Sail buying tip #2

Sailmakers around the world have been printing up new business cards even though they continue to work for the same franchised lofts. Their new cards have swapped job description titles from sailmaker to sail designer, a result thats partly due to the proven value of computer-aided design and partly due to a growing trend toward sending sailmaking overseas. Like so many other industries, sailmakers have responded to the lure of lower labor rates and the growth in high-tech manufacturing skills in Asia. Many of the big-name lofts have curtailed much of their domestic sail production and instead focus on building each customer a virtual sail in their local loft, digitizing carefully made measurements, and electronically forwarding the data to a mega loft on the other side of the globe.

Sailmaking success continues to be measured in units of satisfied customers, and despite the remote location of the loft floor, this globalized approach seems to present a viable model, both from the perspective of the consumer and the business. Its true that not as much dialogue can take place between the loft salesman, sailmaker, and skipper - a kind of collaboration that in the past led to some important decision making and genuine brand allegiance. But a capable sail designer can still deliver the goods. To do so, he must address three critical points: capture accurate initial measurements, use sophisticated design software to customize sails for the specific boat, and match the design work with the sailing preference and crew skill level.

Fortunately for those who savor the working relationship that they have had in the past with the favorite salesman/sailmaker, there are still smaller independent lofts where sewing machines continue to whir away and where the sailmaker who built your sails is still willing to join you for a sea trial. Such lofts are like independent hardware stores - an endangered species, something well all certainly miss when the full effect of centralized sailmaking take hold. Some of the independents will survive on the repair work that the sailing season generates, but many see the handwriting on the wall and are turning production over to wholesalers such as China Sails Factory in Guang Dong Province, Southern China.

For more advice and recommendations on sails - what to buy, carry and use - purchase Practical Sailors ebook Sail Buying, Sail Making, & Mainsails.

Also, check out the complete 3 volume series, A Look at Sails at a price that gives you one ebook free when you buy the other two.

Riding turn tip #1

From The Handbook of Sailing

Riding turn

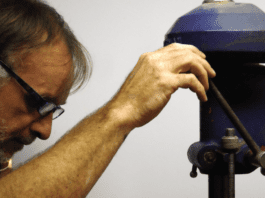

Sometimes, when winching, the coils of sheet on the barrel become crossed (known as a riding turn). This is usually a result of taking too many turns on the winch. It cannot be undone unless the tension is removed. Another line is first tied to the sheet, between the winch and the sheet lead, using a rolling hitch. The new line is then taken around a spare winch and wound in until it is taking the strain from the first winch and the riding turn can then be released. If you find that riding turns are occurring frequently, you should check the angle of then sheets to your winches.

For more hints and tips on sailing techniques for both the beginner and experienced sailor, purchase Bob Bonds The Handbook of Sailing from Practical Sailor.

Heating Systems Article – tip #1

Have you ever stopped and thought about how many boat heating options there are?It can be over-whelming even for the most experienced technical mechanic.And yes, there are a multitude of ways to extend the season and keep a cozy cabin, ranging from simple to complex. But how do you choose the best heating option?You must consider many factors, when making this decision.

A definite correlation exists between the degree to which we are warm and dry, and the enjoyment of a sail, or a night at anchor. A damp and chilly environment may be exacerbated by a poorly insulated hull, leaks, and sweating. Sitting beneath a drippy port or headliner, or curling up in a damp bunk, make or break your sailing experience.

Your boat can be matched to a heating system that, at one end of the spectrum, will simply prevent the formation of icicles or, at the other, provide a space as warm as that den at home. Sources range from electric "cubes" and oil-filled radiators plugged in dockside, to hanging lamps, to the nautical equivalent of central heating. Cost ranges from almost nothing to the limits of your credit card, notwithstanding the recapture of part of the initial cost when the boat is sold.

So how do you decide what heat source to go with?Start with the hidden danger of carbon monoxide poisoning. There are two related dangers in heating a boat with any kind of fossil-based fuel. The first is the chance of producing and/or concentrating carbon monoxide in the living spaces. As we know, CO will kill us straightaway. The second is complacency in assuming that we have the CO angle covered adequately. The more the brain is deprived of oxygen, the less able it is to understand what's happening to it. So, proper ventilation of living spaces aboard a heated boat, no matter what type of system is used, no matter whether it's vented outboard or via portholes and companionway, is absolutely vital.

Whether you are just considering upgrading your heating system or just ready to start the project,start your research and sharpen your technical know-how by reading Nigel Calder's comprehensive guide on how to maintain, and improve your boat's essential systems.If it's on a boat and it has screws, wires or moving parts, it's covered in the Boatowner's Mechanical and Electrical Manual.When you dock or leave the deck with this book, you have at your fingertips the best and most comprehensive advice on technical reference and troubleshooting all aspects of your boat gear.

PS Entry level cruisers – tip #3

Entry-level cruising boats

Excerpted from Practical Sailors ebook, Entry-Level Cruiser-Racers

The C&C 27 followed quickly on the heels of the successful C&C 35. The design is attributed to 1970, with the first boats coming off the line in 1971. The boat evolved through three subsequent editions-the Mark II, III and IV (the latter are hulls #915-#975, according to an owner)-with the latter finishing in 1982. But the hull was essentially the same and not to be confused with the MORC-influenced 27-footer that followed about 1984, with an outboard rudder. That boat lasted until 1987.

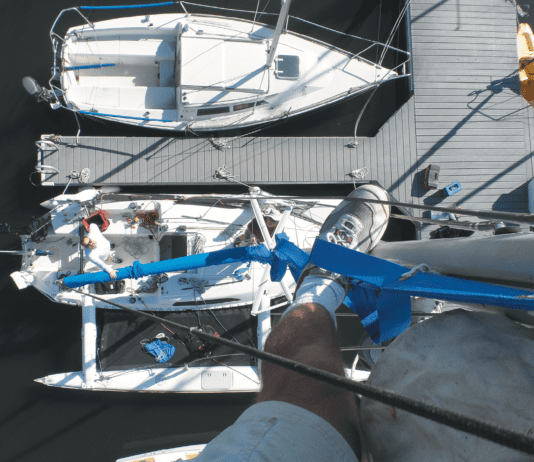

The C&C 27 is a good example of what made the company successful-contemporary good looks with sharp, crisp lines that still appeal today. The sheerline is handsome. Below the waterline, the swept back appendages are dated but thats of little consequence to most owners. In the Mark I version, the partially balanced spade rudder is angled aft, with a good portion of it protruding behind the transom. In one of his reviews for Sailing magazine, designer Robert described the C&C 27s rudder as a scimitar shape that was long in the chord and shallow. In 1974, the rudder was redesigned with a constant chord length and much greater depth and less sweep angle.

The keel, too, was redesigned in 1974 though both are swept aft like an inverted sharks fin. The new keel was given 2-1/2 more depth and the maximum thickness moved forward to delay stalling. Hydrodynamic considerations aside, the worst that can be said of the 27s keel is that it takes extra care in blocking when the boat is hauled and set down on jack stands (or poppets as they are called here in Rhode Island). Without a flat run on the bottom of the keel, the boat wants to rock forward.

The rig is a masthead sloop with a P or mainsail luff length of 28 6 and an E or foot length of 10 6; interestingly, this gives an aspect ratio of .36, nearly identical to the .35 ratio of the Tartan 4100 reviewed last month. In response to the September article on skinny masts with single lower shrouds, the owner of a 1974 model wrote, My 1974 C&C 27 has double lowers with a tree trunk of a mast, which I know will support any headsail in any condition, probably even if I drove the boat full steam into an immovable object. Not so the earliest models.

The owner of a 1977 model wrote to say that the Mark I and II models had shorter rigs and more ballast. The change occurred in 1974, along with several others, some of which weve already noted.

Length overall was first given as 27 4; for later marks it is listed as 27 11. Waterline length started at 22 2, increasing to 22 11. The bow overhang is attractive, but more than is found on most boats nowadays. Remember that waterline length directly affects speed.

Displacement, too, changed over the years, between 5,180 pounds,5,500 pounds and 5,800 pounds. (The owner of hull #54 says that boats before #250 were 1,000 pounds heavier.) Depending on which waterline dimension you use, the displacement/ length ratio (D/L) ranges from 211 to 237. The sail/area displacement ratio (SA/D) is between 17.3 and 19.4. With moderate displacement and a generous sail plan, the C&C 27 is fleet. PHRF ratings for the Mark I average around 200 seconds per mile, dropping to about 190 for the Mark II and 175 for the Mark III.

From the C & C 27 review. To read the complete review of this popular sailboat, in addition to ten other entry-level cruisers, purchase and download the ebook Entry-Level Cruiser-Racers, Volume One from Practical Sailor. For a list of the boats reviewed, and details on Volume One of this series, click here.

Practical Sailor 2015 Index

Annapolis, tip #5

The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Fourth Edition

John Rousmaniere

Page 323

Excerpted from The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Fourth Edition

HANDS ON: Anchoring Hints

Safe anchoring depends as much on cautious, alert seamanship as it does on strong ground tackle. You should have an anchor big enough for your boat (plus some), a nylon rode in good condition that is long and stretchy enough for the anticipated water depth and strains, and sufficient chain to keep the rode low to the bottom. Use all your senses to determine if the hook is holding: bearings on landmarks, the sound of waves splashing dead on the bow and on the sides, the bounce-bounce as her stern rises and falls when shes secure and when shes dragging.

If there are three irreducible rules of thumb for safe anchoring they are: avoid lee shores like the plague; don't anchor too close to other boats; and when in doubt, let out more rode. All too many sailors can tell hair-raising stories about boats dragging down on them and, eventually onto shore in the midst of a midnight thunder squall.

It is land, not the sea, that is a ships greatest enemy, and if you plan to avoid a run-in with land, choose and use your ground tackle wisely.

For additional advice on all aspects of sailing, purchase The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Fourth Edition from Practical Sailor.

The Weekend Navigator, tip #1

Excerpted from The Weekend Navigator, Second Edition, Bob Sweet

Planning as You Go with GPS

Find Where You Are

Its always a good idea to keep a chart by the helm, preferably with your stored waypoints and routes marked on it for easy reference. On all but larger boats, which have space to lay out a chart, youll probably keep the active chart conveniently folded with the active area face up, so you can work with the chart on your lap. Unfortunately, when you do this, the latitude and longitude scales are often hidden from view. The following techniques will help you find your location without using these scales.

Location along an Active Leg

If you are following an active leg of a course or route, determining your position is greatly simplified. You can reasonably assume that you are somewhere along that course line. All you need do to confirm that is to look at your GPS Highway or Map Screen. Then, because stored GPS waypoints are also noted on the chart, even if the route leg itself is not plotted, draw a line from the waypoint you just left to the active waypoint youre headed toward. Now, where are you along that line? Here are some quick tricks to find out:

- Bearing to a Landmark - Simply sight on a charted feature to the side of your current course, usually a landmark or a buoy. It is enough to estimate a relative bearing quickly by eye; then on the chart, align your plotting tool to that relative bearing and move it to intersect the charted feature. See where it intersects your course line? You are there!

- Using a Grid Line - Scan along your active course line. Is there a plotted grid line (a line of latitude or longitude) on the course in front of you? If so, you can do your planning from where that grid line intersects your course line. Now all you need to do is proceed along the course line and watch your GPS display until you reach that precise latitude or longitude. You then know where you are.

- Using a Waypoint - Obviously, if you wait until you reach your current active waypoint, you will know where you are. Alternatively, you can use another waypoint stored in the GPS or a charted object near your course line. This is a variation on the bearing approach, but here you are looking for a nearby object. The easiest and safest way to do this is with a beam bearing to that object. Plan from that spot, and use your skilled mariners eye to identify when you have reached that location. If you are planning to use a stored waypoint that does not represent a buoy or other visible, charted feature, use the Map Screen to eyeball when this waypoint is abeam of your course. The closer the object is to your course line, the more accurate your established position will be.

For more advice on navigating with your GPS and other electronics, purchase The Weekend Navigator from Practical Sailor.

The Weekend Navigator, tip #2

Excerpted from The Weekend Navigator, Second Edition, Bob Sweet

Double-Checking Your Navigation

Quick Comparisons with the GPS

A quick comparison of visual bearings with their corresponding GPS bearings isn't precise, but it will give you confidence in what your GPS is telling you. This very simple technique will encourage you to make regular checks.

Your GPS Map Screen displays nearby landmarks and buoys whose waypoints you have programmed into your unit. You may need to zoom out to bring them into the field of view, and you need to get yourself oriented. Generally you will be using a North-Up display on the GPS, and your direction of travel will be indicated by the orientation of the boat symbol (usually a sharp triangle). If you are sighting quick relative bearings, such as a beam bearing, simply look to see whether the chosen landmark appears to be abeam of the symbol on the screen. If the GPS has truly failed, it is unlikely that the two will agree; if the two agree, it is unlikely that the GPS has failed. If you are still uncertain, take some more precise bearings for comparison.

If youve sighted a bearing across the compass, you need a numeric GPS bearing to compare it with. Using the cursor key on a newer model GPS, scroll to that buoy or landmark on the Map Screen; when it is highlighted, the GPS will show its bearing in a data window. Simply compare the GPS reported bearing with your visual observation. Assuming you set up your GPS to magnetic direction, no conversion is required. If the GPS bearing and your observation match, at least within about three to five degrees, your GPS appears to be working properly.

If any of your quick observations do not match, its a time for a more detailed approach.

For more advice on navigating with your GPS and other electronics, purchase The Weekend Navigator from Practical Sailor.

Offshore Sailing tip #1

Jacklines and Cockpit Pad Eyes

Jacklines are ropes, wire, or webbing stretched between the bow and stern of a boat to which crew clip their safety harnesses when moving about on deck. Offshore, they should be left rigged (attached) in place, regardless of weather.

Jacklines made from flat nylon webbing are generally considered preferable to round wire, which will roll underfoot. The breaking strength requirement is a minimum of 5,000 pounds. The color should be very bright so that they are visible both day and night. The drawback of colored jacklines is that they may bleed their dye on deck. To avoid this mess, soak them in a bucket of water before using.

The design I recommend is a continuous length with a loop sewn in at the bow, which is then shackled to the stemhead. The two aft legs tie off to the stern cleats the same way one would belay a line. With one continuous line, the sewing of the loop at the bow is not terribly critical. If using two separate jacklines, one for each side of the deck, the loop stitching must be protected from chafe with tape.

To read more tips to keep your sailing safer and more enjoyable, purchase Offshore Sailing: 200 Essential Passagemaking Tips from Practical Sailor.

Offshore Sailing tip #2

All-Chain Anchor Rodes

Anchor chain should be secured to the boat so that you don't lose the bitter end overboard. Some people shackle the end to a through-bolted pad eye below decks in the anchor locker, but this can be difficult to undo in an emergency.

It is better to splice a piece of rope to the bitter end of the chain and tie the rope to a pad eye in the chain locker. The rope should be long enough to reach from the pad eye to the deck through the windlass chain pipe. If and when it is necessary to get rid of the anchor rode (generally when another vessel has dragged down on you and has fouled your chain), it is expedient to run the chain to its end and then cut the rope on deck rather crawling into the chain locker and trying to undo a shackle that could be under a lot of pressure.

I also paint the last 20 feet or so of chain with Day-Glo orange paint so I know when Im coming to the end. To mark length on the chain rodes, paint 3-foot lengths every 25 feet or so. Shorter marking are not visible when the chain is whizzing out.

To read more tips to keep your sailing safer and more enjoyable, purchase Offshore Sailing: 200 Essential Passagemaking Tips from Practical Sailor.