Carroll Marine: A Graceful Bow

At the end of June, Carroll Marine—a Bristol, RI boatbuilder and fixture in the sailboat industry for almost 20 years—closed its sailboat manufacturing facility. The boatbuilding complex was sold to Outerlimits, a high-performance powerboat manufacturer who had been one of Carroll Marine’s clients.

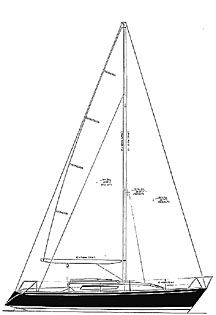

Carroll Marine was an industry success story. Barry Carroll is a Naval Academy graduate who worked as production manager at C&C Yachts back in the late 1970s. In 1984, he and his wife Janice founded Carroll Marine, and began building series-produced racer/cruisers, largely from designs by German Frers. The Frers 33, 38, and 45 were nicely finished true dual-purpose boats, although their IOR-derived hull shapes provided limited interior space in a period when the “caravan cruiser” was just beginning to emerge in the US market.

Dual-purpose boats sound good in principle. In practice, however, most dual-purpose boats are neither fish nor fowl, lacking the competitive edge to be successful racers, and without the space and amenities desired by serious cruisers.

Carroll Marine was uniquely placed when the big-boat one-design backlash to expensive Grand Prix handicap racing took off in the late 1980s. The Mumm 36 was a breakthrough boat that led the way for other Farr-designed, Carroll-built one-designs, including the Mumm 30, Corel 45, and Farr 40 classes.

The relationship between Farr and Carroll was symbiotic: Farr designed and marketed the boats, Carroll built them. As pure one-designs, their construction costs were significantly lower than those of many comparably sized series-produced boats. There were few options, and ballasting the boats to within a few pounds of each other guaranteed that boats were as similar as possible in performance.

For owners frustrated by handicap rule changes and the disparities in cost and performance between “stock” racing boats and highly customized one-offs, the big-boat one-design was the answer to prayers. At the top end, the owner who had spent hundreds of thousands (or even millions) on a one-off which was quickly out-built and out-designed—and therefore practically worthless—could at least expect a slower rate of depreciation on his investment.

At the other extreme, the neophyte or small-budget racer could get on the same race course with the big boys with a rational level of expenditure. He could also get out fairly quickly without getting hurt too badly if the sport proved too rich for his blood.

For better or worse, the entire sailboat industry—and particularly the testosterone-fueled racing sailboat industry—was driven to new heights by the stock market explosion of the 1990s. But when the economy began to contract three years ago, the writing was on the wall.

Sailing is tightly linked to discretionary spending. Reduce disposable income, and discretionary spending drops like a stone. For high-flyers who saw their paper net worth decline by half or more with the stock market’s nosedive, spending on new boats receded in importance compared to paying the mortgage and putting the kids through college.

Yes, there are success stories in every economy, whether it’s good times or bad. Carroll had survived tough times before, but this time was different. But by the time you’re in your mid-50s, long-term plans take different forms. Barry and Janice saw the big picture, and it wasn’t saying that good times were just ahead in today’s sluggish economy.

Like most people who make a career out of the sailing industry, Barry and Janice were in it for the love of boats as much as anything else. Yes, they are both hard-nosed business people with a sharp eye on the bottom line, but they have also given back to the sport in many ways. Barry, for example, is a Rear Commodore of England’s Royal Ocean Racing Club, a group as influential in the management of sailboat racing today as the Cruising Club of America was from the 1930s through the 1960s.

As a reflection of the way they do things, once the decision was made to fold Carroll Marine, the Carrolls sold the assets, made sure that key employees had jobs with the new owners, paid off suppliers, and generally wrapped up operations neatly. This is in dramatic contrast to the way things sometimes seem to be done in the sailing industry, where the first real signs of trouble are unanswered phone calls, a padlock on the door, unhappy owners with nothing to show for the deposits on their dreams, and a host of unpaid suppliers with little recourse.

You can be sure that people with the energy and experience of Barry and Janice Carroll will not sit on the sidelines for long. Although Barry says his short-term goal is to ski all winter and cruise on his powerboat next summer, odds are strong that they’ll be back, and the sailing industry will be better for it.