Offshore Sailing tip #3

Marking Sails

A few minutes with a waterproof marker can save a lot of time when you are changing sails on a dark and stormy night. For hanked-on sails, I draw an arrow pointing up at each hank. For boats with furling sails or boats equipped with racing luff extrusions such as Tuff Luff, I mark the luff tape on the sail with an arrow at about 2-foot intervals. Write Head, Tack, and Clew on each sail in the appropriate corner. On the head and tack, identify the sail itself - like 130 percent Yankee.

To read more tips to keep your sailing safer and more enjoyable, purchase Offshore Sailing: 200 Essential Passagemaking Tips from Practical Sailor.

Tidal Stream – Tip #1

The effect of a tidal stream is a significant factor when navigating on any point of sailing, but can be crucial when sailing to windward. If you are in a small boat sailing to windward against a strong tide, it can often prevent you making any headway at all and it may be best to enter a port or anchor until the tide or wind changes direction. If this is not possible, you should try to keep to shallow water, away from the strongest stream. The presence of a strong tide will also affect the strength and direction of the apparent wind. When the boat is beating against the tide, the apparent wind speed will be reduced because the boat is being carried downwind. The converse also applies. When the tide is running across the wind on the lee bow, advantage can be gained because it increases the speed of the apparent wind and alters its direction so that the boat is effectively freed and can point higher. When the tide is on the windward bow, the effect is the reverse, so try and tack when the tide changes to keep it on the lee bow.

For more hints and tips on sailing techniques for both the beginner and experienced sailor, purchase Bob Bond's The Handbook of Sailing today!

The Essential Knot Book for Boats tip #1

Excerpted from: The Essential Knot Book for Boats, Fourth Edition

Handling Ropes and Lines

Not surprisingly, some consideration has to be given to the handling and care of all these high tech ropes.

Do:

- Keep them coiled or hanked neatly to prevent tangling

- Run them out carefully to avoid kinking and knotting.

- Coil laid ropes in clockwise loops (for right-hand lay) and use figures of eight for braids.

- Wash out salt, sand, grit and mud, which will otherwise chafe and destroy the fibers.

- Try to hang coiled or hanked ropes in a locker rather than dump them in an untidy heap.

- Protect all lines from chafe.

- Use eye splices rather than knotted loops for permanent or high load attachments.

- Use blocks whose sheaves have diameters in the ratio of at least 5:1 with that of the ropes they will carry.

- Ensure the rope fits comfortably into the groove of the sheave its passing round.

- Seal and whip ropes ends. Braided sheaths in particular fray very quickly.

Dont:

- Leave high tech lines exposed to high levels of ultraviolet light for long periods of time.

- Kink or twist any type of rope.

- Dont stand or walk on ropes and lines.

- Surge lines, particulary polypropylese ones, too fast around winches or cleats or theyll melt.

- Use rope stoppers that are likely to crush the rope's core; some of the more exotic materials are prone to damage of this nature.

To learn more about the proper care of lines along with simple instructions and clear photos for tying the most useful knots for your boat, purchase The Essential Knot Book for Boats, Fourth Edition from Practical Sailor.

The Annapolis Book of Seamanship tip #2

Tips for Safer Sailing

Be forehanded. Here are two definitions. 1) The rule of 6 Ps: Proper prior preparation prevents piss-poor results. 2) Youre preparing for the voyage you may have, not the one you want to have.

Keep a lookout. Sailors in close touch with their surroundings are safe sailors. In crowded waters or near land, a conscientious lookout should always be assigned.

One hand for yourself, one for the boat. Watch out for your personal safety while attending to the boats and your shipmates. If you see someone behaving unsafely, say something.

Be aware of your environment. This advice from the great English circumnavigator Chay Blyth means sailors must keep a wide-ranging weather eye.

Every boat needs a captain. When leadership is obscure, tight situations get even tighter, says Karen Prioleau, and experienced captain from Southern California. Commands must be correct, clear, and decisive.

Have an organized crew. Crew selection was the key to our success, said the captain of a boat that did well in the Newport Bermuda Race, Dale McIvor. Get lots of experienced crew who know how to enjoy themselves and keep things light. With that tone having been set, there were no clashing egos, or bad moods. And, he added, Find a good cook.

For additional advice on all aspects of sailing, purchase The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Fourth Edition from Practical Sailor.

Sailing a Serious Ocean tip #3

Heavy Weather Myths Debunked

Before getting into fitting-out for heavy weather and preparing for storms before they arrive, lets debunk a few common myths. First, the notion that with todays excellent satellite-weather forecasting, you can essentially avoid heavy weather. This sanguine notion is the voice of inexperience. If you plan to sail across oceans and cruise the world, you will encounter heavy weather. Think about how accurate local forecasts are in your hometown. Now add the vagaries of the ocean environment and the uncertainties of changing climate to the mix and you can pretty well count on encountering some unexpected storms in your travels. The Azores approach storm of 2007 was not forecast and caught much of the Atlantic crossing fleet by surprise.

The second myth is that you can outrun heavy weather if your boat is fast enough. While there is some truth to the notion that you can limit your exposure to storms by taking aggressive steps to sail out of harms way, particularly if you know the path of the storm, generally this is not viable for most cruising boats traveling at 6 to 7 knots. Time is better spent preparing for the ensuing blow. I do have to admit, though, that I have never understood why boats lying in the predicted track of a tropical storm don't move out of the storms way rather than assuming the bunker mentality and hunkering down for the blow. If you are at anchor in Antigua, in the Leeward Islands of the Caribbean, and a hurricane is a couple of days away and tracking west, why not make all haste south to Grenada or, better yet, Trinidad? Its 300 or 400 miles due south, and in two days you can be completely out of storms swath of destruction. Todays tropical storm track models are very accurate, at least in the big picture, so the choice of where to sail is usually very clear. I think this is a better strategy than doubling and tripling your mooring lines and offering prayers and bribes to every available deity in hopes that the storm will change course.

The 2012 tragic loss of the replica tall ship Bounty in Hurricane Sandy points to flaws in both strategies mentioned above. If there ever was a time for hunkering down, this was it, as Sandy spread terror across the Atlantic like a malignant tumor. While I understand the skippers angst about having the storm surge damage his ship in port, the potential for losing the ship and the crew by taking what in reality was a movie prop to sea in hurricane conditions was a terrible combination of arrogance and negligence. Captain Robin Wallbridge and crewmember Claudine Christian paid for this mistake with their lives, and only heroic actions from the Coast Guard prevented more loss than life.

There was no way the Bounty was in a position to outmaneuver Sandy, but whats difficult to understand is why she didnt at least try. With the storm tracking northwest toward the New Jersey shore, the Bounty cleared out of New London, Connecticut, and, after rounding Montauk Point on the east end of Long Island, laid a course right toward the approaching storm. No attempt was made to outflank the storm by sailing east. Nobody knows for sure why Wallbridge sailed back toward the coast and ultimately collided with the storm off Cape Hatteras.

John Kretschmer has logged more than 300,000 offshore sailing miles and his new book, Sailing a Serious Ocean is filled with not only stories of his voyages but sailing tips and advice, no sailor should be without. To purchase Sailing a Serious Ocean, go to Practical Sailors website now.

The Annapolis Book of Seamanship Tip #1

Excerpted from The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Fourth Edition

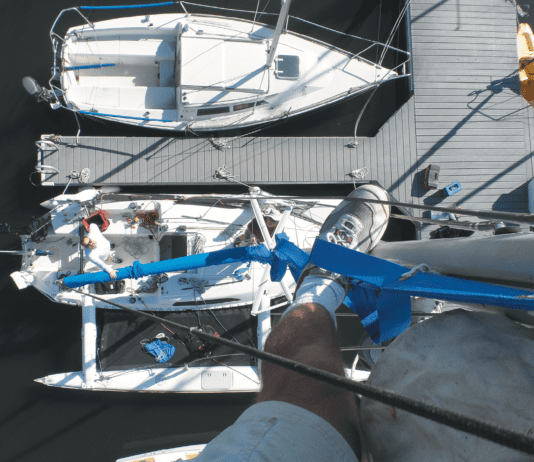

HANDS ON: Near a Pier

A large proportion of accidents around boats take place at the dock. Always respect the power of a moving boat, her gear, and her surroundings. Keep hands, feet, and other parts of your body clear of the boat, trailer, and float. Once under way remember that the boat can't be steered unless she is moving, so don't go too slowly. But also be aware of the tremendous potential force of a moving object weighing thousands of pounds. With practice, youll be able to predict how the boat will steer at various speeds.

When handling docking lines that are under load, relieve some of the force by snubbing them, or taking a turn or two around a cleat or winch.

In tidal areas, be aware of tidal currents. A current of only 1 knot may seem slow, but every minute it carries a boat 100 feet.

Be aware of the winds strength and angle. A sailboats tall rig is especially sensitive to the wind, which will push the boat ahead, astern, or to the side depending on its direction.

For additional advice on all aspects of sailing, purchase The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Fourth Edition from Practical Sailor.

Sailing A Serious Ocean tip # 2

Excerpt from Sailing A Serious Ocean - by John Kretschmer

Ric and Diane were on watch as we approached the northern edge of the Gulf Stream. Daylight was just creeping above the horizon. Within minutes the conditions changed from moderately rough to extremely rough. Ric, although relatively inexperienced as a helmsman, especially in heavy weather, was doing a fine job of steering Quetzal down the face of steep and occasionally breaking seas. Diane was sitting in the cockpit, facing aft and watching Ric and the huge waves piling up astern. Both were harnessed to the boat. They were cold and tired but seemed strangely satisfied and looking forward to the end of their watch in less than an hour. Ric and Diane has been making plans to buy a cruising boat, ditch their land lives, and take up full-time cruising. They had signed aboard for this exact moment, to get a taste of heavy weather and lean how to cope with a cruel sea.

The ride had become noticeably different, and even from below I knew that Quetzal was in a danger zone. I was anxious to get on deck. I slid the companionway back and felt the rush of warm air, a signature of the Gulf Stream. I slammed the hatch behind me and stepped into the cockpit.

I heard the wave before I saw it. It crested with a deep-throated roar. I ratcheted my head up and saw the monster curling above the stern. It occupied most of my field of vision - it was the largest wave I had ever seen. It was a moment of complete clarity, and time slowed as the wave began to break. I knew we were going to be crushed, and I wondered, coldly, objectively, if we would survive. I instinctively clutched the support rail on the side of the companionway and shouted, Hold on.

A torrent of salt water swallowed us in frothy rush. The bimini and solar panel frame crashed on Ric, flattening him behind the wheel. Quetzal didnt go over, didnt broach. Somehow she regained her footing, straightened up, then dug her deep keel into the kissing foam and refused to budge.

I was stunned and enormously relieved to see Diane. She was right where shed been before the wave hit. What force, what power, what magic had held her in place? She looked at me with an expression that Ill never forget. She was bewildered but not afraid, as if she knew shed experienced something that would frame the rest of her life. Ric was also okay, although he was unable to move, pinned down by debris. He even managed a smile. I briefly wondered how the crew below had fared.

But time was not standing still; it just seemed that way. Queztal was wallowing. Another wave broke across her beam and flowed through the cockpit. It was not a massive wave but it didnt matter. It swept Diane away.

I watched in horror and stunned disbelief as the wave carried her aft. I leaped after her. She was already most of the way off the boat, when the backs of her legs snagged the upper lifeline. A split second later I had a death grip on her thighs. I tried to drag her back into the boat, but I couldnt overcome the force of the water. Ric, who had to watch this appalling spectacle helplessly, reached out for her as he desperately tried to free himself.

I screamed at Diane. Get back in this boat. Youre not going anywhere.

But I didnt believe it. Pulling with all my strength, I tried to lift her back aboard. But I failed. My world was crashing. For nearly a decade, Quetzal and I had carried new sailors across calm and calamitous seas. But now the future was suspended by a lifeline and a couple of shackles, a particle of time. I knew that if Diane was washed away, I was going with her, and it would all be over.

Once again it seemed like time stopped. Even today I can close my eyes and see Diane peering out from her hood pulled tight around her face. I can hear myself screaming at her and at the ocean.

But Diane would turn out to be the lucky one that day, as you will find out in Chapter 10.

John Kretschmer has logged more than 300,000 offshore sailing miles and his new book, Sailing a Serious Ocean is filled with not only stories of his voyages but sailing tips and advice, no sailor should be without. To purchase Sailing a Serious Ocean, go to Practical Sailors website now.

Sailing a Serious Ocean tip #1

Standing Watch

As you probably suspect already, and will certainly know if you continue reading this book, I am not a skipper who blindly adheres to the hard-and-fast rules of the sea. In fact, for the most part I abhor them because successfully handling a small boat in a large ocean requires a flexible attitude and the wherewithal to change tactics as conditions dictate. You must assess the situation and take preemptive action, and if that doesn't work then try something else. Thats how serious sailors cope with challenging weather and equipment failures. Following rigid rules can be more dangerous than helpful. I must confess, however, that I am a tyrant when it comes to standing your watch, and all my nice guy sensitivity vanishes if you don't show up on time.

When the watch system breaks down, everyone loses their rhythm, and, more importantly, they lose off-watch rest time and vital hours of sleep. Fatigue is a stealthy enemy at sea. This heartless attitude toward watchstanding is geared mostly toward larger crews, four or more, and I am a little tolerant of watch adjustments with small crews. Sometimes you are feeling strong and connected to the wheel (or at least the autopilot controls) as the boat hurtles before the wind, and the mermaids are flirting with you, and the stars are telling you stories, and you just don't want to end your watch. Thats a different situation. Some nights you know that your partner really needs sleep, and extending your watch is the right thing to do. Remember that you have to replenish the hours of missed sleep; they add up like unpaid credit card bills and almost always results in a happier passage.

Back to my sensitive ways. I feel strongly that watchkeeping should apply only to the evening hours. This book looks at bluewater sailing as an incredibly fulfilling way to live, as a preferred way to spend your precious time, and standing watch day and night can suddenly feel like youre punching a clock on an assembly line. There has to be time for whimsy and thought at sea, and theres no better environment on the planet for unfettered thinking than a boat at sea, and this should not be shoehorned into a navel system of discipline and around-the-clock watches. I believe all of this deeply. But just the same, don't be late for your evening watch.

John Kretschmer has logged more than 300,000 offshore sailing miles and his new book, Sailing a Serious Ocean is filled with not only stories of his voyages but sailing tips and advice, no sailor should be without. To purchase Sailing a Serious Ocean, go to Practical Sailors website now.

Seamanship Secrets #4

Secrets of the Most Accurate LOP on Earth

When the two charted objects line up as viewed from your boat - say a church spire behind a tank - you have a range (also known as a transit). A range provides a flawless line of position (LOP). When planning a cruise, look ahead, behind, and to the sides of your track for pairs of charted objects that will line up as you proceed. Natural ranges help you stay on track, show your boat's speed of advance, and strengthen the quality of any position fix. You can use any combination of landform tangents, landmarks, beacons, and buoys as a range. You needn't convert a bearing to true or magnetic or even use a protractor. Just draw a line on the chart through the two objects, extend the line over the water, and you're somewhere on that LOP. No error, no slipped parallel rulers, no fuss, and no doubt about it. Cross that LOP with a bearing to an object off the beam, and you've got a solid fix. Here are some ways to use ranges:

Track drift: Keep in a channel by choosing two objects that are in line and dead ahead of your course. But check dead astern, too. Over-the-shoulder ranges give the quickest warning that your boat is drifting off track.

Track advance: The elapsed time between successive ranges along the side of a trackline will enable you to calculate your boat's speed over ground, or advance, along the trackline.

Track turns: Use a natural range to tell you when to turn onto a new trackline. Plot this range onto the trackline ahead of time. Label the line TB for turn bearing.

Fast and easy line of position (LOP): When two charted objects line up, write down your time and draw the LOP over your trackline. This gives you an instant estimated position (EP). Upgrade it to a fix by taking and plotting a bearing to a charted object 60 to 120 degrees off the range.

How To Regain A Range After Drifting

Range ahead: If you start drifting off a range dead ahead, follow the direction of the closer object. If the closer object is to the left of the more distant object, turn left; if it is the right, turn right.

Range astern: (over-the-shoulder): if you start to drift while using an over-the-shoulder range, follow the direction of the farther object. If the more distant object is to the left, turn left; if to the right, turn right.

For 185 tips and techniques that you won't find in any textbook, but will work quickly and reliably every time, buy Seamanship Secrets, 185 Tips & Techniques for Better Navigation, Cruise Planning, and Boat Handling Under Power or Sail from Practical Sailor.

Seamanship Secrets tip #3

How to Correct for Leeway Wind Drift

All vessels tend to sideslip, or make leeway, except with the wind dead ahead or astern. High-freeboard power vessels make leeway at slower speeds when the wind strikes their sides. Sailing vessels make lots of leeway when hard on the wind and less leeway when well off the wind. Light airs and heavy winds have more impact than moderate breezes.

Three Methods For Estimating Leeway

Choose any of these methods to make a rough estimate of your boats leeway angle.

1. Take a bearing on your wake trail. Use your handbearing compass to estimate leeway angle. Sight dead astern with your compass. Wait several minutes, then sight along the wake line to windward. The difference in the two angles gives you your leeway angle.

2. Take a bearing to an object astern. Find a landmark, light structure, or buoy dead astern. Take a bearing with the handbearing compass. Hold a steady course for several minutes, and then take a second bearing. The difference in bearings is your leeway angle.

3. Leeway by backstay wake angle. Steady up on a course for a few minutes until you see a wake trail to windward. Swing the boat quickly, lining up the backstay with the wake trail. Glance at the compass heading. The difference between the two headings is your leeway angle.

Steering Upwind To Correct For Leeway Angle

To correct for leeway, be sure to apply correction to your steering course in the proper direction. You want to steer the boat closer to the wind to counteract the effect of leeway. If the wind blows from the port side, subtract the angle from your course. If the wind blows from the starboard side, add the leeway angle to the course.

For example, you are close-reaching on the starboard tack, steering a course of 350 degrees magnetic. You sight astern with the handbearing compass for a reading of 170 degrees magnetic. Five minutes later, you sight down the wake line, and the bearing is 164 degrees magnetic. The difference gives you a leeway angle of 6 degrees. Youll need to point 6 degrees higher, so add the angle to your 350-degree course and steer a new course 356 degrees magnetic.

For 185 tips and techniques that you wont find in any textbook, but will work quickly and reliably every time, buy Seamanship Secrets, 185 Tips & Techniques for Better Navigation, Cruise Planning, and Boat Handling Under Power or Sail from Practical Sailor.