own boat. For the past several years, I’ve been a satisfied co-owner in a Corsair F-24, but the arrangement does involve compromises that not every sailor is prepared to make.

Consider the options. If you aren’t planning to do a lot of sailing, bare boat chartering, fractional ownership and peer-to-peer programs can make more sense (see “Learning to Share,” PS January 2006, and “Share Economy Goes Boating,” PS July 2015). You get time on a boat while spreading out the costs and headaches associated with ownership.

Choose the right partner. Look for people who have owned boats before and have some do-it-yourself skills, otherwise be prepared for some hefty yard bills. A shared boat should not be the first boat for either partner.

Formalize an agreement. Even low-priced boats shared among friends will benefit from clear terms of ownership. If you have boat loan, or a higher-priced boat, explore the possibility of creating a limited liability corporation (LLC) (see Tech Tips on p. 22).

Share the work. It’s very likely that one or more partners simply won’t be available to work on the boat. Perhaps you use the boat more. We have a partner that uses the boat very little and does not participate in the work; that feels fair. If you are hung up on having a perfectly “fair” division of work, you might not be a good candidate for a partnership.

Agree on the right boat. A classic partnership agreement is one to that defrays the higher fixed costs (marina fees and maintenance) on a low-cost boat. With little capital risk, the partnership can dissolve without overburdening the remaining owner. Ideally, the boat should be one that is easy to use, fun to sail, and aesthetically attractive to all owners. Day sailors, modest cruising boats, and racing boats are good contenders for partnerships. Avoid fixer-uppers.

New boats vs. used boats. New boats depreciate fast, violating the “keep-it-affordable” rule. New boats have less maintenance, but concern over minor dings and resale value can cause major friction.

Smart scheduling. Scheduling is tough for working folks, especially those with school children. If that’s your situation, look for a retired or semi-retired partner who might prefer sailing in the spring and fall. Perhaps you have flexible work-from-home employment.

Use vacation time. In places with short sailing seasons, your allotted boat time can evaporate quickly. Try to schedule vacation during times when good winds and fair temperatures are most likely.

Crew or partner? Some folks assume a partnership means that the owners will sail together and that each partner has a commitment to be available as crew. That’s a great situation, but you should be prepared to sail with crew of your own.

Scheduling and tracking use. A shared calendar or document on the cloud can help manage projects, expenses, and scheduling (see “Online Crew Management,” PS April 2021). In addition to an onboard log on, my partner and I also have an Excel spreadsheet with separate tabs to track routine tasks.

Kids and boats. For a family that likes to sail together, ownership is often the better choice. Kids can get their own cabin and decorate as they please. On the other hand, if family activities keep you away from the boat, a partnership might be a sensible way to defray costs. In either case, your co-owner should be okay with any kid-friendly modifications (side-nets, extra handholds, stuffed animals in the v-berth, etc.)

CONCLUSIONS

Only enter a partnership if you can easily afford to buy and maintain the boat on your own. If you buy a boat that neither partner can afford individually, it increases pressure on the relationship. Instead of partnering with friends, consider partnering with a like-minded sailor. They are more likely to understand the commitment and vagaries of boating and might well become friends.

Expect there to be more work and expense than you’d anticipated. If you are obsessed with doing things your way, don’t get into a partnership. Consider partnering with people that have owned a similar-sized boat before; they will understand what they are getting into.

Successful partners that we’ve studied view the arrangement either as a business, with strict adherence to the written agreement and legal conduct, or as a marriage, with the understanding it will require flexibility and compromise. In both cases, success was measured by whether it was better than the alternatives, not against a fantasy. If you like company, sharing ideas, and teamwork, a partnership can reduce the cost of boating while making it into more of a shared activity.

Partnership agreements can be as simple or as complicated as you like. For higher-priced boat, you might want to involve a lawyer. Setting up an LLC can make sense. Even the most amicable agreement benefits from a clear statement of understanding. Situations can and will likely change during the term of the agreement; during change it can be all about the money, so address all aspects. Some basic issues that should be addressed are:

Ownership. List the partners and agree on share of ownership.

Managing Partner. One member will logically take responsibility for paperwork, payment of recurring bills, etc. Discuss how this person is chosen and how the responsibility may be transferred or shared.

Decisions. Describe the decision-making process. Items may be by majority, supermajority, or unanimous consent, depending on the importance and implications of the change.

Title and Insurance. You’ll want full liability and hull insurance. All partners should be named on the title and insurance documents.

Capital Buy-in. This can be as simple as a one-time payment, if the boat was bought with cash. It could involve time payments. If a loan is involved, security must be defined; what happens if the boat is totaled and the settlement plus paid in capital is less than the note?

Division of Expenses. These will be divided according to ownership share, but sometimes division according to usage makes sense. Some costs are fixed; insurance, slip rental, registration, and utilities. Some are predictable; engine maintenance, hauling and bottom paint. Add an allowance for sail replacement, unplanned repairs, and reasonable upgrades. This goes in a kitty, regardless of usage.

Expenses. A boat operational fund may be established to pay for dockage, insurance, maintenance, registration, and all other boat expenses.

True-Up. A partner may get behind on expense or capital payments. How will this be resolved? A true-up upon termination is one possibility.

Level of Maintenance. Agree on the level of maintenance level and how it will be carried out.

If DIY, division of labor should be described. If yard services will be used, it should be clear how expenditures are approved.

Returning the Boat. Set standards for refilling fuel and water and for pumping waste. Be sure to address for cleaning and stowing gear.

Procedures and Checklists. Have a checklist for before departure and after use.

Scheduling. Describe how usage is divided and conflicts will be resolved. This can be a real challenge in-season if the partners work full time.

Storage. Describe where the boat will be stored, whether in a marina or on land. If the boat may be relocated, describe how that is decided.

Dissolution. In the event a partner wants to leave the partnership, describe the options, including selling the boat or a buyout by the remaining partner or partners Typically, the remaining partners have first right of refusal; we set a pre-agreed par value, which could, of course, be negotiated.

Death, divorce, and right of survivorship. What happens if a partner passes away or gets a divorce?

Valuation. Clauses that discus transfer of shares are better defined if a maximum or par valuation for the boat is established.

Sunset Date. An expiration date to the agreement lets things end amicably if something goes wrong. A three to five-year span is typical with a chance at extension.

Dispute Resolution. Describe how disputes might be resolved. The best answer may be to dissolve the partnership.