In the early 1800s Norwegian sailors started wearing cork filled vests dubbed the Seamans Friend. And over the next two centuries, life jacket design and the materials used have continued to evolve. One of the most promising offshoots has been the inflatable personal flotation device (PFD)-invented and patented by Peter Markus and one thats drawn our interest for over three decades.

By the onset of WWII, aviators flying over open water had settled on a Mae West style inflatable and a lot of the original research had been done on buoyancy derived from air or CO2. Slowly, sailors grew interested in the technology, but it took innovators like Stephen Lirakis and others, who began combining a safety harness and tether with an inflatable PFD, to really spawn a new generation of life jackets.

The win-win feature of this safety combo resides in how comfortable the inflatable PFD is to wear, the buoyancy it delivers, and how the harness can keep a sailor attached to their boat. The latest inflatable life jacket/safety harness combinations are better than ever. But over the years, reports of inflation failures, bladder leaks and tales of sailors being drowned while dragged through the water have added up. Sailors wearing inflatable PFDs have also been trapped beneath overturned hulls and washed ashore after a grounding-these incidents also added to a growing list of fatalities.

Annual U.S. Coast Guard boating accident reports underscore two very significant facts. The first is that sailing is one of the safest boating activities to be involved in. And secondly, flotation does save lives. Unfortunately, the data becomes murkier when it comes to the best types of PFDs and real world outcomes. Details about inflatable failures remain sketchy and much of the feedback comes from news-grabbing headlines that profile tragic accidents. Whats missing is a tally of the success stories that arise from situations in which an inflatable, or any life jacket for that matter, does its job properly and allows a victim to climb back on board. Sadly, such good news doesn’t often get big headlines. We don’t even have an accurate count of how many boaters fall overboard but are quickly hauled back aboard by an able crew. Fortunately, feedback from race committees, yacht club accident reports, and safety training sessions tally up PFD statistics and help to define the operational reliability of these life jackets.

The U.S. Coast Guard has been cautious about calling a product with no inherent buoyancy a PFD. They require armed and ready indicators on inflation systems and seem to have been quite wise in defining inflatable lifejackets as a manually operated device with an automatic backup. Over the years, marketing efforts and perhaps a bit of over-enthusiasm in the sailing community has altered this perception by referring to these PFDs as auto inflatable life jackets. Many training programs teach sailors to rely on auto inflation as their first line of defense.

This approach disregards the fact that, in most cases, a quick pull of the inflation rip cord will actually inflate the vest faster than it would auto-inflate. The reason that inflatable PFDs have a multiple approach to inflation is simple-auto inflation isn’t a 100 percent guarantee. Concerns over recent failures have caused us to scrutinize how inflatable lifejackets are serving sailors needs. We believe in the old adage about not letting perfect get in the way of very good, but we also want to see if theres more to be concerned about.

Background

The Coast Guards I-V categorization of PFDs (for recreational use) is on its way out and is being replaced by a labeling system more in keeping with International standards. It will likely rank life jackets by buoyancy in Newtons (50/70/100/150/275), which converts to pounds of up-thrust (11/15/22/35/60). But overlaid on these flotation figures are usage factors such as offshore versus near shore sailing, flotation aids for paddle sports, dinghy and one-design sailing. Add in a wide range of throwable devices and other flotation gear, once bunched into Categories IV and V, and one wonders how much simplification will actually occur? Finally, the new rating system must handle both inflatable equipment and PFDs with inherent flotation (foam, etc.).

Fortunately, the USCG has long understood the Achilles heel of inflatable PFDs. They recognized that the person who inadvertently falls overboard, hits the water with a non-buoyant device, and any delay in inflation increases the risk of drowning. Instantaneous inflation has been the goal, and when all works according to design, todays gear comes close to delivering just that. In other words, when all goes well the inflatable delivers just what the cork-filled, Kapok-stuffed, or foam-formed devices have been doing all along. But its the comfort and mobility you find in an inflatable that tips the scale.

Sailors are far more likely to wear an inflatable lifejacket. Immediate buoyancy may appear less significant in a calm, brightly lit swimming pool, where trainees step off the side deck in full anticipation of going into the water. But when a person goes over the side unexpectedly, and is immersed in gasp inducing, cold water amidst a modest six to eight foot seaway, immediate buoyancy is a major game changer.

Inflatable PFD manufactures have responded by building in a three-way approach to delivering buoyancy. But theres a growing debate over how to view the options. Many safety trainers adhere to a linear, three-step approach to lifejacket inflation. The sequence leads off with reliance on auto inflation, and if that option fails, the person in the waters (PIW) second choice is to pull the manual inflation rip cord tab. Lastly, if one and two fail, theres always the oral inflation tube.

Others see a better way to expedite buoyancy. They don’t wait to see if auto inflation will do the job. Instead, they immediately reach for the manual inflation tab and follow the USCG wisdom about an inflatable life jacket being a manually operated PFD with and automatic back up! If both approaches fail, at least you know sooner, rather than later, that its time to rip open the cover and start blowing into the oral inflation tube. The longer you wait, gasping for air and buoyed by zero flotation, the less likely youll be able to orally fill the PFD. Add darkness and roiling sea to the picture and you can see why maintenance and practice with your PFD rank as a high order magnitude.

In our view, pull-the-tab needs to become the sailors mantra. It will turn manual inflation into a muscle memory reflex. If auto-inflation beats you to the punch, thats great. The same accolade goes for just the opposite outcome. Most manual inflation tabs include the four letter word jerk-treat it as a verb, and pull the cord immediately. This delivers a double-barreled approach to immediate inflation. Regardless of whether the manual or auto function wins out, or its a dead heat, you improve your chances of becoming buoyant much sooner.

It’s worth reiterating that in one training session a smaller persons hydrostatic inflatable did not function and she was advised to submerge a little deeper to get it to operate. Increasing how deep you submerge is not the best approach, pulling the manual inflation tab makes much more sense.

Design features

Comfortable to wear should never be the sole criteria in choosing a specific life jacket. Perhaps this attribute will get more people to wear a PFD, but too much focus on the dry-side of PFD design can be problematic. In some cases it has led to inflatable life jackets that are so compact and tightly packaged that auto inflators are slower to respond and the pull-tab is so well tucked away that accessing it becomes difficult. On the other hand, some sailors have complained that when the pull tab dangles like an ornament on a Christmas tree, an inadvertent snag can set off the device.

New Mustang and Spinlock vests have pull-to-inflate features sculpted into the PFDs surface. Users need to become familiar with locating these manual, rip-cord activators, and they should be able to operate it with their eyes closed. You should know which hand to use to grab the release pull cord and on which side of the bladder lies the oral inflation tube.

Other trends in the quest for comfort and compactness is the use of a zipper, rather than Velcro, to more tightly and neatly compact the bladder and close the cover of the inflatable PFD. The result is a neat, easy to wear life jacket. But it means that if neither the automatic nor the pull-tab activation works (as in the case of a bad CO2 cylinder), you must strip open the zipper in order to free up the bladder and inflate the life jacket orally. Most of the new devices label the pull-apart point with lettering and fabric high points to grasp. Fully opening up this seam frees up the bladder, exposes the oral inflation tube and allows a higher volume of air to be blown into the bladder under lower pressure.

If an AIS beacon has been added to the bladder oral inflation tube, and its auto-on system relies upon a string around the bladder, the pressure of oral inflation might not be enough to switch it on. You may need to manually pull the tab to release the antenna and turn on the AIS beacon.

Theres no question that leg/crotch straps improve the performance of an inflatable PFD. It does so by preventing the bladder from riding up and helps to maintain a lower center of buoyancy. This keeps your airway higher and results in less neck constriction. However, these straps are often found to be uncomfortable when seated in the cockpit and many sailors leave them unclipped. This has two major downsides, both related to the tail-like appendages. Firstly, the loose straps can get caught in rigging or snag on other hardware. Secondly, if you go over the side, its quite difficult to find, gather in and reclip the straps, leaving you in the same situation you would face without them. A better alternative is to slacken the straps a bit when youre seated on deck-but leave them clipped. If you do end up overboard, its possible to yank on the webbing and cinch down the PFD.

Many cold water/ cold weather cruisers prefer foam filled float coats with a well reinforce built in harness. These devices provide immediate buoyancy and contribute to heat retention, a big plus when hypothermia becomes a major factor in survival. Ted Parish, a life-long Chesapeake Bay and blue water sailor, has an interesting perspective on PFDs. In his day job as a Master Mariner and Delaware Bay Pilot, he guides ships up and down the confines of the busy estuary. Its a year round cycle and getting on and off ships in winter ups the ante. He recently recounted why he and other pilots have switched back from inflatable PFDs to foam life jackets. Their reasoning revolves around the 100 percent buoyancy reliability provided by inherent flotation. Water temps on the Bay dip below 50F for three or four months of year. And a plunge into such water during a transfer from a pilot boat to a Jacobs ladder, will deliver a physical impact as well as thermal shock. Immediate buoyancy is essential. We arent all Bay pilots, but in a rescue situation, a sailor faces the same steep climb up a Jacobs ladder, and the ship may be rolling in a large, oceanic seaway. Imagine climbing that ladder with a 275 Newtons inflatable life jacket bladder pushing you away from those slippery steps. The point here is to select a PFD/harness that suits your needs in all aspect of its potential use, maintain it carefully and make sure its not in the locker when you need it most.

A growing database

The failure rate at safety seminars is in the single digits, but the sample group is comprised of people who know they are going to be jumping into the pool and are likely to have checked to make sure the lifejackets CO2 cylinder is charged and the ready-to-go indicators are in the green. Several safety trainers walk their students through a DIY life jacket inspection before anyone jumps into the pool. As you might imagine this helps to lower product malfunction as well as operator error. But still auto inflate delays and complete malfunctions occur. Manual (pull-the-tab) failures are closer to nil.

Halfway through a season many inflatable life jackets have gone uninspected. Even more of a concern are the decade-old devices that have never been inflated and remain good-as-new in the mind of their owner. Tucked away in the folds of the bladder are welded, or in some cases, glued seams. The latter will chemically disintegrate, especially in moist, closed up cabin lockers. Most bladder leaks develop on these bonded seams or where oral inflation tubes have been attached to the bladder. Some older jackets incorporated bladders with poor oral inflator reinforcement and bonding.

Prior to the advent of AIS beacons, inflatable PFD manufacturers never envisioned a communications device being attached to their oral inflation tube. If you have an older inflatable PFD, it makes sense to query the manufacturer about connecting an AIS, and its string tension actuator, to the oral inflation tube.

Bladder leaks are a common problem with aging inflatables and, over the years, there have been a number of manufacturer recalls. Check the manufacturers web site to see if there is an advisory or recall affecting your inflatable lifejacket. It also makes sense to do an annual DIY checkup that includes orally inflating the PFD. Leave it overnight and 12-18 hour later check to see if any air has escaped. If it has lost air, test for leaks in a partially filled bathtub by looking for bubbles as you rotate the inflatable. If the leak arises from a seam or the oral inflation tube, the device should be sent to the manufacturer for evaluation and repair/replacement.

Repairing a small pinpoint puncture, not on a seam, may be a DIY job, but when it comes to such vital equipment, referral to a manufacturer or a designated service center makes sense. The lifespan of the equipment varies according to the number of times it has been, CO2 inflated and simply worn and put away wet (spray/rain). Physical abrasion and chemical deterioration, when incorrectly stowed, also has an effect on longevity. The idea that because an owner has never fallen overboard and been saved by his/her inflatable PFD, its still as good as new, is way off the mark.

While I was serving as the Vanderstar Chair at the U.S. Naval Academy, we carried out a test of 30 randomly selected inflatable PFDs (from a group of about 250 units used during summer sail training). These devices were staff checked and the bobbins were changed at the start of the season. They utilized an early version of the Halkey-Roberts auto inflation system. The mechanism was based on a spring plunger that would pierce the CO2 cylinder seal when the replaceable, water-soluble compound held in the bobbin dissolved. During of testing three months later, over 10 percent failed to auto inflate. The ones that did, took as much as 10-seconds to begin inflation.

Ten seconds may seem a very short amount of time, but to a disoriented victim, gasping in cold water-those few seconds can be life threatening. Over the two decades that followed, improvements in inflator design has been significant. But perhaps the most important strides have been made in awareness of the need to train with your life jacket and inspect it on a regular basis. Similar findings in a large scale study were provided in a 2014 report issued by Englands Royal National Lifeboat Institution. It refers to a survey of 6,752 life jackets checked at their training clinics and the alarming statistic that 8.7 percent (587) would not have worked!

Its also important to read the label as well as the user manual that comes with a new inflatable. Some of these life jackets must be worn to count as boat inventory, while others do not. This is often based on the inflator system used.

The USCG favors systems that clearly indicate that theyre armed and ready to be operated. For example, there are lifejackets equipped with the 6F style inflator that must be worn to count as part of the vessels PFD load out. If the same jacket is equipped with a 1F inflator mechanism, the jacket counts toward carriage compliance whether worn or not.

Conclusion

Despite the issues detailed above, we still consider the harness/inflatable PFD to be a cruisers best friend. The reasoning behind our opinion stems from the triple benefit delivered by these devices. The primary one is not buoyancy, its the harness and its ability to keep you from going over the side in the first place. Next comes the benefit of buoyancy and the three ways to instigate inflation.

Lastly, theres the signaling gadgets contained in the folds of the lifejacket, a light, whistle, reflective tape, bright color and even some room for a mirror and an AIS beacon. Yes, all these gadgets can be stuffed into a fanny pack or the pockets of your foul weather gear, and a harness can be worn separately, but with a quick grab of your harness/inflatable PFD-you have it all and youre ready to react to a call for all-hands-on-deck.

Inspecting your PFD requires more than a cursory look a the exterior. The PFD should be inflated and left overnight. If there is any sign of significant air loss, inflate the PFD again and place it in a bath with soapy water and look for any sign of bubbles indicating a leak.

Do not try to repair your PFD on your own as this may void the warranty and put you at risk. Be sure to d register your product to be notified of any recalls.

- Newer vests require you to open the zipper to access the oral inflation tube. Practice this in the dark, with gloves on (if you use them).

- Every automatic inflation vest is actually a manual vest with an automatic backup, and it should be treated as such.

- You should instinctively reach for the manual pull tab the moment you realize you need your vest.

- A clear panel wearer to check the status of the inflation mechanism without opening the vest. It is good practice to open the vest for a full inspection each season anyway

Inspecting your PFD requires more than a cursory look a the exterior. The PFD should be inflated and left overnight. If there is any noticeable sign of air loss, inflate the PFD again and immerse it in a bath with soapy water and look for any bubbles indicating a leak. Except for tiny bladder leaks (not at seams) when there is no other repair option, dont try to repair your own PFD.

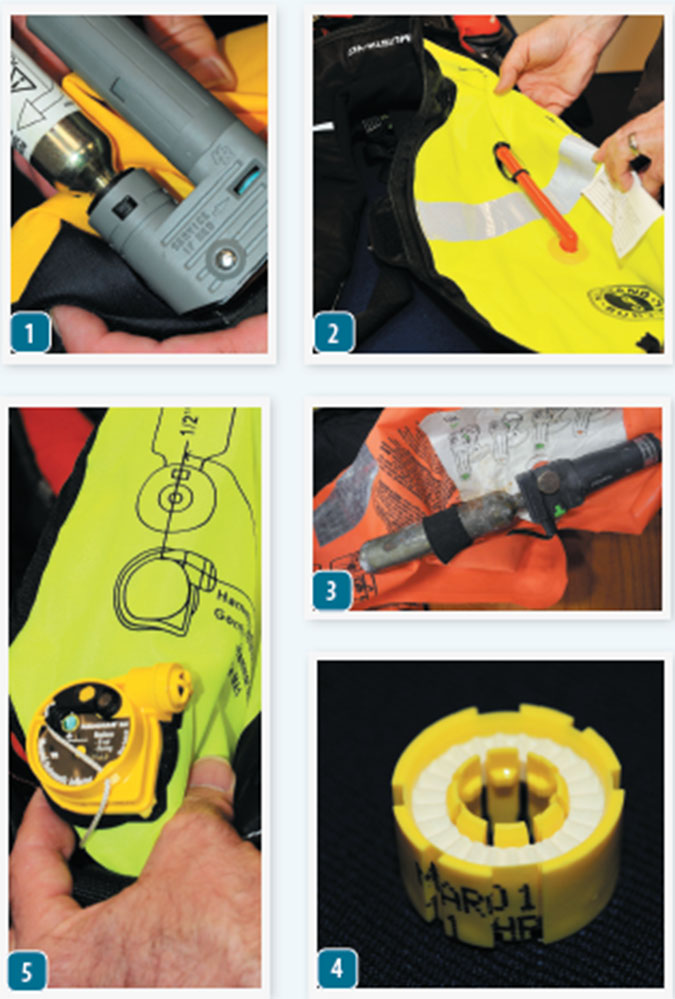

- Halkey Roberts inflators have a green indictor illustrating that the cannister has made a positive connections.

- Every owner should know how to quickly access the manual inflator. Sometimes this inflator is not exposed unless you manually unzip or open the PFD.

- Any older inflatable PFD that shows deterioration should be replaced or sent back to the manufacturer for evaluation.

- Each bobbin is dated used for calculating shelf-life. Check your manual for service life, which varies by model and type of use.

- This Hammar inflator activates on pressure. Newer models of the Spinlock jackets have vent holes in the material to expedite inflation.