Photo courtesy of Ralph Naranjo

375

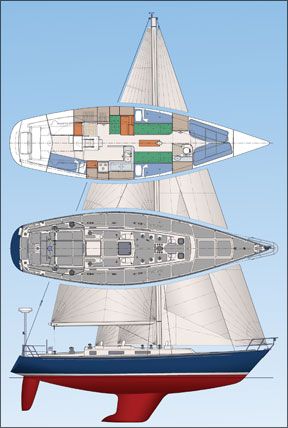

You won’t find the U.S. Naval Academy’s new sail training sloop, the Navy 44 MkII at any yacht brokerage, but a close look at the boat helps put today’s crop of racer-cruisers into proper perspective. The Navy 44 is meant to be cruised and raced for 20 years, and to endure two or three times the wear and tear of the average production sailboat. In short, it is a cut above the competition, particularly in terms of structural integrity. Features such as the color palette of the fabrics, the appeal of an aft cabin’s “island berth,” and the location of the entertainment center were completely off the designers’ radar screen. The Navy’s new sloop is a utilitarian yacht that’s workboat tough and raceboat efficient.

Design

The journey to design consensus on the Navy 44 MkII project was circuitous, at times seemingly navigated by bureaucrats in a rowing shell with no coxswain to guide them. But finally, after years of difficult collaboration and input from a wide range of key players (Navy Sailing, midshipmen, USNA Naval Architecture Department, Naval Station Annapolis, the Fales Committee, NAVSEA, Combatant Craft Division, and others), a contract was awarded to Pearson Yachts.

Designer of record David Pedrick created the boat under very specific design criteria. The goal was to maintain what had worked well aboard the Navy 44 Mark I, modernize the hull shape, sailplan, and foils, and add innovation where appropriate. The original Navy 44 was created by McCurdy and Rhodes in the mid-1980s and built by Tillitson and Pearson. During the course of 20 years of rigorous use, the boat had proven to be a durable, reliable all-around capable sailboat. In fact, the Mark I had done such a commendable job, that there was some talk of simply duplicating the design. But after years of mission statement development and design review, a Navy captain handed down the rudder order: “We don’t build the same destroyer over again, and we’re not going to build the same sailboat either!”

So Pedrick set out to design a new sloop retaining many of the proven attributes of the original boat. He widened and flattened the canoe body, modernized the foils, but kept the massive, heavily reinforced keel-to-hull joint. Some might call this overkill, but when you’re designing a sailboat that will see three times more use than a charter boat and still be capable of two decades’ worth of offshore racing without a major refit, the stakes are high. Add to this the need to endure jibes, groundings, knockdowns, and the press of overzealous, well-meaning but inexperienced crews, and the implication of “safety margin” takes on a whole new perspective.

Sure, there are faster and prettier boats around, but the U.S. Naval Academy prefers a rugged vessel that can deliver decades of “heavy-duty” usage. Keeping the scan’tlings a significant cut above the prevailing recreational sailboat fleet is the way the Navy 44 MkI lasted so long, and the MkII approach would be the same.

During the design phase of the project, Ralph Naranjo (now PS technical editor) coordinated USNA’s role in the design process. One of the toughest challenges was balancing the often conflicting requirements of a sailboat that would act as sail-training platform for all midshipmen and also be a race boat for more experienced crews.

The biggest challenge, however, lay in achieving the requisite strength, stability, and longevity while keeping weight from overwhelming performance.

USNA Naval Architecture Professor Dr. Paul Miller, who is also a competitive sailor, enlisted several students to carry out relevant research. One midshipman’s research into composite construction showed that chop strand mat and polyester resin lay-ups endured a fraction of what stitched and woven laminates with high-fiber contents could endure. He also confirmed that well-executed sandwich structures with low void content provided excellent stiffness as well as strength, but in regions where high loads were focused, such as in the garboard region, chainplate area, and at the location of the lower rudder bearing, solid fiberglass reinforced plastic (FRP) laminate made the most sense.

Photo courtesy of Ralph Naranjo

288

The appendages on the new boat were changed considerably in order to add better steering characteristics and to provide foils with increased lift.

ON DECK

The dual-purpose nature of the new boat made it more of a racetrack-friendly station wagon, rather than a dockside second home. By no means are these boats “cruisers” if big berths, biminis, and arm chairs define the genre. These sloops are set up to be sailed by a full crew and intentionally laid out to insure that the midshipmen are kept busy with plenty of sailhandling. In fact, the deck layout might leave the impression that the Navy owns stock in sailboat hardware companies.

There are six hefty, two-speed 48s just aft of the spar, and the cockpit coamings are dominated by two powerful Lewmar 77s. Two more sizable secondary winches ride on the aft end of the house, and two 48s for mainsail trimming are located next to the traveler.

The reason for this apparent winch overkill is twofold: The first is that the novice sailors get plenty of opportunity to handle a loaded line, and there’s no need to fumble with a rope clutch during an 0300 “all hands” response to a squall. Secondly, tasks such as reefing are expedited by having separate winches and crewmembers to handle the sheet, halyards, and reefing line. The fact that the boat is usually sailed with a crew of 10 means that there are plenty of hands available, and tools to work with. The maintenance history of the MkI boats showed that oversizing winches and other hardware improved reliability and also added to longevity.

Mechanical and Electrical

The Yanmar 4JH4E naturally aspirated diesel is meant to provide propulsion in a calm, not deliver thrust to power into headwinds and steep seas. Its modest smooth-running 56-horsepower block sits in a secure box at the base of the companionway steps and provides “all around” easy access to pumps and dual alternator setup. Output from the 100-amp ship’s system alternator, and the stand-alone 55-amp starting battery alternator can be shared in case either fail. Battery banks (AGM) can be paralleled, and all of the vessel’s electrical and electronic systems are energized via breakers on a control panel near the nav-station.

All of the new sloops, like the ships of the gray Navy, are quite well electronically equipped. In addition to a full array of B&G electronics, Furuno radar, GPS, and NavNet digital chart system, there’s an Icom VHF and SSB. There’s even room at the chart table for a laptop, and though no built-in satellite communication system has been installed, it’s easy to add an Iridium or other LEO portable terminal. That’s what has been done aboard the Bermuda-bound Mark I boats for the past few years. The new Navy is all about technology, and gauge watching, for better or worse, has to some extent replaced the role of the seaman’s eye.

Accommodations

Spartan minimalism lies at the heart of this boat’s interior design theme. Stepping below, there’s no sense of wasted taxpayer money, but underway essentials—a good berth, functional galley, head, and a very handy wet locker—are quite user-friendly. In fact, one distinguished, retired three-star admiral once said that the older Mark 1 boats “held all the ambience of an abandoned shack.” The new boats are bright and shiny but still have not strayed far from the commitment to form and function.

Photo courtesy of Ralph Naranjo

288

On opposite sides of the companionway are the galley (starboard) and a wet locker and nav-station (port). The main saloon space is occupied by upper and lower berths, and just forward of the mast is a head compartment with a hanging locker to port. The forepeak has a foursome of pipe berths that will house sails more often than crewmembers. While underway, the crew “hot racks,” using the four berths in the main saloon and a quarter berth aft. All berths come with adjustable tackle and lee cloths, and are designed for effective use on any tack.

The galley offers a nicely gimballed, three-burner Force 10 propane stove and oven, along with a large, well-insulated ice box/refrigeration system. There’s ample counter and locker space and a double sink along with a stout stainless-steel tubular rail that gives the cook a de facto U-shaped galley.

Good lighting, fans, and hatch placement add to the functionality of these sailboats. But in the world of boat-show “wow factor,” the subtle effect of usable sea berths, six dorade vents, handholds galore, superb nonskid, and heavy-duty construction might go unnoticed.

In fact, some of the most functional attributes of the boat would draw gasps rather than awe from brokers and many of their potential clients. Take, for example, the overhead (actually the real underside of the deck), which is studded with hundreds of big washers and machine screws capped with acorn nuts. It’s an honest testimony to how well the hardware is attached, and how well the structure is reinforced. There’s been no effort to hide the fasteners, and leaks developing down the road will be easy to find and fix—not the case when all is hidden behind an overlay of vinyl, foam and staples.

Performance

This sailboat is neither a house afloat nor a fragile, anorexic race boat. It’s an ocean passage maker with enough performance to turn in a good showing en route to Bermuda or in coastal competition. (In June’s Newport-Bermuda Race, Defiance, a Navy 44 MkII, finished 4th in its 15-boat class.) It is tough enough to handle a couple of decades’ worth of offshore sailing and can cope with light air and gale-force conditions.

With a deep draft and full sections aft, the boat provides much more windward sailing capability than what’s found aboard cruising boats of a similar size. Its finishes in local regattas will of course be subject to the whim of the rule of the moment, but its healthy seaworthy design will make it a fine Bermuda racer.

288

Designed as a masthead sloop with a removable inner forestay, the new 44 carries a basic sail inventory of a mainsail, genoas 1-4, spinnaker, storm jib, and storm trysail.

Many wonder about the use of conventional piston-hanking headsails, but with a full crew of agile midshipmen, it’s good to give them something to do. In addition, each sail is cut for a specific wind range, and the piston-hank’s fail-safe construction and easy repair at sea are pluses. Head foils can easily be added, and race crews can use luff-tape genoas if desired.

One of the first differences PS testers noticed while sailing the new boat is the finger-tip light feel of the spade-rudder steering. The design of the new, ruggedly built, carbon-fiber rudder yields a much more efficient lifting surface than the MkI’s rudder/skeg combination. And when added to the boat’s higher initial stability and reluctance to heel in the puffs, handling characteristics went from good to excellent.

While beating in 20 knots of wind, we sailed with a single reef and a No. 3 genoa, a sail combination that provided good balance and control. The mainsail trimmer works just forward of the helm while genoa trimmers have plenty of room to crank the big Lewmars. The secondary winches mounted on the cabin house separate those trimming the spinnaker, a sensible arrangement aboard a vessel designed with a priority for underway operation rather than at anchor or in-port luxury. Missing was the pounding of a modern race boat’s ultra flat underbody, a feature that appeals less and less during an ocean passage.

Neither lightweight nor rigged with a large fractional sail plan, the MkII is a functional throwback to masthead rig versatility. A removable inner forestay and running backstays offer an ideal means for setting a storm jib, and adding a reaching staysail when desired. The use of a symmetrical masthead spinnaker and full-hoist genoas make sense, especially with the Chesapeake Bay’s reputation for light air.

Like all sailboats, the new “44” is a compromise of attributes, but when it comes to seaworthiness and rugged construction, the line holds true. Interestingly, all it would take are a few creature comfort modifications below, some sailhandling simplification on deck, and this sail training workhorse could become a performance cruiser’s thoroughbred.