Storm Prep – Tip #4

Despite the fact that modern forecasting methods are far from perfect, a large storm almost always is tracked with enough precision to let you know whether youre potentially in the path of destruction. With warning of a few days or less, you don't have a lot of time to take the precautions necessary to give your boat the best chance to survive a major storm, so it's best to make an action plan well ahead of storm season.

Windage

When the load exerted on a boats ground tackle-whether a mooring or her own anchors-exceeds the holding power of the ground tackle, the boat will drag. One of the primary contributors to that load is the windage of the boat.

If your boat hung perfectly head to wind, the windage loading would be fairly small, consisting of the frontal area of the hull, deck structures, spars, and rigging in the case of a sailboat. Unfortunately, few boats lie perfectly head to wind through a storm. Instead, they yaw about from side to side.

As the boat sails around on her anchors or mooring, the total area presented to the wind, and hence the total loading on the ground tackle, varies dramatically. The area presented by any boat broadside to the wind is several times that presented by the same boat when it is perfectly head to wind. Since the change in wind loading is a function of the square of the wind velocity, the strain on your ground tackle increases geometrically as the boat yaws around. Reducing windage will help reduce the total loading, and hence help your boat stay put.

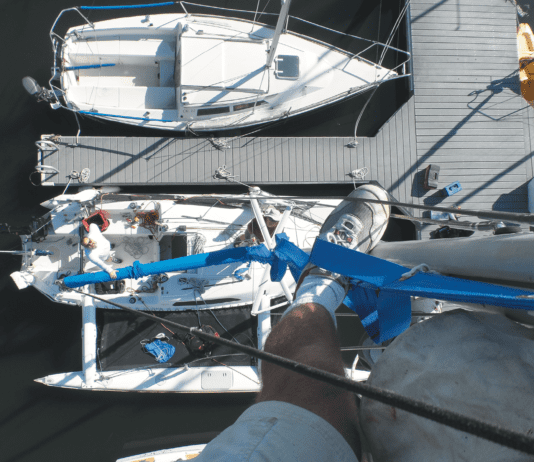

You can substantially reduce the windage of any boat with only a few hours of work. First, remove bimini tops, cockpit dodgers, spray curtains around cockpits, and awnings. Those are pretty obvious. The rest may not be. Sails should be removed, particularly roller-furling headsails. You don't just have to worry about the windage of the rolled-up sails; you have to worry about what will happen when the sail unfurls. And we practically guarantee it will, no matter how well tied it may be.

Mainsails should be removed for the same reason. If the sail is so big that you can't handle it yourself, and you have no one to help, add extra sail ties, and thoroughly and tightly lash down the sail cover. The normal securing system of the sail cover and the normal amount of sail ties used are not adequate to hold the sail in place during a major storm. If the sail gets loose, it will at least flog itself to death. At worst, it will add enough windage to make your boat drag its ground tackle.

Take off man-overboard gear, cockpit cushions, cowl vents, antennas, and halyards, if the halyards can be removed easily. Internal halyards can be run to the masthead, leaving a single halyard led to deck to allow you to retrieve the others after the storm. No matter how well you tie them off, halyards will flog the hell out of your spars, in addition to creating added windage. Likewise, masthead instrumentation may simply blow away, particularly your anemometer cups.

For more advice on preparing your boat for an upcoming storm, purchase out Bill Seiferts Offshore Sailing, 200 Essential Passagemaking Tips today!

Storm Prep – Tip #5

Anchored Out

Boatowners who have the option of moving their boats to protected water before a hurricane strikes should consider rivers, canals, or backwater creeks instead of marinas. If the site is a narrow canal or river, you may be able to run multiple lines ashore to trees or mangroves on both sides. If the waterway is wide, you can also anchor.

Marine-industry professionals advise using helix moorings, but there are some other anchoring techniques that can work as well. The key is to use more and larger anchors, and those that are appropriate for the type of bottom. Boats have survived hurricanes when anchored with two anchors with unequal-length lines set 60 to 90 degrees apart.

Another arrangement consists of using three very large anchors set 120 degrees apart with the rodes leading to a central pennant. Note that each anchor must be capable of taking the full load.

A tandem anchoring system, where a second anchor is attached to the first one via a length of chain, adds additional holding power. With any of these systems, some kind of snubber-like length of nylon line must be incorporated into the chain rode(s). Deep-water anchorages will see less wave action than shallow ones, allowing the chain catenary to absorb some of the load.

Whether your vessel is moored or anchored, chafe will be a certainty if the storm hits, so proper chafe protection is imperative. Also, if your boat will be riding the storm out on a mooring, make sure the chain, swivels, and pennant on that mooring have been checked recently for wear.

The following is a two-anchor mooring system Practical Sailor Technical Editor Ralph Naranjo has used with success in various locations to moor his 41-foot Ericson sloop, Wind Shadow. At the heart of the system are two sets of ground tackle:

- A 45-pound CQR, with l0-millimeter (3/8-inch) all-chain rode, 3/8-inch nylon snubber, and leather anti-chafe gear.

- A Paul Luke 75-pound, three-piece fisherman storm anchor, 50-feet of 1/2-inch chain, 200-feet of 3/4-inch nylon, leather anti-chafe gear (no swivel).

Set the two anchors at about a 60-degree angle, placing the storm anchor opposite the worst of the expected wind and fetch. Leave enough swinging room to cope with the likely wind shift, which could be as much as 180 degrees. No swivels! Both anchors and rodes provide great reset ability. Make sure the cleats and deck can take the load.

A mast on a modern sailboat is not meant to be a bollard. Use the winch pedestals and sheets as a safety back up. Make sure scope can be added and use the engine to alleviate strain if crew remains aboard.

For more advice on preparing your boat for an upcoming storm, purchase Bill Seiferts Offshore Sailing, 200 Essential Passagemaking Tips today!

Storm Trysail – Tip #1

A storm trysail rarely gets the close look it deserves. Designed to replace the mainsail in a severe storm, it spends most of its life in the sail locker.

The sail is required by offshore race rules and is a must for ocean-voyaging boats, but most modern production boats arent even set up for a trysail.

The trysail hoists on the mast, but must be capable of flying independent of the boom. To make setting the sail as easy as possible, the boats mast typically has a separate parallel track for the trysail. Feeder tracks that route the trysail into the mainsail track can work in some cases, but are generally less desirable. Stand-off tracks for in-boom furling, as well as some stack packs, and static lazy-jack systems can complicate a retrofit.

Trysail sheet blocks should be mounted port and starboard, allowing the sheets to lead fairly to a winch. Snatch blocks are not the first choice for this job.

It is best to work closely with a sailmaker and/or the boats designer to get the right size and shape trysail. It should be cut flat, and the center of effort located to optimize stability and helm balance.

For more advice and recommendations on sails - what to buy, carry and use, purchase Practical Sailor's downloadable ebook A LOOK AT SAILS, PART TWO: Headsails & Furling Gear.

Also, check out the complete 3 volume series, PRACTICAL SAILOR'S A LOOK AT SAILS - Complete Series at a price that gives you one ebook free when you buy the other two.

Survival Electronics – Tip #1

Anyone putting blind faith in their 406 EPIRB should consider two recent incidents in which registration numbers were somehow incorrectly added to the United States 406 MHz beacon registration database. These apparent clerical errors ultimately delayed rescue missions. The concern over additional miscues has prompted the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA) to encourage beacon owners to check their registration data online. The easy-to-navigate website www.beaconregistration.noaa.gov offers step-by-step guidance.

For more information on the best types of electronics to survive an emergency and how to use them, purchase Practical Sailor's downloadable ebook Survival Electronics.

To read more about how to best prepare for an emergency on the water, purchase and downlaod Survival at Sea - The Complete Series at a price that gives you one ebook free when you buy the other two.

Survival Electronics – Tip #2

Without question, a 406 EPIRB should be the mainstay of your distress signaling game plan. Its a tried and proven system with worldwide coverage, and it has been in place long enough to work out most hardware bugs. Despite a less-than-perfect record, it remains a mariners best first choice. Whether to choose an auto-deploying model or a manually activated unit is a tougher question to answer.

The external water-sensing contacts and control magnets on Category 1 units can create a false alert. Additionally, violent seas can sweep a Category 1 EPIRB out of its bracket. Even so, auto deployment may be the best bet in the chaos of a collision or capsize. Many sailors prefer to keep a manual unit in an easily accessible ditch kit or grab bag, but climbing into a life raft and leaving the beacon behind can have catastrophic consequences.

For more information on the best types of electronics to survive an emergency and how to use them, purchase Practical Sailor's downloadable ebook Survival Electronics.

To read more about how to best prepare for an emergency on the water, purchase and downlaod Survival at Sea - The Complete Series at a price that gives you one ebook free when you buy the other two.

Survival Electronics – Tip #3

Nearly all new EPIRBs feature an internal GPS receiver, a big advantage in an emergency. Once satellites are acquired, these units will send a lat/long fix as well as enable position tracking via Doppler shift. ACR offers a dual GPS unit that eliminates the lag time in position reporting caused by delays during initial satellite signal acquisition. The EPIRB is interfaced with the onboard GPS, keeping the beacon aware of the current position, and allowing the first emergency signal burst to carry an accurate lat/long.

Bottom line: In an emergency, a GPS-equipped EPIRB is well worth its capital outlay. Be aware that the batteries for some older models are very expensive or have been discontinued, so units that use these batteries might not be the bargain they appear to be.

For more information on choosing the best types of electronics to survive an emergency and how to use them, purchase and download Survival Electronics.

To read more about how to best prepare for an emergency on the water, purchase and downlaod Survival at Sea - The Complete Series at a price that gives you one ebook free when you buy the other two.

Teak – Tip #1 (Snippet cut – Tip Too Long to Save)

Teak: A Little Effort Goes a Long Way

Probably nothing can make or break the appearance of a fiberglass boat more quickly than the appearance of the exterior teak trim. Contrary to popular belief, teak is not a maintenance-free wood that can be safely ignored and neglected for years at a time. Though teak may not rot, it can check, warp, and look depressingly drab if not properly cared for.

If your teak is dark brown from old, oxidized dressing, or weathered grey from neglect, the first step is a thorough cleaning.

The severity of the discoloration of the wood will determine the severity of restorative measures required. Because cleaners containing acids and caustic are hard on the wood, you should try to use as mild a cleaner as will do the job, even though it may take some experimentation and a few false starts to come up with the right combination of ingredients.

The mildest teak cleaner is a general purpose household powdered cleaner such as Spic n Span. A concentrated solution of powdered cleaner and vigorous scrubbing using a very soft bristle brush or, better yet, a 3M pad, will do a surprisingly good job on teak that is basically just dirty. Don't scrub any harder than you have to, and always scrub across the grain. Every time you scrub the teak, you are removing softer wood, which eventually results in an uneven surface that raises the grain. Regularly using a firm brush to scrub with the grain will lead to problems down the road.

The advantage of a gentle scrub using mild cleaners is that while it is more work for you, it is by far the most gentle for your teak. Since you are likely to have some powdered detergent around, always try this method before going on to more drastic measures.

Simply wet down an area with water, clean with the detergent solution, rinse with fresh water, and let it dry. If the wood comes out a nice, even light tan, youre in luck. If its still mottled or grey, a more powerful cleaner is called for.

The next step is a one part cleaner specifically designed for teak, or the equivalent. These can be either powdered or liquid. Most consist of an abrasive and a mild acid, such as phosphoric acid or oxalic acid. They are more effective in lightening a surface than a simple detergent scrub. Many household cleaners like "Barkeeper's Friend" contain oxalic acid.

If the cleaner contains acid, however, some care in handling must be taken. It is advisable to wear rubber gloves and eye protection using any cleaner containing even a mild acid.

The cleaning procedure with most one-part cleaners is the same: wet the teak down, sprinkle or brush on the cleaner, scrub down, and rinse off. Be sure to rinse well.

Even badly weathered teak should come up reasonably well with a one part cleaner. When the wood dries, it should be a uniform light tan. If some areas are still grey, a repeat cleaning should do the job. If, however, the teak is still mottled or discolored, the time has come to bring out the heavy guns, and with them the heavy precautions.

The two part liquid cleaners are, with only a few exceptions, powerful caustics and acids which do an incredible job of cleaning and brightening teak, but require care in handling to avoid damage to surrounding surfaces, not to mention your own skin.

While the instructions on all two-part cleaners are explicit, a reiteration of the warnings on the labels is useful.

Adjacent surfaces, whether gelcoat, paint, or varnish, must not be contaminated by the cleaners, most of which can bleach gelcoat or paint, or soften varnish. Constant flushing of adjoining surfaces with water while cleaning is usually adequate, but masking off of freshly painted or varnished surfaces may be more effective.

Hand protection, in the form of rubber gloves, is absolutely essential. In addition, do not use these cleaners while barefooted, and preferably not while wearing shorts. Eye protection is also a good idea. The chemical burns which can result from some cleaners can be disfiguring and painful. If the product label has the key words caustic, corrosive, or acid, wear protection and avoid splashing!

There is slight variation in the instructions for the various two-part cleaners, but the general principles are the same:

- wet the teak down;

- apply part one (the caustic), spreading and lightly scrubbing with a bristle brush;

- when the surface is a uniform, wet, muddy brown, apply the second part (the acid), spreading with a clean bristle brush - apply and spread enough of the acid to turn the teak a uniform tan;

- rinse thoroughly, and allow to dry completely.

Teak – Tip #2

Teak: A Little Effort Goes a Long Way

Probably nothing can make or break the appearance of a fiberglass boat more quickly than the appearance of the exterior teak trim. Contrary to popular belief, teak is not a maintenance-free wood that can be safely ignored and neglected for years at a time. Though teak may not rot, it can check, warp, and look depressingly drab if not properly cared for.

For best results, you should never let your teak trim get to the point that drastic measures are called for. Once you get it back to "like new" condition, you should be prepared to put in the time and effort required to keep it in that condition.

To look its best, exterior teak needs frequent attention. With a boat used in salt water, frequent washdowns with fresh water will prolong the life of the dressing, but scrubbings with salt water and a brush will reduce it.

Horizontal surfaces, such as hatch covers, will require more frequent coats of sealer than vertical surfaces, such as companionway dropboards. High traffic areas like a teak cockpit sole will require the most attention of all, but are the easiest to scrub and retreat, since sanding is not usually desirable.

If all this sounds like a lot of work, that's because it is. That explains why the exterior teak on so many boats looks so grubby.

It is still, however, less work than maintaining a varnished exterior teak surface - a lot less. If you really think you want varnished teak, try maintaining a clean oiled surface for a season first.

Few things look better on a boat, particularly a white on white fiberglass boat, than well-maintained exterior teak trim. An owner who neglects exterior wood is likely to be the same owner who rarely changes the oil in the engine, and who rarely bothers to put on the sail covers after a day's sail when he expects he's going sailing again tomorrow.

Owning a boat isn't all play. A boat is a major investment, and like most investments, the more attention you pay to it, the more it will return. The time you put into maintaining your exterior teak is well invested. The return is not only pride of ownership, but dollars in your pocket when the time comes to sell the boat.

For more tips on how to properly maintain your boat's exterior teak appearance and quick and easy answers to routine boat maintenance problems, purchase Boat Maintenance: The Essential Guide to Cleaning, Painting, and Cosmetics today!

Varnish – Tip #1

Bubbles are one the banes of the varnishers existence. If they break while the varnish is still wet enough, they cause no problems, but if they don't break until after the varnish has begun to set up, they create depressions that look something like the craters on the moon. Avoid bubbles by remembering you are working with a paintbrush, not scrub brush.

Dont apply from the original can, instead pour small quantities into a separate can or plastic cup and refill as needed. Wipe your excess varnish at the start of each stroke gently on the inside of the container. When you wipe your brush on the rim it aerates the bristles; thus you not only foment drips down the outside of the can, you foster bubbles.

For more than 1,000 tips, suggestions, evaluations, and nuggets of hard-won advice from more than 300 seasoned veterans, purchase Sailors' Secrets: Advice from the Masters today!

Varnish – Tip #2

When choosing a wood finish, knowing the pros and cons of each finish type is helpful. One- and two-part varnishes are clear, hard coatings that offer a deep, classic mirror-like finish. Prep, application, and re-application are more labor-intensive than with other finishes and require a more skilled hand, but they usually need less frequent maintenance and are more durable.

The top selling point for varnish alternatives is their ease of application: They require fewer coats than varnish, dry faster, and require little or no sanding between coats. The softer, flexible finishes need to be re-applied more frequently than varnish and generally do not last as long, but re-application and maintenance are a breeze. Although some can be overcoated with a glossy sealer, they don't have the high-gloss finish of a hard varnish and often are pigmented. These opaque stains mask the woods grain somewhat but are touted as offering better UV protection than traditional clear varnishes.

Teak oils and sealers are favored for their ease of application, nonskid properties, and resistance to blistering. They are not as durable as other finishes and require frequent re-application, but they are easier to maintain. Teak-oil critics say they attract dirt and encourage mold and mildew growth, which we found to be true in some of our test panels.

For more information and advice on the products and methods to use to create stunning brightwork, purchase Rebecca Wittmans The Brightwork Companion today!