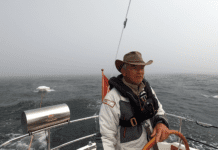

Photo courtesy of Rolex/Carlo Borlenghi

Shortly after 1740 local time on Aug. 15, 2011, Rambler 100-touted as the fastest monohull super-maxi on the planet and representing millions of dollars in research and design-lost its can’ting keel and turned turtle while competing in the 2011 Rolex Fastnet Race. At the time, Rambler 100 was romping along at its usual speed for the conditions-about 22 knots. Sixteen crew suddenly found themselves trying to stay aboard the overturned hull, and another five were in the Celtic Sea with their arms linked, combatting hypothermia.

Fastnet is one of the most prestigious and widely covered events in sailboat racing, featuring the highest echelon of sailors in the world. It is also synonymous with sailing tragedy: Fifteen sailors died in the 1979 Fastnet, the worst sailboat racing disaster in history. Yet it took nearly one hour and 45 minutes after personal locator beacons aboard Rambler 100 were activated for a mayday to be issued. The last person in the water was rescued nearly three hours after the capsize.

In our final review of three sailboat tragedies investigated last year by US Sailing, the governing body of organized sailing in the U.S., we offer a clear look at how even the best-equipped, most highly trained sailors can run into trouble. US Sailings findings in the Rambler 100 accident reinforce several important points raised by our two previous reports.

The existing personal safety gear, including harnesses, tethers, and personal flotation devices (PFDs), marketed to sailors has several critical shortcomings that most sailors are not aware of.

Sailors-from the beginner to the professional-are not getting adequate training for the emergencies they might encounter on the water.

US Sailing would benefit from a standardized report format and procedures for investigating any future sailing accidents.

In the March issue of Practical Sailor, we examined US Sailings report on the events surrounding the tragic death of 14-year-old Olivia Constants, who drowned when the Club 420 she was crewing on capsized during the first week of practice at the Severn Sailing Association (SSA) on Chesapeake Bay. In the April issue, we looked into the US Sailing report on the capsize of the light-displacement boat WingNuts during the 2011 Chicago-Mackinac race, an accident resulting in two fatalities.

Unlike the previous two reports weve looked at, the U.S. Sailing Rambler 100 Capsize Safety Review has only a brief narrative account of the accident. And unlike the two other accidents PS looked at, no one died. The Rambler 100 US Sailing report was directed by Ron Trossbach, a retired U.S. Navy captain and a member of US Sailings Safety at Sea Committee.

The main body of the 12-page report consists of a brief 450-word summary of the accident with a timeline of events surrounding the accident, a list of what lessons U.S. sailors can learn from the accident, and recommendations for improvements to procedures and regulations based on what went wrong before and after the Rambler 100 capsize.

Trossbach, who is also the editor of the U.S. edition of the International Sailing Federation Offshore Special Regulations Governing Offshore Racing, relied primarily on written statements from the Rambler 100 crew (supplied via owner George David) as well media reports, and interviews with individuals involved in the rescue to arrive at his findings. Peter Isler, the navigator of Rambler 100, also offered Trossbach his own more detailed accounts of the accident.

The US Sailing Summary

The following is Trossbachs brief summary of the accident:

[Rambler 100] rounded Fastnet Rock at 1717 local time (BST) and turned southwest for the Pantaenius offset mark (7 miles away) into 23-25 knot headwinds and a sizable (2-meter) short sharp sea. Shortly after the turn, her can’ting keel snapped off just below the hull exit causing her to capsize in less than 60 seconds.Three of the crew on deck were able to climb straight onto the upturned hull as the boat capsized, the remaining eighteen people ended up in the water (14 C/57 F), including four without life jackets who had been down below off watch. In the struggle that followed, 13 more people were able to climb with difficulty onto the upturned yacht while five, including skipper George David, floated away to drift for three hours before being rescued.

After some delay in associating two Personal Locating Beacon (PLB) distress signals with the yacht Rambler 100, Maritime Rescue Sub-center (MSRC) Valentia diverted a Royal Navy Lifeboat Institute (RNLI) lifeboat and a privately-owned dive boat, who were already underway and in the area photographing yachts passing Fastnet Rock, to conduct a search, first for the indicated PLB positions then for the missing yacht. The two PLBs activated were later determined to have been on the overturned hull of Rambler 100.

The sixteen people on the upturned yacht were unsuccessful in hailing several passing race boats in high winds and seas, plus restricted visibility. In addition veering wind caused the layline of approaching racers to shift 300-500 yards right of Rambler 100s port tack and capsize position. They were finally sighted and rescued by the RNLI Lifeboat that was searching for the two PLBs, which were the only two electronic distress signals received.

The five who were unable to attach themselves to the boat because there were no lines that could be reached, managed to tie or hold themselves together until they were rescued by the dive vessel, Wave Cheiftan, diverted from taking photos of boats and vectored by Marine Rescue Sub-center (MRSC) Valentia, who used a search and rescue mapping software system, SARMAP, to predict their set and drift.

Incredibly, everyone was rescued and the shaken crew was taken to nearby Baltimore, except for crew member Wendy Touton, who was airlifted by Irish Coast Guard Rescue 115 helicopter to Kerry General Hospital, suffering from advanced hypothermia and later released. Local residents of Baltimore, Ireland, greeted the shaken crew with genuine hospitality, offering them dry clothing, food.

Of particular interest to Practical Sailor was the length of delay between the capsize and time of rescue in a race of such magnitude, involving more than 300 other boats. One hour and 10 minutes passed between the time when the PLB alerts were first activated and a pan-pan declared by the Valentia MRSC, the regional authority responsible for managing maritime distress. Another one hour and 40 minutes passed before all members of Rambler 100 were recovered safely. This means that the five crew in the water spent two hours and 50 minutes trying to stay afloat in rough 57-degree water. They were lucky. A person can lose consciousness or even die of exposure after spending between one and two hours in 50- to 60-degree water.

PS Analysis

Although the report lacks some emotional punch, the timeline format provides a clearer picture of the events and how they unfolded than either of the two US Sailing reports PS previously reported on. However, the Rambler 100 reports format, in which no one is directly quoted and no names are mentioned, also lacks the depth of detail that can emerge in the individual survivor stories. In the WingNuts incident, the personalized narratives yielded important information about individual experiences with the safety gear.

The Rambler 100 report offsets its rather stripped-down account of the accident with a list of unfiltered advice from the crew of Rambler 100. For example, the first piece of advice from the crew of the Rambler 100 is that the auto-inflate capability on all PFDs be disabled. (See Crew Recommendations.) Although survivors of WingNuts were also critical of the auto-inflation feature in a capsize situation in their statements to authorities, the more-tightly edited WingNuts report did not highlight these comments.

Some safety experts worry that the survivors uncensored advice might be mistaken for recommendations from US Sailing or its experts, but if the source and purpose for sharing this information is clearly indicated, we think the risk of survivors spreading so-called bad advice is one that can be managed without heavy-handed censorship.

As in the previous two reports from US Sailing, Trossbachs list of recommendations is one of the most valuable sections. With regards to safety gear, Trossbachs list is more specific than the previous two reports. While the Severn Sailing Association and WingNuts accident reports call for research on topics such as hiking harnesses (in the Olivia Constants investigation) and tether-release mechanisms (in the WingNuts report), Trossbach offers detailed advice on safety equipment.

He stands firmly behind the generally unpopular crotch strap on PFD-harness combinations. He also points out the problems the survivors had with whistles and rescue strobes, some of which would only work when they were in the water. On the topic of auto-inflating PFDs, however, he leaves the decision in the hands of the sailor: Revisit the decision whether you want to wear an automatic or manual inflating life jacket.

Trossbach recommends all crew wear a survival fanny pack including a PLB, a bright strobe light, and a knife, among other things. We would add that every sailor keep a primary knife in a more accessible location on his or her person.

The report omits some details that Trossbach mentioned during a presentation in Annapolis, Md., last fall. According to Trossbach, Rambler 100s crew were issued emergency fanny packs with PLBs in them, but none chose to wear them. None of the five who found themselves adrift in the water had PLBs. Were it not for the two people who opted to keep their PLBs on their person, the ending might have been tragic.

The report also fails to explain the delayed rescue response. It appears that the PLBs were registered to G.G. Bernard, personal assistant to Rambler 100s owner George David, but when, or if, Bernard was contacted by rescue authorities is not indicated. The timeline also omits any response within the Global Marine Distress and Safety System (GMDSS) until the Valentia Maritime Rescue Sub-Center in Ireland is notified, about 40 minutes after the PLBs were activated. Tracing the rescue response from the time of distress alert until the rescue often reveals glaring flaws in the GMDSS network that sailors need to be aware of. Irish authorities are still investigating the delay.

Bottom line: Of the three reports produced by US Sailing that PS reviewed, this one provides the closest scrutiny of emergency gear and procedures. Trossbachs laundry list of recommendations may be tough for US Sailing to swallow, but the Safety at Sea Committee is not bound to make any changes. Simply raising these issues to the pubic consciousness is important. While the just-the-facts approach lacks the emotional tug of story-telling used in the other two reports, it offers a greater service to the sailors by presenting the essential details uncensored.

Conclusion

The format of the Rambler 100 report has many advantages over the narrative-focused accounts of the other two reports we evaluated. If, as we are urging, US Sailing establishes a more standardized approach to future accident investigations, we would like to see that format replicate the just-the-facts tenor that Trossbach has applied here. Sailing is a small and somewhat incestuous industry, and the more we can do to keep post-race accident reports focused on the facts surrounding the accident, the more helpful these reports will be to all sailors.