A Sail of Two Idiots – Tip #1

How Will You Pay for Your Boat?

In 2006 the boat market was still doing pretty well, if you were a seller. An extremely used 35-foot catamaran (about the smallest one ever made) was going for around $125,000 and up vs. similar-sized brand-new basic factory/production monohulls going for around $80,000. Yes, a single hull would have been much cheaper, but we didn't want one.

How will you pay for your boat? There are lots of ways: inheritance, stocks, savings, loans, gifts, banks, hold ups. We sold our house.

In order to come up with how much boat we could afford, we valued our home and took the worst-case scenario (or what we thought was the worst-case scenario - the lesson is coming).

Although we figured we could probably sell the house for enough to pay off a boat, there would be very little left over to actually sell it. We decided to use part of the house proceeds to put down a down payment on the boat (20 percent is standard) and then obtain a no-qualify loan to cover the rest. The remaining home profit would go into a money market fund, which we figured could have us sailing for up to four years.

The numbers looked like this: Sell the house for $340,000. After the commission and loan pay-off, we'd have $199,000. If we put 20 percent down on, say a $125,000 boat, we'd have about $174,000 for our money market fund. That money would cover the cost of our living (boat payments, insurance, food, fun, and boat repairs - that last one should have been listed first). If we figured on spending $50,000 annually on these items, we could expect to be on the sea for three to four years, which seemed reasonable enough. We figured that when we sold the boat at the end of that time, the proceeds would cover the boat and everything would even out. You have to admit it was a good plan (a four letter word), and it sort of happened like that. Sort off.

Lesson 1: Own Up

Was this a good idea? With hindsight, I can now say that I wish we had paid for the boat outright, which would have prevented our obsessing about keeping up its resale value (and obsess we did). Living free of rent/mortgage/debt would have been much more liberating. Had we bought the boat for cash, we could have lived on it while working another year or two to come up with some spending and maintenance money. We also might have worked out the kinks and maybe even learned how to sail while we accumulated more cash. Of course, then I wouldn't have had a book to write.

For more lessons based on her real-world experiences cruising the Caribbean, written in her own humorous, self-effacing manner, purchase Renee D. Petrillo's A Sail of Two Idiots from Practical Sailor.

A Sail of Two Idiots – Tip #2

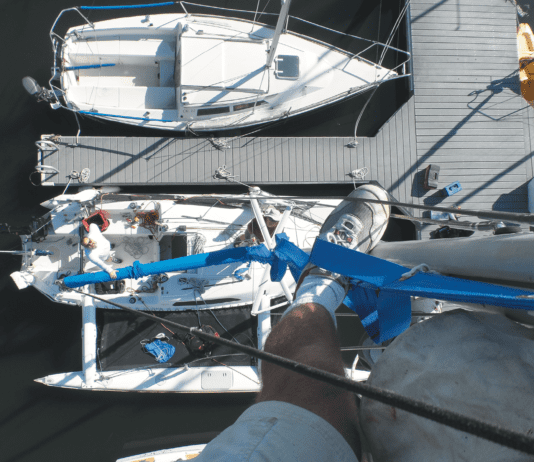

Hauling Out and DIY

While on Grenada, we discovered that our boat insurance was coming due and that the company would require an out-of-water survey this time around. We would need to haul out the boat.

Well, if we were going to do that, wed also make sure the surveyor we hired looked at the boat from a sales standpoint. We knew we were near the end of our journey. We had seen most of the islands and had no desire to go to the western South/Central American coast, and wed had it with those conditions. More important though, we had only enough money for maybe another year. We needed to start thinking about which island could provide a place we wanted to live on and a job to let us stay there.

Assuming wed sell the boat within the next year, and knowing we had to haul it out anyway, we figured we might as well see what our surveyor had to say about the boat, so we wouldnt have surprises during a survey with a buyers surveyor later. (Ha! Boy did that not work, but you have to admit, it seemed logical.)

Just as in the Bahamas, we had a narrow canal to squeeze through to reach the Travelift. Then we were strapped into it and hoisted out of the water. We then made one of the most expensive mistakes ever. We were asked if we wanted the bottom pressure-washed or to just give it a quick rinse. Because Americans often think that more is better, we went for the most powerful option. Our bottom paint had held up well from the Bahamas application, but with the pressure-washing, we watched $3,500 of liquid gold (or blue antifouling paint, in this case) wash into the boatyard. The boat bottom was now nice and clean, all right, but it would need repainting. You do not want to make this mistake.

Lesson 91: Just Say No! If your bottom looks good, and theres a lot of antifouling paint on it, when someone asks if you want it pressure washed - say it with me now - NO!!!!! A light washing with a garden hose will do just nicely, thank you.

For more cruising tips from sailors whove been there, purchase Renee D. Petrillo's A Sail of Two Idiots from Practical Sailor.

How to Sail on a Budget – Tip #1

Hull and Deck Survey

Any worthwhile inspection lasts several hours so even if a couple of boats are situated close together do not plan on visiting more than one boat a day. Take overalls, gloves, a flashlight, a tape measure, ruler, camera, spare batteries for camera and flashlight, a bradawl or sharp penknife, mirror, notepad, pencil and copies of the inventory and photographs that the owner provided. The mirror is to peer into awkward corners and the bradawl is to poke suspicious-looking timber. No boat owner will like you doing this so use it discreetly.

If the owner or broker insists on staying with you once he had opened up the boat then they may offer some explanation or comment every time you make a note or take a photograph. Be non-committal and try not to become involved in any discussion on the points raised but do make a note of his remarks. They may come in useful later when negotiating over the price.

A wise seller has the boat looking as pretty as possible. If it is out of the water, the hull should have been power-washed. Below the waterline there should be new antifouling or, at the very least, any patches of bare hull painted over. The topsides should have been cleaned and polished. Below decks should have had a deep spring clean and lockers emptied of clutter and cleaned to give the impression of a spacious interior with lots of living room. The bilge, if not newly painted (a warning sign in its own right), should be sparkling bright without an oil smear or tide line in sight. In short, everything should have been done so that your first impression is, Wow, this is a great-looking boat! and, so the seller hopes, this thought will blind you to any defects it may have. Your job is the look beyond the shine.

Alastair Buchans book, How to Sail on a Budget, is full of money-saving advice on the best way to buy, maintain, sail and enjoy your sailboat. Purchase a copy here at Practical Sailor.

How to Sail on a Budget – Tip #2

Inspecting the Hull

A boat survey is an important part of any boat purchase.

Look at the hull from as many angles as possible. Does the gel coat look chalky even though it has been polished for your visit? If a dull or chalky-looking gel coat cannot be restored to gleaming brilliance with a light rubbing compound, then the hull needs painting.

If there has been hull damage, a good, professional repair should be invisible but if there is a blemish or deformity in the hulls otherwise smooth curve it may be a sign of a less than competent repair.

Fiberglass does not like sharp angles so if you see one, for example where the hull meets the transom, look to see if patches of gel coat have broken away to reveal voids underneath. Check for stress cracking in the gel coat in and around the chain plates and deck fittings such as the bow roller.

Imagine the boat coming alongside a pontoon or jetty and think of where the hull would bump if the maneuver went badly. Once you have worked this out, check port and starboard for any signs of the topsides having been given a good thwack. If there is a wooden rubbing strip, check it for damage or to see if a new length has been scarfed in. Examine the bow to see if it has had a run-in with a pontoon.

If the boat is out of the water, check the keel for bumps or dents which suggest a close encounter with something hard. Are there signs of rust weeping from where the keel joins the hull? If so, then at the very least, the keel needs to come off and be cleaned up before being replaced. New keel bolts may also be required.

Check the hull for hull blisters. Small bubbles and blisters are the most obvious sign and most common below the waterline. Blisters are not fatal and can be cured but the remedy is costly.

Has the hull been painted? If so, with what type of paint and when? Was it painted above and below the waterline? Two or three coats of epoxy paint below the waterline reduces the risk of osmosis.

Alastair Buchans book, How to Sail on a Budget, is full of money-saving advice on the best way to buy, maintain, sail and enjoy your sailboat. Purchase a copy here at Practical Sailor.

How to Sail on a Budget – Tip #3

Painting the Hull

One way that even an inexperienced boat owner on a budget can save substantial sums during the refit is to repaint the hull themselves. Any owner who has some basic painting skills, plenty of stamina, and attention to detail, can tackle this job, provided that he or she use the correct materials and follow the instructions given. The secret of success is in meticulous preparation; you can use the very best paint system but if your preliminary work is not done thoroughly enough, and you apply the paint in the wrong atmospheric conditions, then you are actually wasting money not saving it.

Alastair Buchans book, How to Sail on a Budget, is full of money-saving advice on the best way to buy, maintain, sail and enjoy your sailboat. Purchase a copy here at Practical Sailor.

Sailboat Refinishing – Tip #1

Inspecting the Hull

When choosing a wood finish, knowing the pros and cons of each finish type is helpful. One- and two-part varnishes are clear, hard coatings that offer a deep, classic mirror-like finish. Prep, application, and re-application are more labor-intensive than with other finishes and require a more skilled hand, but they usually need less frequent maintenance and are more durable.

The top selling point for varnish alternatives is their ease of application: They require fewer coats than varnish, dry faster, and require little or no sanding between coats. The softer, flexible finishes need to be re-applied more frequently than varnish and generally do not last as long, but re-application and maintenance are a breeze. Although some can be overcoated with a glossy sealer, they don't have the high-gloss finish of a hard varnish and often are pigmented. These opaque stains mask the woods grain somewhat but are touted as offering better UV protection than traditional clear varnishes.

Teak oils and sealers are favored for their ease of application, nonskid properties, and resistance to blistering. They are not as durable as other finishes and require frequent re-application, but they are easier to maintain. Teak-oil critics say they attract dirt and encourage mold and mildew growth, which we found to be true in some of our test panels. (For more pros and cons of various wood coatings and a wood finishes primer, view the online version of this article at www.practical-sailor.com.)

For even more expert advice on how to finish your boat, purchase Don Caseys Sailboat Refinishing from Practical Sailor.

Sailboat Refinishing – Tip #2

What is the best substance to use on a cabin sole? Will Interluxs Cetol products work well?

As with all wood-finishing techniques, there are a million different "best" coatings for a cabin sole-the answer just depends on who you ask. Advice runs the gamut-from using the same urethane clear-coat recommended for basketball courts and bowling alleys to leaving it natural.

According to Interlux (www.yachtpaint.com), its Cetol products can be used on cabin soles, but we do not recommend using them. Cetol Marine, Cetol Marine Light, and Cetol Marine Natural are relatively soft coatings and will not last long or wear well with the amount of traffic a cabin sole sees. The Cetol gloss overcoat is not as hard of a finish as most urethanes, so it would offer less protection but just as much slipperiness as a hard varnish.

What type of finish you choose greatly depends on what the sole is made of. If its a thin veneer on plywood, a hard, protective, urethane varnish is the best alternative. PS editors have had good luck with Interluxs polyurethane Goldspar Satin and Epifanes High Gloss and Wood finishes (www.epifanes.com). The products have also scored well in our past tests.

Urethane varnishes will leave a slick, ice-rink like surface, though, so its a good idea to also use a nonskid additive.

One tried-and-true technique for this on teak-and-holly soles is to use ground walnut shell powder. (You can find it at larger boat yards, paint supply companies, and Harbor Freight.) After building up a uniform series of base coats, place -inch masking tape over the centerline of the -inch holly strips, and then mix the powder in the final coat of varnish. This results in nonskid stripes that are near in color to the teak, with enough of the sole left glossy to add a warm feel to the cabin. If you plan to add this or any other nonskid material to a finish, be sure to run it by the varnish companys technical crew before applying it.

If the boat is blessed with a solid teak sole, varnishing can be avoided. To keep the teaks natural warm look and good nonskid, use a penetrating wood sealer (Interlux or other). To maintain it, clean it with Murphys Oil Soap regularly and reapply the sealer as necessary. Every few years, a little block sanding will renew the surface.

Another product, Ultimate Sole (www.ultimatesole.com), is a dedicated cabin sole finish. Its an oil-modified urethane designed to have slip resistance and a high gloss. We have not yet tested it, so can't recommend it, but we would appreciate feedback from any reader who has used it.

Alastair Buchans book, How to Sail on a Budget, is full of money-saving advice on the best way to buy, maintain, sail and enjoy your sailboat. Purchase a copy here at Practical Sailor.

Sailing Without Centerboard – Tip #1

Sailing a Dinghy without a Centerboard

Centerboards or daggerboards rarely break (although it is possible to lose a daggerboard during a capsize if is not secured to the boat). However, it is useful to try sailing without one so that you can see just how much they influence the way a dinghy behaves under sail. Stop the boat on a close reach and raise the centerboard completely. Now sail off on a beam reach and watch the way in which the boat slides sideways, making considerable leeway as it sails forward.

Tacking is difficult or impossible without a centerboard to pivot around. Before attempting to tack, get the boat sailing as fast as possible on a close reaching course and push the tiller away farther than usual to try to get the bow through the wind as quickly as possible. If, despite this, the boat fails to tack, you will have to jibe around to change tack.

On upwind courses it is hard to make headway because the dinghy will crab sideways as fast as it goes forward. Experiment with heeling the boat to leeward slightly and moving the crews weight right forward to depress the bow and the Veed sections of the front part of the hull. If you sail a deep-hulled, general-purpose type dinghy, especially one constructed with flat panels and chines, the shape of the hull may provide sufficient lateral resistance to allow you to make some progress to windward. If you sail a dinghy with a very shallow hull, however, it is likely to be impossible to make any progress upwind. Even on a beam reach, the boat will make considerable leeway. It is only when you are on downwind courses, when the centerboard would usually be only slightly down, that the boat will sail normally.

Steve Sleights The Complete Sailing Manual, covers every aspect of sailing and seamanship, whatever your level of experience. Full of hundreds of pages of tips and advice like the information above, The Complete Sailing Manual is sure to help every sailor. Purchase it at Practical Sailor.

Sealants – Tip #1

Stop That Leak!

Modern chemistry has presented us with new choices of sealants for everything, including the kitchen sink.

The trick is to choose the right one. Some sealants get hard enough to sand or drill, and others stay supple. Some will stick to anything; others pull away from glass and certain plastics. Some will writhe and stretch as your boat works. Others crack. And some, designed for household use, wont hold up in the harsh heat, cold, wind, and ultraviolet light your boat is subject to.

There are six major sealant types, all with special uses. Read the labels to be sure, but a good marine sealant should perform as follows:

Bedding Compounds

Many boatbuilders still use bedding compounds such as Interlux 214 for bedding deck hardware, cleats, padeyes, flanges and more. The surface of this bedding compound hardens to allow painting, but stays flexible underneath the surface to provide a flexible waterproof seal. Bedding compounds will tend to dry out over time and hardware will need to be re-bedded.

Silicones

Sticks to almost everything including glass, electrical insulation, and most metals. Ideal insulator and waterproof for wiring including trailer wiring, windshields and ports, and emergency gaskets in applications where temperatures don't exceed 400 degrees F. Dont use with polypropylene, under water, or in areas where you want to sand and paint. Not as good as polysulfide in areas that take a lot of twisting, compression, contraction, and expansion. They are generally safe to use with most plastic glazing, including Lexan and acrylic (Plexiglas).

Polysulfides

Use above and below the waterline. Can take up to 25 percent stretching, twisting, expansion and will bond difficult surfaces including oily woods, aluminum, and glass. (Read directions for possible surface preparation steps.) Can be sanded and painted. Available in liquid form to ease filling of hairline cracks. Drawback: takes up to 10 days to cure in a humid climate; longer in dry climate. If youre not counting on it as a waterproofer, you can launch the boat right after caulking because water speeds curing time. Other caulks cure faster

Polyurethane

Polyurethane sealants and adhesives have grown in popularity and are preferred by boatbuilders for projects like sealing hull-to-deck joints and installing through-hulls. The long-chain molecules that crosslink in the curing process include isocyanate resin that reacts with moisture to form a flexible solid. These highly adhesive polymers offer both excellent surface grip and desirable gap-filling characteristics. There are numerous formulations that lead to products with different cure rates, elongation characteristics, and tensile strength.

Polyether-Based Caulks

These are the newest genre of ultra flexible gap-filling adhesive/sealants, and their cure is dramatically accelerated by a more reactive methyl silyl-enhanced reaction with water vapor that causes polyether products to skin cure faster than silicone and deep cure much quicker than polyurethanes. Their lack of solvents eliminates odor and minimizes shrinkage-based skin stress. They have very favorable stretch capacity and good resistance to ultraviolet rays and weathering.

Butyls

Cure fast, stick well, can be used on polypropylene where polysulfide cannot. Not sandable, but can be painted. Easy to apply, and cures to supple rubber.

Acrylics

Ideal for bedding on wood, fiberglass, metals. Skins over quickly and can be painted after half an hour; full cure in one to two days. Water soluble which means easy water clean-up but also that its not suitable for underwater use.

For more information on choosing the right sealants and how to apply them, purchase This Old Boat, Second Edition today.

Sealants – Tip #2

Stop That Leak!

Modern chemistry has presented us with new choices of sealants for everything, including the kitchen sink. The trick is to choose the right one and apply it correctly. Here are some hints on application:

- When trying to form an even, good-looking bead with polysulfide, coat your fingers with liquid detergent and you can mold the sealant, after it skins over, without sticking.

- Most pros pull a bead of caulk because of the control it offers. A good bead in the first place is better than the finger and detergent approach described above.

- Polysulfides cure faster when wet. To speed up curing, adjust hose nozzle to fine spray and keep sealant damp. For smaller areas, use a spray bottle.

- Sometimes a primer is needed before applying sealant to some surfaces. Read labels carefully so you can buy needed primers and solvents before leaving the store.

- Its best to avoid caulking in cold weather. Both the caulk and the boat should be in moderate temperatures for the best result.

- Use underwater caulk on through-hulls to insulate, not just against leakage but against galvanic corrosion.

- Marine polysulfide sealants help keep engine mounting bolts from corroding or vibrating loose, and ease future removal. Put some on the threads before turning the nuts down.

- If you carry an extra tube of marine silicone sealant aboard, you can jury rig any size gasket.

- When making a hatch gasket from silicone sealant, place a bead on both surfaces, then cover with waxed paper and close hatch. Paper keeps gaskets separate as they cure.

- Coat back sides of light fittings to seal wire ends (but not light bulb socket) to prevent corrosion.

- For proper adhesion, seams in teak decking should be at least l/&I-inch wide, l/4-inch deep.

For more information on choosing the right sealants and how to apply them, purchase This Old Boat, Second Edition today.