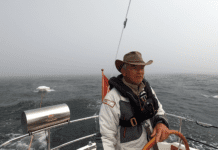

The year 2002 has been a bad year for man-overboard incidents aboard racing sailboats. In May, professional sailor Jamie Boeckel was lost off the foredeck of Blue Yankee during a sail change. On the Newport-Bermuda Race in June, four sailors went overboard from three yachts during sailhandling maneuvers. Miraculously, all four were recovered, thanks in part due to increasing safety awareness after Boeckel’s death.

But a disturbing series of threads link all these incidents. And in all cases, there are lessons to be learned here forthe cruiser as well as the racer.

Stay with the Boat

If you’re attached to the boat, it’s hard to be lost overboard. This is so self-evident as to be ludicrous. As best we can determine, none of the sailors who went overboard during the Bermuda Race was attached to the boat. Wearing a harness does absolutely no good if you are not hooked on.

There’s a lot of pressure aboard serious racing boats to execute sail changes in the least possible amount of time. There is absolutely no doubt that stopping to hook onto a jackline before going forward slows you down. For a professional, being slow on the job is a good way to regain amateur status.

Putting the performance of the boat ahead of personal safety, however, is a false ordering of priorities. Because professional crews spend a lot more time on the job than typical amateur sailors, they’re almost always more comfortable on the foredeck in rough conditions than even the best of amateurs. When something goes seriously wrong, however, the professional can find himself in just as much trouble as the greenest amateur.

Jacklines

The obvious way to stay attached to the boat is to wear a harness, and to make sure you are hooked onto something strong enough to take the strain if you suddenly find yourself at the end of your tether.

Offshore racing regulations require jacklines running the length of the boat, giving an unobstructed route from bow to stern without unclipping your tether. These jacklines are almost always made of flat webbing. The advantage of webbing is that lies flat on the deck, and will not roll underfoot when you step on it. However, there are also some significant caveats when using webbing.

Webbing should be polyester, not nylon or polypropylene. It should have a minimum breaking strength of 6,000 pounds, and should have heavily stitched eyes at either end.

You obviously must have strong points for attachment on the boat at either end. On Calypso, we secure the forward end of the jacklines to one of our big bow cleats. At the aft end, the jacklines are attached to a strong padeye.

The jacklines must be somewhat shorter than the length between points of attachment to allow for a tensioning device. In our case, we use a four turns of quarter-inch Spectra line to make up a purchase at one end. This purchase should be adjusted to keep a lot of tension on the jacklines at all times.

When wet, webbing jacklines stretch dramatically. We cannot over-stress how important it is to keep jacklines tight to minimize the distance you will fall before fetching up.

The jacklines should be light in color to make them easier to see at night. Dark blue is a bad choice in color.

When you arrive in port, remove the jacklines, wash them in fresh water, dry them thoroughly, and put them away out of the sunlight to minimize ultraviolet deterioration. Examine the stitching and webbing periodically to make sure that there are no chafed areas or broken stitches. Replace the jacklines when they show any signs of wear or deterioration. They’re relatively cheap.

Any sailmaker can whip up jacklines for you, or you can buy them ready-made from some chandleries and mail-order catalogs. Don’t guess on length. Measure your boat before buying.

Strong Points

While the jacklines offer good security when moving fore and aft, you should really clip to a fixed strong point when you’re in a single location for an extended time, such as working on the bow or steering. Aboard Calypso, we have three heavy fixed padeyes in the cockpit as attachment points. On most boats, you will also find strong points near the mast and at the bow, such as heavy halyard bails or bow cleats. These must be truly strong points of attachment, capable of withstanding severe shock loads.

You should be able to clip onto one of these strong points, or onto the jacklines, from the security of the companionway. Other than when working on the foredeck, you are most vulnerable to going overboard when coming on deck.

Never, repeat never, attach yourself to your boat’s lifelines. They simply cannot be trusted. Welded bails on stanchion bases, however, can be suitable strong points.

Tethers

How do you transfer your point of attachment from jacklines to a strong point without unhooking? The answer is the dual-length tether. Double tethers consist of a long (six-foot) tether and a short (three-foot) tether, both attached to a single point at the harness. The long tether allows you the freedom to move around deck, while the short tether ties you securely in place if you’re working at the mast or bow. We strongly recommend that the longer tether be of the elastic type to make it less likely to tangle. The shorter tether can be non-elastic. In any case, the tether must be attached to the harness via a snap shackle with lanyard, just in case it becomes necessary to detach yourself in an emergency, for example, if the boat were sinking beneath you.

At the boat-end of the tether, safety hooks such as the Gibb snaphook or Wichard safety hook are the best choices, since they are almost impossible to release accidentally, unlike conventional snap hooks.

Safety regulations for offshore racing now require snap shackles at the harness end of all tethers. Double tethers are required for at least 30% of the crew. For a cruising boat, every tether should be of this type.

Harnesses

The development of inflatable PFDs has revolutionized safety harness design. We believe that the integrated safety harness and inflatable PFD is the only type of harness suited for offshore racing or cruising. Ideally, your harness should keep you aboard, or at least alongside, your boat. But even with the best harness, there are potential weak points: jacklines, strong points, shackles—any could fail, even in the most carefully designed system. If you suddenly find yourself in the water, an inflatable PFD could spell the difference between life and death.

You can buy combination PFD harnesses through US Sailing (the national governing body of the sport), from safety equipment specialist retailers, through catalogs, or at chandlers in every boating area. There are a variety of inflatable PFDs, with and without harnesses, which may make the choice confusing. West Marine, for example, sells virtually identical harness/inflatables under both their house brand and the SOSpenders brand, featuring either manual or automatic inflation.

We have, for the last 25,000 miles, worn the manual inflatable vest with harness sold by West Marine, now designated model 38MHAR.

Manual Versus Automatic Inflation

While the decision to wear a combination safety harness/inflatable PFD is a no-brainer, the choice between manual and automatic (water-activated) inflation is not so straightforward. Historically, automatic inflation has been problematic. The water-soluble bobbins that activate most inflatable vests can work a little too well, and it’s not uncommon for automatic vests to inflate at inopportune times.

The bow of the Swan 51 Temptress, our boat in the Newport-Bermuda Race this year, was frequently under water in the rough conditions of the Gulf Stream. During one headsail change, bowman Tod Yankee’s inflatable vest/harness combination self-activated when he was briefly immersed. On another boat, the automatic vests of four crewmen seated on the weather rail activated when a wave broke over them.

An inflated vest practically immobilizes your head and upper body, making it very difficult to work on the foredeck or at the mast. This awkwardness in itself can pose a danger.

Once a vest inflates in a non-emergency situation, it’s functionally useless until you have the chance to repack it. This is not a job to be undertaken in the middle of an ocean race. You can easily deflate the vest and repack it so that you still have a usable harness, giving you a least half a functioning safety system.

The Hammar inflation system used in the high-end Millenium vests sold by West Marine promises to eliminate accidental activation, since it uses a hydrostatic activation system similar to those used in commercial-grade life rafts. These inflatables should not self-deploy under the normal conditions of wetness, but it is not clear whether a real dunking on the bow of a boat would be enough to trip the mechanism.

The real advantage of the automatic inflatable was brought home earlier this year when Jamie Boeckel was lost overboard off the coast of Connecticut during the Block Island Race. During an all-hands spinnaker takedown in a vicious squall, Boeckel—who was not wearing a harness, having come on deck from his bunk without stopping for his safety gear—was apparently struck in the head by the breaking spinnaker pole, and knocked overboard. Despite heroic attempts to recover him, including another member of the crew diving overboard, Boeckel, who apparently was either unconscious or dead when he hit the water, could not be found.

It’s very easy to second-guess a situation that went wrong, but there are certainly some lessons to be learned here. Had Boeckel been hooked on, he might not have been lost overboard. Had he been wearing a harness with an automatic built-in inflatable, he would probably have floated face-upward in the water, even if unconscious. The harness, of course, should have kept him attached to the boat, so that the overboard situation should never have occurred.

2002 Bermuda Race

Astonishingly, a total of four men were washed overboard during the Newport Bermuda Race just a few weeks after Boeckel’s death. None was attached to the boat at the time, despite rough conditions in most of the incidents. One sailor was wearing a fanny pack inflatable, which he was apparently able to deploy.

All of the sailors washed overboard were professionals. All three incidents—two men went overboard at the same time from the maxiboat Morning Glory—involved sail changes or other sailhandling maneuvers. This is by far the most dangerous time on deck, as it usually means the crew is working with both hands.

Fortunately, all the man-overboard incidents took place in daylight, making recovery far simpler. Aboard Morning Glory, the Man Overboard Module was immediately deployed, giving both the overboard sailors and the boat a target to aim for. Unfortunately, in the high winds and big seas, it was not easy to see the MOM. The MOM’s inflatable pylon has more windage than a traditional man-overboard pole, and may not stand as upright in some conditions. On the other hand, the bright orange inflatable pylon should make a better visual target in most cases, compared to the relatively small flag of a conventional pole. There’s no perfect solution here.

Most importantly, the boats were able to execute the “Quick Stop” maneuver—tacking the boat without releasing the jib sheet—that effectively heaves the boat to before it can travel a great distance. It is most important not to get far away from a person in the water. A boat traveling at 10 knots covers about 500 feet in 30 seconds. For a crewmember in the water, that distance can look like miles. In a big seaway, a person’s head in the water looks very, very small even at a range of 100 yards.

In each man-overboard incident in the Bermuda Race, the lost crewmen were back aboard in less than five minutes, certainly due in large part to the fact that safety regulations for offshore racing require that boats practice such emergency procedures.

Man Overboard Locaters

The huge advantage of the MOM is that it can be instantly launched by pulling a single pin. With the more traditional fixed pole and horseshoe combination, mounting the equipment so that it can be quickly deployed without entanglement can be a problem. On older racing boats, built in the days before the MOM, it is common to see a horizontal launch tube for a fixed pole built into the transom. Cruising boats with fixed overboard gear are more likely to mount the pole attached to the backstay, making quick launching a hit-or-miss affair.

In the 2002 Newport-Bermuda Race, roughly 90% of the boats were equipped with some form of the inflatable Man Overboard Module. Interestingly, the boats from the Naval Academy—a bastion of conservatism in all things seamanlike—still use fixed man-overboard poles mounted in transom tubes.

Cruising Applications

Personally, we have very mixed feelings about using the Man Overboard Module on a cruising boat. When Calypso reached New Zealand in September, 1999, our MOM 8A was a year past due for inspection. When the dealer in New Zealand repacked the unit, he discovered a defective oral inflation valve that effectively rendered the unit useless.

We have no way of knowing how long the MOM had been in that state. Nor could the dealer guarantee that the repair he made would last. In the two years since our unit was last repacked, which included 20,000 miles of sailing, we have no way of knowing that our MOM would in fact do the job that it was intended to do.

For a long-range cruising boat, this is a real dilemma. It’s not unusual for inflatable safety equipment on a cruising boat to greatly exceed its designated time between servicing, just because you may not be somewhere in the world that the equipment can be properly inspected and repacked. A year after our liferaft and MOM were repacked in New Zealand—the time when re-inspection for both was due—we were in the middle of the Red Sea, with nary an inspection station in sight. I can assure you that looking for a re-pack station in Sudan will be a waste of time.

We have heard so many horror stories about bad re-packs overseas that we decided to carry on back to the US without getting either our MOM or liferaft re-certified, which may not have been the best decision. We were confident in the New Zealand re-pack of our raft, and it had not suffered undue exposure, so we felt on fairly safe ground there.

Although our cannister-packed raft is located in the middle of the deck, it is protected from sun and spray by a Sunbrella cover. We used to remove this cover for passagemaking, but have decided that the additional protection it offers the raft more than makes up for the time it would take to rip off the cover if we ever had to launch the raft. After five years and over 30,000 miles of sailing, the canister still looks pretty much like new, thanks to this cover.

Lifesling

Offshore racing safety regulations now require that boats carry the Lifesling recovery system. It is unusual to specify a piece of equipment by name brand, but the Lifesling is such a good piece of gear that the apparent commercial endorsement is justified.

There is one caveat with the Lifesling. The polypropylene line is subject to ultraviolet degradation, and must not be exposed to sunlight. It is critical that the woven protective cover on the end of the yellow line be the only part exposed to sunlight.

Replacement lines are available if you have any doubts about the condition of the line. If the yellow line has begun to fade, replace it. If only the end of the line is sun-damaged, at least cut that part off, and replace the entire line as soon as it’s practical. Shortening the line reduces the effectiveness of the Lifesling.

Conclusions

All of the equipment discussed here has a dedicated purpose: to keep the crew aboard the boat, and to recover a person who goes in the water. We have not discussed the techniques of stopping the boat, getting back to the person in the water, and getting them back aboard.

For a cruising couple, this is a nightmarish scenario: you come on deck for your watch, and your partner is gone. During our circumnavigation, this fear was with us so constantly that it drove us to extraordinary precautions, all geared towards keeping both of us securely tied to the boat at all times. But if, for some reason, someone goes in the water, having the right equipment, and knowing how to use it, is the key to preventing tragedy.