Seamanship Secrets tip #2

How to Sail Home if the Steering Fails

My little ODay Javelin, at 13 feet, skimmed across the blue-green waters of Biscayne Bay. Picture perfect it was, with puffy cumulus cotton balls pitched here and there across the blue sky over the Atlantic. After a couple of hours of sailing, I was getting a bit bored and decided it was time to teach myself something new.

I leaned over the transom and released the rudder pintles that were seated in the transom gudgeons, and hauled the rudder aboard. Now I was rudderless. For a terrifying moment I felt hapless. Id just neutered my boat and was holding its main underwater appendage in my bloody hands! Id recently read about practicing sailing without a rudder, but could it be done? Sure enough, I was able to beat, tack, and reach by alternately tensioning or easing the jib and main.

This is a valuable skill to practice, and while my little javelin had a tiller, many sailboat wheels operate the rudder through a complex system of quadrant gears and cabling. If a wire snaps, a skipper needs an alternate steering method. Of course, you do have that oddball emergency tiller crammed in one of those sail lockers, don't you? But have you tried it out? You may need to remove the wheel from the steering pedestal to get enough room to move the emergency tiller from side to side. Test this at the dock and underway.

With a bit of practice, you can steer, turn, tack, and jibe a boat with just her sails. In a small boat, make steering under sail more effective by shifting crew weight forward or aft. This raises one end of the boat higher than the other. The wind will blow against the higher end, moving the low end in the opposite direction. Follow these easy-to-learn steps:

1. How to sail in a straight line. Practice straight-line steering first. Sail onto a close-hauled or close-reaching course. Lock the wheel or lash the tiller amidships. Line up the forestay or bow pulpit on two distant objects. Try to stay lined up on your natural range.

Heading up. Trim the mainsheet and ease the jib or genoa sheet. Move the crew forward to lower the bow and raise the stern.

Falling off. Trim the jib or genoa and ease the mainsheet. Move the crew aft to lower the stern and raise the bow.

2. How to fall off the wind

Sail Trim. Ease the main and keep the headsail sheeted in. If needed, backwind the headsail to push the bow to leeward. If the boat refuses to fall off, reef the main or change to a larger headsail.

Crew position. Move the crew aft.

3. How to head up toward the wind

Sail trim. Sheet in the main and ease the headsail.

Crew position. Move the crew forward.

4. How to tack

Sail trim. Sheet in the main and ease the headsail. When almost into the wind, pull on the windward headsail sheet to backwind the jib and help turn the bow through the wind.

Crew position. Move the crew forward. After tacking, move the crew aft.

5. How to jibe

Sail trim. Turn the boat off the wind as described above (see step 2). With good momentum, you should be able to pass the stern through the wind. Just before the jibe, sheet the main flat amidships and let the headsail fly free. Quickly ease the main immediately after the jibe to prevent your boat from rounding up to windward.

Crew position. Move the crew aft.

For 185 tips and techniques that you wont find in any textbook, but will work quickly and reliably every time, buy Seamanship Secrets, 185 Tips & Techniques for Better Navigation, Cruise Planning, and Boat Handling Under Power or Sail from Practical Sailor.

Inspecting the Aging Sailboat tip #1

Excerpted from Don Caseys Inspecting the Aging Sailboat

There arent many experiences more ripe with promise than buying a boat. When you find the very craft you have been dreaming about sulking impatiently on a cradle or shifting restlessly in a slip, perfect days on the water suddenly play through your mind. You step aboard and run your fingers over her in a lovers caress. Look how perfect she is. This is the one! You stand at the helm, gripping the wheel, feeling the wind through your hair, the sun on your back, the motion of …

SNAP OUT OF IT!

Are those cracks in the gelcoat? Should the deck crackle like that? Are those rivets in the rubrail, and why are they loose? Why doesn't the head door close? Why are there brown streaks beneath the portlights? Are those water marks inside the galley cabinets? Should there be rust on the keel bolts? What is that bulge in the hull?

If any of these indicate real trouble (and some of them do), it is about to become your trouble. It is going to be your money paying for the repair or, God forbid, your feet treading water. So be still your beating heart; shopping for a boat is about looking for warts.

But where do you look? And what do you look for? And when you find something, how do you know what it means? Thats what this book is all about.

Interior

The interior of a boat is a trap. Manufacturers discovered long ago that attractive interiors sell boats. If you don't believe it, go to a boat show and compare the amount of time shoppers spend below to the time they spend on deck. Nice woodwork and plush upholstery are essential to getting signatures on the dotted line.

There is nothing wrong with having a great-looking interior - but never use interior dcor to judge a boat. Far too many manufacturers building to a budget have scrimped elsewhere to put money into their boats interiors. This strategy is often successful financially, but intellectually - and perhaps morally - it is bankrupt. Coordinated colors and rubbed varnish don't account for much when the wind pipes up and the seas start to crest.

Dont misunderstand; a cozy woody interior is a definite plus over a boat with the interior charm of a refrigerator, but you should not be overly influenced by a boats below-deck look. Treat a fab interior as a bonus or as a tie-breaker, but not as a major selection criteria.

Whats behind the wood and fabric is what youre most interested in. Is the deck hardware through-bolted with generous backing plates? Are all through-hull fittings accessible? Are electrical wires secure or are they free to chafe dangerously against raw glass as the boat pitches and rolls? A couple of sheets of veneered plywood can hide a plethora of flaws and omissions. Make sure both the intent and the function of the interior design is nothing more sinister than to give the boat added appeal.

Cabinets and furniture can also seriously complicate some emergencies. Imagine sailing into submerged debris; if the hull was holed below the waterline, could you get to the damaged area to stem the flow from inside?

Look at the cabin of a boat critically. Fight the tendency to form an opinion based on a pleasing dcor. Interior varnish and velvet have almost exactly the same significance as a nice shade of red engine paint; they don't give a reliable indication of anything.

Don Caseys book, Inspecting the Aging Sailboat will show you, step by step, how to evaluate the condition of an older fiberglass sailboat - the one you own or the one youd like to purchase. To buy a copy of Inspecting the Aging Sailboat from Practical Sailor, click here.

Seamanship Secrets tip #1

Fuel-Fire Prevention Techniques

Marine firefighters estimate that you have less than 30 seconds to get a fire on any boat under control. Many items on your boat burn extremely hot, including fiberglass. It takes no time for liquids like gasoline, propane, or kerosene to reach flash point and give off combustible vapor. At that point, one spark causes combustion. (Diesel fuel has a relatively higher flashpoint, but it is still a flammable liquid that must be handled with care.)

On vessels, most serious fires start during fueling or cooking. Fuel fires almost always are the result of improper pre-fueling and post-fueling procedures. Galley fires combine improper preheating, storage, vapor ventilation, and failure to monitor cooking activities.

A basic checklist goes a long way in preventing common emergencies. Make it simple and keep it in a three-ring binder. Laminate the lists, or put them into document protectors, and separate the lists with tabbed inserts.

Below are the tools and steps required for safely fueling your boat.

1. Run blowers for 5 minutes to rid bilges of vapors. Close hatches, opening ports, vents (including dorados), and doors. On sailboats, insert dropboards into the companionway opening and close sliding hatch.

2. Keep a fire extinguisher ready for immediate use. Remove one of the portable extinguishers from its bracket. Lay it on deck, on its side, to keep it from rolling around.

3. Place diapers or absorbent pads over downhill scuppers and drains. This prevents fuel form spilling from the deck and into the cockpit and overboard.

4. Assign one crewmember to watch the fuel gauge. V-shaped fuel tanks cause gauge readings to be somewhat erratic. The gauge rises quickly when you start fueling, and then slows to a crawl near the tank top.

5. Place a rag around the nozzle or fuel fill hole. Insert the nozzle and maintain contact with the fill to prevent buildup of static electricity. When you are three-quarters full, assign a crewmember to monitor the fuel vent. Have him or her hold an absorbent pad or diaper under the vent in case of overflow. Top off each tank to 90% to allow for expansion.

6. Replace the nozzle and wipe up any spills. Check the cap gasket for cracks and proper seating. A cracked or worn gasket leads to water intrusion into the fuel tank. Replace and tighten down the fill cap. Check all around the boats waterline for fuel spills. Cleanup any spill immediately with absorb pads. Do not - under any circumstances - use a dispersant. (This is a U.S. federal law.)

7. Open all vents, hatches, opening ports, and doors. Run the blowers for 5 minutes. Tour the vessel and snip for vapor fumes. If you smell fuel, locate the source before you start the engine. After starting the engine, check the waterline again for spills - paying particular attention to the area beneath each fuel vent. Check the engine compartment for fuel leaks.

For 185 tips and techniques that you wont find in any textbook, but will work quickly and reliably every time, buy Seamanship Secrets, 185 Tips & Techniques for Better Navigation, Cruise Planning, and Boat Handling Under Power or Sail from Practical Sailor.

Inspecting the Aging Sailboat tip #3

Excerpted from Don Casey's Inspecting the Aging Sailboat

DELAMINATION

Delamination in fiberglass is the functional equivalent of rot in a wooden boat. Well-constructed solid-fiberglass hulls (meaning not cored) almost never delaminate unless they have suffered impact damage or unless water has penetrated the gelcoat. This is because proper hull-construction technique - adding each layer before the previous one has cured - results in the resin linking chemically into a solid mass. Occasionally a manufacturer defeats this by leaving an uncompleted hull in the mold over a weekend; but most know - and do - better.

Introduce core into the formula and the likelihood of delamination increases dramatically. A core divides the hull in three distinct layers - the outer skin, the core, and the inner skin - with the bond between them strictly mechanical. Polyester resin adheres chemically to itself with amazing tenacity, but it has never been very good at adhering to other materials. At the slightest provocation it will release its grip on the core material, regardless of what it is.

PERCUSSION TESTING

Tapping a fiberglass hull is akin to spiking a wooden one. Use a plastic mallet or the handle of a screwdriver to give the hull a light rap. If the laminate is healthy, you will get a sharp report. If it is delaminated, the sound will be a dull thud. Your hull is sure to play more than two notes, but map all suspect returns; then check inside the hull to see if a bulkhead, tank, or bag of sails is responsible. If not, it is the laminate.

It is essential to do a thorough evaluation of a cored hull because core delamination is unfortunately common and robs the hull of much of its designed strength. Tap every 2 or 3 inches over the entire surface of the hull. Be especially suspicious of the area around through-hull fittings and near signs of skin damage or repair. Percussion testing can also reveal filler patches.

Don Casey's book, Inspecting the Aging Sailboat will show you, step by step, how to evaluate the condition of an older fiberglass sailboat - the one you own or the one you'd like to purchase. To buy a copy of Inspecting the Aging Sailboat from Practical Sailor, click here.

Inspecting the Aging Sailboat tip #2

Excerpted from Don Caseys Inspecting the Aging Sailboat

SIGNS OF STRESS OR TRAUMA

Fiberglass generally reveals stress problems with cracks in the gelcoat. The cracks can be very fine and hard to see; get close to the hull and lay your finger against the spot you are examining to ensure that your eyes focus properly. A dye penetrant such as Spot Check (available from auto-parts suppliers) can highlight hairline cracks.

Dont confuse stress cracks with surface crazing; crazing is a random pattern of cracks - something like the tapped shell of a boiled egg just before you peel it - that occurs over large areas of the boat. Stress cracks are localized and generally have an identifiable pattern to the discerning eye.

IMPACT DAMAGE

A collision serious enough to damage the hull usually leaves a scar, but sometimes the only visible record of the event is a pattern of concentric cracks in the gelcoat. Impact with a sharp object, like the corner of a dock, leaves a bulls-eye pattern. Impact with a flat object, like a piling or a seawall, tends to put the stressed area in parenthesis. Tap the hull with a plastic mallet or a screwdriver handle in the area of the impact and listen for any dull-sounding areas, which indicate delamination. Examine the hull inside for signs that the impact fractured the glass.

PANTING

Panting occurs when poorly supported sections of the hull flex as the boat drives through the waves. This problem is also called oilcanning, taking its name from the domed bottom you push in and let spring back on a small oilcan. Panting usually occurs in relatively flat areas of the hull near the bow, but it may also occur in flat bilge areas and unreinforced quarters. The classic sign is a series of near-parallel cracks, sometimes crescent shaped, in the gelcoat. If you can move any portion of the hull by pushing on it, the hull lacks adequate stiffness. Left unchecked, panting can result in fatigue damage to the laminate and eventually a hinge crack all the way through the hull.

For more advice on ways to identify signs of stress or trauma in a sailboat, purchase Don Caseys book, Inspecting the Aging Sailboat. To buy a copy of Inspecting the Aging Sailboat from Practical Sailor, click here.

Riggers Apprentice tip #3

Excerpted from The Complete Riggers Apprentice

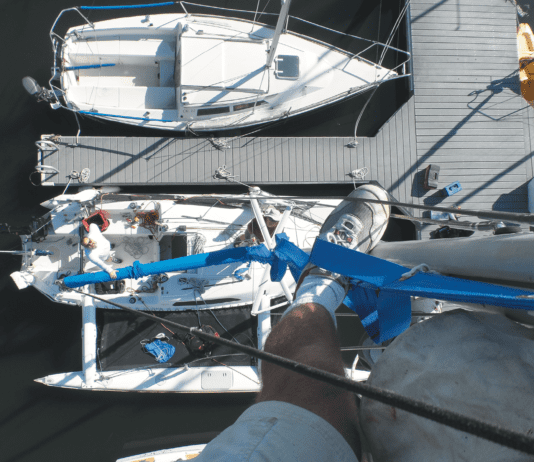

Mast Steps

Mast steps are a popular way to get aloft, as easy as climbing a ladder, as the sales literature says. But did you ever try to climb a wet, cold, awkwardly shaped ladder that was waving back and forth in the air? For all but flat-calm conditions, mast steps are no treat, and even in flat calm you need to have a safety line attached to you and tended on deck.

It makes much more sense to have an efficient bosuns chair routine set up, one that enables you to go up in any conditions and to stay up there without having to hand onto a ladder. And without the weight, windage, and expense.

But there is one place - about 4 feet down from the masthead - where mast steps are a really good idea. Just a pair of them at this height gives you a place to stand when you need to get at the very top of the mast, higher than a halyard can take you. Of course, you want to be sure youre tied to the mast before you do this, so theres no danger of pitching out of your chair.

To read all you need to know about modern and traditional rigging, purchase The Complete Riggers Apprentice from Practical Sailor.

How to read a nautical chart tip #1

Fundamental Chart-Making Concepts

Until recently, there has been little need for chart users to understand the technology of chart-making, particularly its limitations, because the tools used by navigators to determine the position of their vessels were inherently less accurate than those used to conduct and display the surveys on which charts are based. Realizing the limits of accuracy of their tools, navigators tended to be a cautious crowd, giving hazards a wide berth and typically taking proactive measures to build in an extra margin of safety for errors and unforeseen events.

Knowing this, and knowing that navigation in inshore waters was by reference to landmasses and not astronomical fixes, surveyors were more concerned with depicting an accurate relationship of soundings and hydrographic features relative to the local landmass (coastline) than they were with absolute accuracy relative to latitude and longitude. The surveyors maxim was that it is much more important to determine an accurate least depth over a shoal or danger than to determine its geographical position with certainty. Similarly, the cartographer, when showing an area containing many dangers (such as a rocky outcrop), paid more attention to bringing the area to the attention of the navigator, so it could be avoided by a good margin, than to accurately showing every individual rock in its correct position.

All this changed with the advent of satellite-based navigation systems - notably the global positioning system (GPS). Now a boats position (latitude and longitude) can be fixed with near-pinpoint accuracy and, in the case of electronic navigation, accurately displayed on a chart in real time. This encourages many navigators (myself included) to cut corners more closely than they would have done in the past. With such an attitude, it is essential for the navigator to grasp both the accuracy with which a fix can be plotted (whether manually or electronically) and the limit of accuracy of the chart itself - together they determine the extent to which it is possible to cut corners in safety.

To help understand and use electronic and paper charts, purchase Nigel Calders How to Read a Nautical Chart from Practical Sailor.

How to Sail Around the World Tip #1

Excerpted from How to Sail Around the World

Cruising under sail is a hundredfold more complex than merely buying a suitable yacht. We know this because the marinas and harbors of the world are dotted with private pleasure craft, most of which go nowhere at all. There are tens of thousands of boat owners but very few sailors. Pay attention to this phrase: lots of boat owners but very few sailors. And a sailor you must be if youre going to try ocean voyaging. You need a modicum of sailing aptitude, some ability to fix things, and the willingness to pitch in and work.

Most veteran long-distance small-boat sailors are free spirits who fall into the classification of restless adventurer and who are always looking at distant horizons and trying new things. These spooky engineers usually lack fancy certificates, but theyve all served fairly intensive apprenticeships and have learned a good bit about the sea, the care of their vessels, and the management of themselves.

To learn the fundamentals of sailing, you need to go to a special school for a few weeks. You will be taken out in a dinghy or small vessel for instruction in sail handling, tacking, gybing, docking, maneuvering in restricted waters, and following safety procedures. Then you must practice as often as possible and serve as crew for friends on their yachts.

In the beginning, you will only be a grunt, but little by little it will come to you. Every time you sail on a different vessel, you learn a thing or two because each captain has his own way of doing things. You need to practice stitching sails, to find out about anchors and rigging, and to get some notion of sanding and painting and fixing things because life under sail is a never-ending round of maintenance, modifications, and large and small repairs.

For more cruising lessons, advice and stories, purchase Hal Roths How to Sail Around the World from Practical Sailor.

How to Sail Around the World Tip #2

Excerpted from How to Sail Around the World

When searching for a boat to buy, you need to answer a few questions. One is What size boat can you handle?

The larger the yacht, the more skill and muscle you need to deal with her. She may have bigger winches, but they will be harder to crank. Hoisting or furling a 500 to 600-square-foot mainsail on a 50-footer is easy to joke about in a yacht brokers office, but can be a surprising handful for you to deal with in a breeze at night. Just because a yacht has a powerful engine, doesn't mean she will be easy to manage in a windy docking station.

I think all experienced world cruisers will agree that learning how to enter and leave tight spots under sail is a skill you should have in your pocket. Unfortunately this is completely alien to present-day U.S. marina type sailing, in which a person motors out from a dock, puts up the sails, goes out for a few hours, and does the same routine in the opposite order when she returns.

You may scoff at this, but if youre in distant waters and there are problems (engine not working, a line around the propeller, dead batteries), you will be very glad to know how to work yourself in and out of restricted waters.

Suppose you want to take fuel and water from a dock against which a fresh breeze is blowing. Do you know how to drop an anchor when youre going into the dock so that you can pull yourself off when youre ready to leave? If youre anchored near a rocky shore and the wind shifts and begins to blow toward the land, do you know how to sail out the anchor without winding up on the rocks? These techniques are not hard to master, but its smart to practice them regularly. It may be useful to learn these maneuvers in a small sailboat and then work up in size because of the considerable weight and the restricted turning ability of a bigger boat. Mistakes are unthinkable and can cost thousands of dollars.

Don't consider close-order maneuvering under sail a troublesome thing to learn. Its challenging and great fun to sail in and out of tight corners. Half the time its just a matter of turning the yacht to head downwind, paying attention to any tidal stream or river current, carefully checking for traffic, and hoisting a jib. Then you let go off the stern lines or haul up a stern anchor, and youre away. Once you have a little sea room, you can hoist the mainsail.

The other half of the time, it requires more study, care, and practice. One person must be in absolute control. You need to figure out exactly what youre going to do, have every bit of your gear ready, and have an alternate plan if possible, and carefully explain whats in your head to each person involved. Often you need to use lines to warp the vessel around to another dock or turn her so that the wind is more suitable. Again, you must check the tidal stream and current if theyre factors.

A way of practicing these maneuvers without embarrassment is to go to a safe, shallow, deserted anchorage. Drop a fender on a light anchor for a mark and use it as a practice target for sailing out the anchor and other procedures.

For more cruising lessons, advice and stories, purchase Hal Roths How to Sail Around the World from Practical Sailor.

How to Sail Around the World Tip #3

Excerpted from How to Sail Around the World by Hal Roth.

A basic problem with sailing vessels is chafe - things rubbing against one another to destruction - and I refer to it again and again in this book. If a piece of line rubs against a sharp metal corner, theres a good chance that the line will be ruined or cut in two in a few hours. But if protected by a piece of hose or by better routing, perhaps by a way of a smooth block, a line will last for years. Veteran sailors are always looking at their rigs when under sail to check three things:

- the trim of each sail and the whole rig together

- whether the sails are suitable for the current wind strength

- whats rubbing on what

To suggest what can be done, I made two circumnavigations with the same main halyard on my 50-footer. (I end-for-ended the -inch diameter line after 30,000 miles to put a new section around the masthead sheave.) But Ive also ruined new lines in a few hours because I got sloppy and inattentive.

For more cruising lessons, advice and stories, purchase Hal Roths How to Sail Around the World from Practical Sailor.