Oceans may interconnect the planet, but they also act as a barrier, isolating the sailors on opposite shores. Some cruisers and racers bridge the gap, while most keep track of international sailing events and incidents online. Well-run international regattas, around-the-world yacht races, and the globalization of the boatbuilding industry help to spread the word, but-despite such publicity-not all sailing trends reach the opposite shore. Thats why the crew at Practical Sailor does its best to note whats trending. Usually, its a new boat design or piece of hardware that draws our attention, but in this article, we focus on a seafaring controversy: the growing inclination toward renting adventure.

The new trend offers amateur sailors the chance to purchase a crew slot aboard a powerful, ocean-racing sailboat. Its like a skippered bareboat junket in the British Virgin Islands turning into a Mount Everest expedition. But in this iteration, there are fewer Sherpa pros and much more reliance on a paying, rather than paid, crew. The result is a fine line between marketing sailing adventure charters and selling slots in an extreme sport encounter.

The first iteration of the around-the-world Clipper Race was more of the former rather than the later. Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, a cofounder of the first Clipper Race and later chairman of Clipper Ventures, has been instrumental in the races evolution and its subsequent uptick in vessel design and the nature of the challenge. The original 1996 event was run using eight Clipper 60s designed by David Pedrick. These masthead cutters more closely resembled the venerable Camper Nicholson cruiser/racers and sail-training vessels of the era. In 2000, a new fleet of Dubois-designed, 68-foot cutters was built to add more performance potential to the mix. Finally, a third, 75-foot Clipper cutter was designed by Tony Castro, and any hint of a cruising boat seemed sidelined in favor of a proven ocean-racer pedigree.

The routes to be sailed were more demanding downwind legs, and when the 68s came online, there were reliable reports of surfing speeds approaching 30 knots. The masthead in the Pedrick 60 was 75 feet above the water, and now the spar in the Clipper 70 is 95 feet tall. As the boats have become much more turbo-charged, requirements for the crew have remained being that no previous sailing experience necessary…. a good fitness level, over 18 and a thirst for adventure, as the Clipper website (www.clipperaroundtheworld.com) explains.

Until this past year, the safety record had been good, and questions about crew competency and the seats-for-sale approach to sailing adventure had remained muted. But when Andrew Ashman, 49, aboard IchorCoal, was hit by the mainsheet tackle and killed in 2015, lingering questions began to rise about skill level and the pay-to-play, big-boat oceanic racing format. Several months later, Sarah Young, 40, another crewmember aboard IchorCoal, tragically perished in a crew-overboard incident. Two deaths on the same vessel, in the same race, tipped the scale, and while the European press featured summaries, analysis, and memorial tributes, the commentary in the U.S. sailing press has been pretty scan’t.

The reason that Practical Sailor is wading into the fray is the universal importance of individual risk awareness. By understanding where we are on our own risk/reward scale, we can make better decisions about whether or not to reef, carry on, or head for safe shelter. But when big names in sailing offer the ultimate adventure and promotional dollars gild the package, theres a feeling that one can skip the apprenticeship in big boat, offshore racing, and simply pick the skills up along the way.

Theres nothing new about events based on the idea that if their check clears, youre on the team. Whether its a sailing regatta, mountaineering experience, helicopter powder skiing, or other high risk/high reward activity. However, most organizers weigh participant skill level, and it plays into determining how to safely deliver the desired outcome. Most want to see more in a prospective customers resume than their fitness level and commitment to a quest for adventure.

Its true that to be completely safe under sail means that the dock lines will remained fastened more often than not. But the flipside of this safety/risky coin may mean that one must be willing to count on good luck and faith in others to pave the way through the tougher challenges. The more experienced and capable the crew, the less luck one needs. But the need for luck returns when theres only an experienced skipper aboard an unforgiving, 75-foot ocean racer, and he must also run a sailing school afloat-all while power-reaching through some of the worlds most challenging seas.

The U.S. yachting press does a great job of being an upbeat, cheerleader for the industry. We agree that sailing is something to lavish with enthusiasm, but the best way to do it is to be realistic about the challenges and to keep reminding readers about what happens when they are caught unaware of a impending consequence.

In June 2016, during a race from New Zealand to Fiji, the mainsheet failed aboard the Ron Holland, 65-foot sloop Platino. The flailing boom hit and killed boatbuilder Nick Saull. In the ensuing chaos, another crewmember was swept overboard and lost at sea. A couple of months earlier, the crew of Clipper Round the World Yacht Race boat LMAX temporarily stopped racing to check on and lend assistance to the dismasted sloop Sayo. A crewmember from the Clipper 70 volunteered to swim to the apparently abandoned vessel and found the skipper deceased below decks. Authorities were advised of the situation, and the Clipper crew provided position details. A month later, Sayo was rediscovered near the Philippines and taken in tow.

Its unlikely that Ashman or Young assumed that perishing at sea was a plausible outcome to their Clipper Cup adventure. Only those aboard IchorCoal really know what happened in each incident, so rather than playing Monday-morning quarterback, we assembled a small team of experts to look into the inherent risks involved in ocean sailing. The team included an ex-fighter pilot, a naval architect, and PS Technical Editor Ralph Naranjo, an author and well-known player in the safety-at-sea lecturing circuit.

PS Risk-management Panel

Charlie Pooch Pucciariello was an All-American dinghy racer at the U.S. Naval Academy (USNA), and later, while on active duty, he earned the distinction of being the Navys top F-14 pilot in the Pacific Fleet. He and his wife, Nona, raced and cruised a Corsair 31 trimaran and recently powered up with a new, 37-foot Corsair. Their sailing is seldom in the slow lane, and Pucciariello has merged a lot of pilot training and dinghy sailing know-how into a blend of forethought and on-the-fly multihull decisionmaking.

Dr. Paul Miller, a naval architecture professor at USNA, is a composite structures specialist who has worked on several Americas Cup campaigns. He and his wife, Dawn, merged interests in dinghy racing and traditional wooden boats. They have raced and cruised their classic Herreshoff 28-foot Rozinante on both coasts and have learned just how hard they can push an older wooden boat. Miller believes that every skipper needs to understand the design and structural assets and limitations of his/her sailboat.

Naranjo emphasizes that together, crew skill and decision-making make up the most significant leg of a safety triangle concept that he developed for his new book, The Art of Seamanship. He stresses that whether its a 30-minute severe thunderstorm or a three-day storm at sea, staying in sync with weather forecasts, sail changes, and boat-handling tactics are paramount.

Perspective

Pucciariello has swapped his F-14 for an Airbus and become a commercial airline pilot with smooth rides and soft landings replacing top-gun maneuvers. His second career introduced him to whats euphemistically known as the Swiss cheese safety analogy. Its an internationally recognized theory and a part of Cockpit Resource Management for pilots. The cheese theory looks at accident prevention in the context of a stack of sliced Swiss cheese. Each slice has randomly located holes, and these holes represent a shortfall that can lead to a failure. When slices are stacked, theres a good chance that the holes are covered by other slices. In the case of sailing, we could label each slice of cheese with names such as design, engineering, manufacture, maintenance, crew skill, decision-making, safety gear, etc. The premise is that only when a hole is contiguous with other holes, and a tunnel extends from one side of the stack to the other, will an accident occur.

For example, when a man overboard incident occurs, it may initially seem that the victim simply tripped or lost their balance and fell over the side. But closer scrutiny, using the Swiss cheese model, may reveal that there were additional factors involved in the incident. It could be too little sidedeck width, excess camber, inadequate nonskid, or a lack of handholds. It might have been a situation in which the helmsman or another crewmember saw the approaching swell and failed to call out wave. In other words, accidents are often described by the result rather than their contributory factors. Fell overboard and hit by the boom are in the forefront of serious or fatal sailboat accidents. But the name for the incident is an oversimplification.

Its the contributory factors that really need to be scrutinized. Theres often a domino effect in play. It may be either a series of omissions, commissions, or a combination of both that leads to the incident. In some cases, it may be as simple as the right piece of hardware mounted incorrectly that puts the crew at risk. Or it may be a design flaw that affects boat stability. For example, a vessel may have lots of initial stability derived from a wide beam, but such righting moment disappears quickly as heel increases. If theres not enough ballast or the boats center of gravity is not deep enough, a knockdown becomes much more likely. And along with this comes a reluctance to recover from extreme angles of heel. (See Dissecting the Art of Staying Upright in the June 2015 issue online for an in-depth discussion on boat stability.) Stability and strength are two key assets of an offshore racer or cruiser, and the implications of vessel design and material specifications show up in slices of our nautical Swiss Cheese-the fewer and smaller the holes, the better.

When it comes to a cruising or boat-delivery context, a crew has more incentive to shorten sail, dial back the loads, and improve the boats behavior in a seaway. Reefing early and knowing when its time to switch to storm sails lessen the torment that both the crew and the boat must endure. When racing, however, everyone wants to win, but in order to make that happen, you can’t afford to break the boat. Knowing how hard a vessel can be driven is one of Millers favorite topics.

The tragic loss of Cheeki Rafiki is a case in point. In communications with their shoreside base, the crew revealed that for days before the vessel foundered, they had been pounding into a building seaway. There were concerns about noises emanating from the hull and an increase of water entering the bilge-all signs of significant structural concern. Its not known whether the crew slowed down to lessen the load on the garboard, deeply reduce sail, or switch to storm sails. We will never know whether the critical failure was due to an initial design flaw, construction-linked issues, or the result of prior damage and repairs, but the net result was that Cheeki Rafiki failed in a catastrophic fashion with the keel shearing from the hull. (See A Quest for Keel Integrity in the May 2016 issue online and Cheeki Rafiki Loss Puts Spotlight on Keels-Again in the May 27, 2014 blog post online.)

The incident apparently unfolded so quickly that the crew was unable to make use of the life raft or other survival equipment. Safety equipment is a vital slice of Swiss cheese, but in the full tempest of a mature storm at sea, a crews best friend is vessel integrity and the prospect of staying afloat and right side up. These are reasons why Miller points out that not alone do sailors need to know the as designed specs and as built reality, but they need to know the current condition of the vessel and how time and usage have affected the structure.

Learning from the Past

A vessels appropriateness for a specific type of service begins with a design statement that expands into a spec and finally a set of line drawings and engineering details. Some boats are shoal-draft, lightly built, inshore cruisers while others are designed to cope with and endure the onslaught of high winds and big seas. You can take the Cape Horn scan’tling sailboat down the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW), but it will do that job poorly compared to the shoal draft, more lightly built cruiser.

Reversing the challenge is another story. Heavy-weather encounters with fleets of recreational sailboats tell their own tale. The 1979 Fastnet Race, the Queens Birthday Storm of 1994, and the 1998 Sydney Hobart Race codified what breaks when conditions reach storm force and seas impart unanticipated loads on hulls and decks. In these incidents, boats rolled, ports and large windows were broken, and deck-to-cabin structures were sheared. Today, ISO Cat A approval does not mean safe in any storm; theres a range of heavy weather that should be labeled as untenable.

The boat design and construction process is part of risk mitigation, and the process is a balancing act that involves handling competing constraints. A look at the modern race boats reveals a flat bottom, planing hull with a wedge-shaped deck and a wide, shallow cockpit. There are few handholds, and when hiking on the high side, there can be a long fall to leeward. In a seaway, breaking waves have swept crewmembers overboard, prompting more use of harnesses, tethers, and jacklines. Mitigating a design shortfall through the addition of safety gear and crew training is a legitimate response, and it can be graphically portrayed in the Swiss cheese analogy.

In the case of the El Faro sinking and loss of 33 mariners, the most overwhelming factor was the decision to intentionally steam directly into the approaching storm. Had the vessel not lost propulsion, perhaps it would have weathered the maelstrom. But as is often the case, operator error played the key role. In the background, there remain questions about training and organizational oversight and the masters disregard of available forecast data. Once the review process and litigation concludes, hopefully, all of the lessons learned will be made public.

Conclusion

Around the world, there have been fewer news-grabbing tales of sailors aboard sailboats lost at sea. In 2007, the crew of Flying Colours sailed into the very worst part of an early season tropical storm. In extremis, in Gulf Stream waters east of Cape Hatteras, they set off their EPIRB, and after an exhaustive U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Navy search, no trace of the 54-foot sloop or the four-person crew was ever detected. Like many other missing-at-sea stories, such encounters offer us few answers, but we do know what the conditions were like, and they seem to mimic those in which other offshore-capable sailboats have come to grief. The winds were 60 knots sustained and the significant wave height was 30 feet, the vessel was in the vicinity of the north wall of the Gulfstream, and no trace of Flying Colours and her four person crew was left behind.

After considerable research into sailboat accidents, we had to conclude that operator error was more often than not the major contributor. In most cases, there was a lack of awareness of what could-and did-unfold, rather than an intentional charge into harms way. One area of concern was in what Reason terms Pre-condition, the column in which we grouped major structural factors. This included design and construction shortfalls that could lead to loss of an essential part of the boat like the rudder, a chain plate, the mast step, rig, or keel. Obviously, the latter, like any major hole below the waterline, will usually result in capsize and flooding, and ranks right up there with an out of control fire as an abandon-ship incident. So whether you are guided by the Swiss cheese model or plain-old commonsense seamanship awareness, develop a rational understanding of the structural integrity of your boat and keep in mind that operator error is usually a key player when things go wrong.

[Editor’s note: The United Kingdom’s Marine Investigative Branch accident report on the deaths aboard Ichorcoal, produced after this article was published, is available here.]

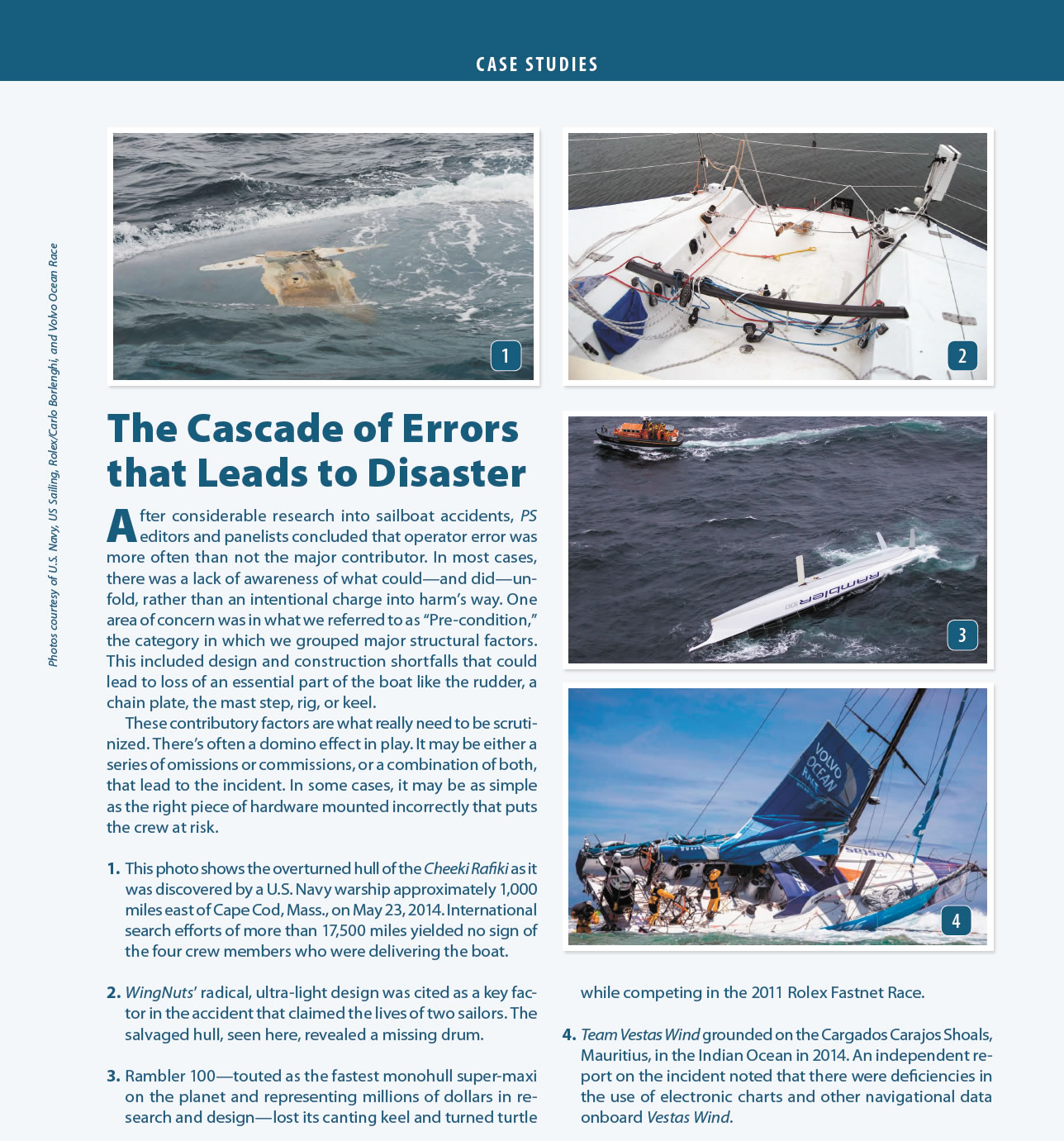

After considerable research into sailboat accidents, PS editors and panelists concluded that operator error was more often than not the major contributor. In most cases, there was a lack of awareness of what couldand didunfold, rather than an intentional charge into harm’s way. One area of concern was in what we referred to as “Pre-condition,” the category in which we grouped major structural factors. This included design and construction shortfalls that could lead to loss of an essential part of the boat like the rudder, a chain plate, the mast step, rig, or keel.

These contributory factors are what really need to be scrutinized. There’s often a domino effect in play. It may be either a series of omissions or commissions, or a combination of both, that lead to the incident. In some cases, it may be as simple as the right piece of hardware mounted incorrectly that puts the crew at risk.

1. This photo shows the overturned hull of the Cheeki Rafiki as it was discovered by a U.S. Navy warship approximately 1,000 miles east of Cape Cod, Mass., on May 23, 2014. International search efforts of more than 17,500 miles yielded no sign of the four crew members who were delivering the boat.

2. WingNuts’ radical, ultra-light design was cited as a key factor in the accident that claimed the lives of two sailors. The salvaged hull, seen here, revealed a missing drum.

3. Rambler 100touted as the fastest monohull super-maxi on the planet and representing millions of dollars in research and designlost its can’ting keel and turned turtle while competing in the 2011 Rolex Fastnet Race.

4. Team Vestas Wind grounded on the Cargados Carajos Shoals, Mauritius, in the Indian Ocean in 2014. An independent report on the incident noted that there were deficiencies in the use of electronic charts and other navigational data onboard Vestas Wind.