Photos by Drew Frye and courtesy of Colligo

Fiber shackles have been in use for centuries-the simple knotted toggles provided all manner of service on square-riggers and even older craft. When made correctly with the right material, fiber shackles are strong, can be released without tools, and are jam-proof in the most severe weather. Like cotton sails, this 200-year-old technology has been updated through the use of modern materials.

Our recent test of halyard shackles (see PS September 2014 online) offered an excellent look at how far along soft shackles have progressed since the age of sail. Todays versatile soft shackles are not only impervious to corrosion, but they can match the strength of steel. Here are just some of the pros of using soft shackles in place of more traditional stainless-steel or silicone-bronze shackles in some applications.

- Soft shackles wont scratch gelcoat, toe rails, sail cloth, or lines. They wont put a dent in your mast or the head of your foredeck crew.

- They don’t loosen in use or require mousing.

- They can be tied to many sizes and lengths.

- They are easier to handle than knots or shackle-pins when you are wearing gloves.

- The are flexible, even twistable, so they eliminate the need for swivels.

- You don’t need any tools to remove or to install them.

- They are cheap. You can make one yourself in about five or 10 minutes for only a few dollars each.

- They are strong. A soft shackle can be twice as strong as the line its tied to, depending on style.

- They are light. Light weight is handy everywhere, but is especially useful for jib clews, halyards, and anything else used up high in the masthead.

- But of course, they also have their weaknesses.

- They can chafe through. You need to smooth down any sharp metal edges that a soft shackle attaches to-especially any steel hardware. (Aluminum is softer, so using soft shackles on toe rails and headboards is usually less of a problem.)

- They can’t be released under load. You need to slacken whatever a soft shackle is attached to before releasing it, and even when a sheet or guy is slack, it can be difficult to release a soft shackle from a flogging sail.

- Soft shackles are vulnerable to damage from ultraviolet rays. Dyneema, one of the most popular materials for soft shackles, loses about 5 percent of its strength annually.

- Soft shackles are bulky. They are generally larger than stainless D-shackles.

As with any new technology, you need to recognize which uses are best suited for this type of equipment, and when the positives outweigh the negatives. Racers and splicing enthusiasts now apply fiber solutions to almost every problem, but for the most common applications, steel shackles remain the right choice for most sailors.

An anchor shackle, for example, is a poor application for a soft shackle. Light weight and removability arent important for an anchor shackle; and the chance of a fiber shackle being severed on the anchors rough shank or something on the bottom is unacceptable. However, there are a few applications where even cruisers are finding the benefits undeniable.

Popular Applications

Genoa sheet attachment: While most sailors are well served by either knots or a spliced-eye that is cow-hitched to the genoa clew, soft shackles offer a better option, if you are frequently swapping sails or removing sheets. Steel shackles are lethal to the crew and can really ding-up a spar, and knots can snag when tacking. Weve been using soft shackles on the end of eye-spliced genoa sheets on one of our test boats for two seasons now, and they have proven to be safe, reliable, and snag-proof. For material, we suggest using at least 1/8-inch Amsteel or 3/16-inch, if there is room. The larger size makes for easier handling.

Chain-snubber connection: Attaching the snubber to the anchor chain is always awkward. It requires leaning over the pulpit in bouncy conditions, which is probably why were seeing more new varieties of chain hooks appear on the marine market (see PS January 2015 online). However, while most varieties of chain hooks and knots are not easily deployed over rollers, a simple soft shackle slips right over a roller without hanging up.

Will the soft shackle chafe on the rough chain? Contributing writers Beth and Evans Starzinger, who wrote about extreme anchoring for us in 2008 (see PS November 2008 and December 2008 online) have used this technique to attach their snubber and have not found it to be a problem. Be sure to use an open-style soft shackle (one with an oversized loop), as they are less prone to jamming with marine life. Line diameter for the soft shackle should be at least 50 percent that of the chain link; for example, with 5/16-inch BBB chain (breaking strength 11,600 pounds), a soft shackle made with 3/16-inch Amsteel fits and has a breaking strength of about 8,640 pounds. While this is not as strong as the chain itself, it is stronger than the typical snubber line and is considerably stronger than a grade 43 chain hook (5,400 pounds). And if you like an extra measure of security, there is nothing wrong with going up in size. It will not release on its own as some older chain-hook designs can do.

Tie downs: Soft shackles are a great choice for securing tarps, sail covers, life rings, and deck gear-or for simply attaching halyards when they are not being used. For many lower-strength applications, soft shackles can be constructed from nylon or polyester, either tied, sewn, or spliced from scraps. Though knotted toggles may look less secure, weve never had one come off; testers have used these for 25 years on tarps and never had one fail, even in the windiest conditions.

Halyard shackles: We looked at several of these in the September 2014 issue, and still have a variety of Dyneema halyard shackles undergoing long-term testing. So far, all of them are holding up well, although some designs are just as difficult to set as a simple screw-pin halyard shackle. Soft halyard shackles are especially popular with racers and owners of performance multihulls; but for ordinary cruising, we still prefer a high-quality bronze or stainless-steel shackle.

Mainsail clew straps: Clew straps can help keep the clew of a furling, loose-footed, or reefed main tight along the boom. Although Velcro webbing straps are more commonly used for this purpose, Amsteel is easier to pull tight because it is more slippery. It is also more resistant to ultraviolet rays than Velcro. Typically, a 6-foot to 8-foot length of 3/8-inch or thicker diameter Amsteel is eye-spliced at both ends. One end is cow-hitched around the boom and clew, and the rest of the line is wrapped until it is taught and then secured with a soft shackle.

A second rode: In some places with reversing currents and limited swinging room, a Bahamian moor-in which a secondary anchor is set at a 180-degree angle from the primary-a soft shackle can be used to connect the second rode below the snubber of the primary. This diminishes the degree of tangles (though not the twists) that this anchoring arrangement often produces.

Other uses: The sky is the limit: barber haulers, twing blocks, cunninghams and tack pendants, attaching reefing blocks to clews, sail hanks for fiber stays.

Soft Shackle Tips

Because making a soft shackle is more easily described by video than in words or pictures, the online version of this article has links to some of the most helpful, knot-tying videos we have found. The videos include demonstrations for tying a regular soft shackle and the Edwards improved soft shackle, as well as a demonstration of a tool weve found handy, the D-Splicer (although an ordinary knitting needle works almost as well). A couple of our tested splicing tools (see PS July 2006 online) are also well suited for the job. There are, however, a few tips that are worth pointing out here:

- Use pliers or a vice to tighten the diamond knot at the end of the shackle so that it is rock-hard; otherwise, it will draw into the shackle under extreme load. Leave a tail in this knot, or melt a big blob with the tail so that the knot will hold its shape. An Ashley stopper knot (see link to video in online version) is simpler to tie than the diamond knot and works on a single polyester or nylon line. (Dyneema is too slippery.)

- The open-style (Edwards) shackles are easier to open and are preferred where frequent removal is required. They are just as secure as the closed style, which use a small line to open and close around the knotted end.

- Longer shackles are generally more versatile than shorter ones, and they are easier to tie.

- When making a shackle, be careful to open the center fully when burying one line inside the other; if the fid snags even one thread, the line will not pull through.

- The most important factor (after a tight diamond knot) is achieving an even balance on the two strands that make up the shackle. One trick is to lock the strands with stitching or a pair of pass-throughs (brommels) before tying the stopper. (See online video links for demonstration.)

- A short velcro wrap, occasionally added for some applications, keeps the diamond knot out of the way. It is optional and has no effect on strength or security.

- The added noose (used to close the spliced loop) is not needed for soft shackles made with polyester; a simple knotted toggle is less trouble to use and wont come off, if properly sized to fit the stopper. Dyneema is too slippery, however, and benefits from a noose.

Even though soft shackles have been used for more than two centuries, sailors are constantly inventing new uses. If you have found interesting or novel uses for soft shackles and would like to share them, send us an email at [email protected]. If you are sending photos as well, please be sure to send high-resolution images (minimum 300 dpi), so we can print them in the magazine.

Dear Sir:

This is Sia Xi from Yangzhou HYropes Co., Ltd.

Our factory is very experienced in producing rope in China.

We can produce

Size: 0.5mm and above

Material: Kevlar, Dyneema ®, nylon, etc.

MBL: By your requirement

Linear Den: by your requirement.

Color and package can meet your requirement.

If you can provide samples or pictures that we can according to your requirements. And then offer.

Regards

Sia

One superb application for a Dyneema loop Not mentioned in the article has great appeal to those of us who like our four-sided sails, i.e. owners Of gaff-rig sailboats. Do I need to loops make idealReplacements for the traditional mast hoops, I don’t like the traditional hardware, never jam going up or down!

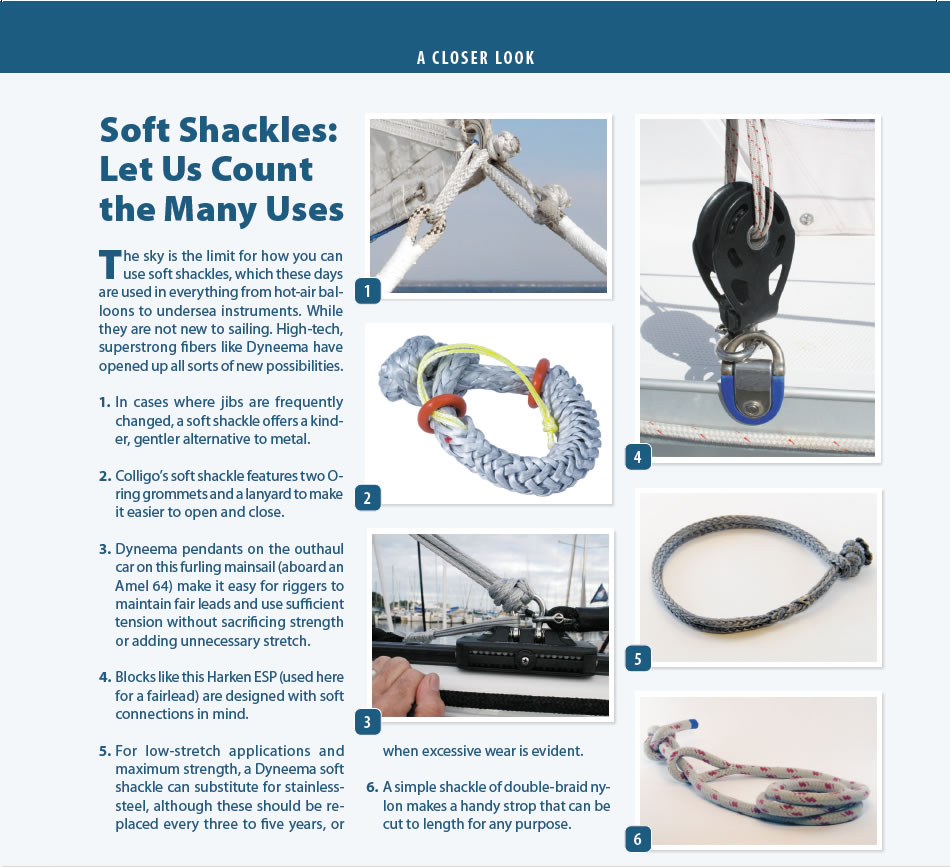

One superb application for a Dyneema loop not mentioned in the article has great appeal to those of us who like our four-sided sails, i.e. owners of gaff-rig sailboats. Dyneema loops make ideal replacements for the traditional mast hoops Unlike the traditional hardware, these loops never jam going up or down!

Unfortunately, voice recognition technology completely garbled my comment and there is no provision for editing after the fact. I will attempt to post the “revised“ version here:

One superb application for a Dyneema loop Not mentioned in the article has great appeal to those of us who like our four-sided sails, i.e. owners of gaff-rig sailboats. Dyneema loops make ideal replacements for the traditional mast hoops, Unlike the traditional hardware, these loops never jam going up or down!