Folding Kayak

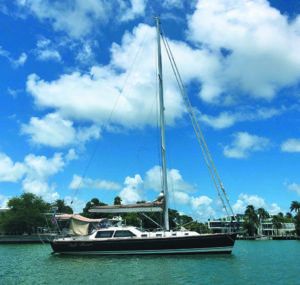

I urge you to consider the Oru folding kayaks in your next Kayak Update. They’re more expensive than the inflatables you reviewed, but a great option for those of us with smaller boats. Mine, Turtleheart, is an Island Packet 27, with no extra deck space for storage. The Orus are easy to assemble and disassemble, and they handle well when the water’s smooth (the only time I kayak!). I’ve enclosed a photo showing my two Oru kayaks stowed (and secured) under my saloon table and a second photo showing one in use on a week-long cruise my brother and I took from Mamaroneck to Fishers Island, stopping at some of the many fine places to kayak along the way.

Michael Luskin

Turtleheart, Island Packet 27

Scarsdale, NY

Thanks for your letter. We’ll try to arrange a trial. Given the popularity that the folding Porta-bote still holds among sailors, we’re not surprised that innovative companies like San Francisco-based Oru have found a niche in the cruising sailing community (see PS September 2000, “Uninflatable Tenders: Two Alternatives to RIBs & Roll-Ups”).

Kudos to AB Inflatables

I recently got out my aluminum collapsible oars to row my AB 10 a very short distance to shore, and “Snap!” One oar broke in half. I contacted 84 Boat Works in Fort Lauderdale from whom I bought the boat some 18 months ago.

I managed to coordinate communication between them and AB Inflatables in Suffern, NY. Headquarters asked that the dealer confirm my purchase and provide my hull number. Last night, my new oar arrived at my home. There was no charge for the oar or for shipping. AB required neither that the old oar be returned nor even a photo. Kudos to John at 84 Boat Works, AB Inflatables and Gabrielle in AB’s customer service department for their help and standing behind even a minor accessory.

Rich Loebl

Safe Haven, Tartan 4700

Coral Gables, FL

Passivating Stainless

I spent 30 years in a chemical plant where most things were made from stainless steel and later titanium. Stainless steels passivate spontaneously in oxidizing atmosphere. They do not need a dip in nitric acid for the formation of a passive film, but all stainless steels probably need a pickle to remove iron contamination from the fabrication and handling. We maintained two massive tanks for pickling, one was nitric acid the other was nitric and hydrofluoric acid. The nitric was used for 400 series and most 300 series were pickled in the nitric and hydrofluoric acid. Nitric acid is not aggressive enough to remove welding discoloration. Keep up the great studies.

Kenneth G. Budinski

Bud Labs

Rochester,NY

Fall is a good time to tackle do-it-yourself projects and onboard maintenance or systems upgrades. It’s also when many of us will shop for that next “new” boat.

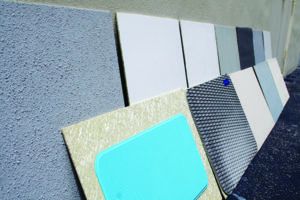

Do-It-Yourselfers

Here are a few worth DIY projects tackling in the off-season. We detail building a simple winter boat cover frame in the September 2011 issue. For those with tired-looking decks, be sure to check out our reports on nonskid options for the do-it-yourselfer (PS November 2013); these include mats and paints. Have an electronics installation or rewiring project on tap? Get some pro tips for rewiring (PS July 2016). If you’re looking for a boatyard where you can actually do the work yourself while hauled out, you can find a rundown of DIY-friendly boat yards (PS June 2009), as well as a list of reader-recommended DIY yards in the Oct. 29, 2013 Inside Practical Sailor blog post. Other good cool-weather projects worth considering: fuel tank cleaning (blog post, June 6, 2018), sail cleaning (blog post, Dec. 6, 2016), making your own chafe guards (PS July 2011), and building your own dinghy wheels (blog post, August 15, 2017).

Boat Shopping?

In the market for a new-to-you boat? We highly recommend reading our checklist for DIY boat surveys (PS June 2012 online) and our “Sailor’s Guide to Marine Insurance” (PS October 2012 online). Cruisers should also be sure to check out the April 2009 issue’s look at cruising boats over 35 feet long and under $75,000, “Affordable Cruising Sailboats.” If you’re considering a boat that’s well-weathered (or possibly storm damaged), the January 10, 2017 blog, “Buyers Beware of Post-storm Bargains,” is also useful.

PS’s Exclusive Ebooks

Our new three-volume water report will ensure that your crew will stay healthy and hydrated with clean, fresh-tasting water straight from your tanks. Volume One compares the most popular water filters on the marine market, and describes some cost-saving do-it-yourself options. In Volume Two you’ll learn secrets to ensuring that your water supply remains clean and good-tasting throughout your voyage. In Volume Three, you’ll see the results of our head-to-head testing of the major brands of watermakers sold today. Available at www.practical-sailor.com/products.

Halyard Mystery

I have sailed for 47 years and have seen lines fail under great stress, but I have never experienced what happened on Friday evening on Long Island Sound, in 12 knots of wind. My main halyard just popped as I was tightening the luff.

I was using an old Barient 21 in low gear, tailing with my left hand and cranking without great force with my right. Honestly I don’t think there was more than 150 pounds of tension on the line when it popped right where it exited a rope clutch.

I know the line was due for replacement, but I inspected the entire length at the end of last season and there was no sign of chafing, and the spot where it failed was visible whenever the sail is hoisted.

The line is an HMPE core, double-braided line. It was used as the main halyard on a J/29 fractional rig and is rigged with a 2:1 purchase.

It was on the boat for about 10 years, but the boat sat on the hard for a couple of seasons. I purchased the boat in 2016 and I don’t know where the line is sourced.

Robert Zimmerman

J/29

Larchmont, NY

I have subscribed to Practical Sailor for years. Although I have a power boat, I like your philosophy for thinking small. You may use this info as you see fit.

Porthole Screen Project

My porthole screens were starting to deteriorate after 10 years. The old screens were a fiberglass mesh. I looked into replacements, but could not be sure of pothole manufacturer or their exact size. What I did find seemed to be quite expensive at $40 to $50 each.

I decided to use bronze window screen as a replacement. This costs about $3 per square foot, purchased at a hardware store. I used plastic sign material for the screen frame. This costs about $6 for the heavier “No Parking” sign (18” x 24”).

- Initially, I cut a dummy frame, using the outside of the old screen as a pattern. It took a little trimming with scissors, but finally got the dimensions right and popped it into the porthole frame. I had cut a couple of 1-inch diameter holes in the plastic so I could handle the dummy from one side.

- Using the overall dimensions from the dummy, I cut four frames on a table saw. I layed out and cut the inside curved sections of the frame, using a 3-1/2” hole saw. I then cut between the edges of the holes to form the opening. I trimmed the outside corners to match the old.

- I cleaned things up with a Dremmel tool and spray-painted both sides with flat black, which was compatible with plastic.

- I cut the bronze screen with scissors to fit the frame, backing it off about 3/8-inch from edge of the frame.

- I weighed the screen down with cans of olives (soup will also work), and glued the perimeter of the screen to the frame with a good quality Super Glue.

- I made the edges of the new frames wider than the old frames since I eliminated the frame’s “center post.” The new screens popped right in with the glued side of the frame on the inside. To remove a screen, it may be helpful to have someone push the frame from the inside.

The new screens should last for years.

David Bogdanoff

Beauty 27

San Francisco

Your experience offers a good reminder about the importance of routine inspection of halyards and running rigging—and the importance of a backup safety line for anyone going aloft! We suspect that physical damage, UV and perhaps chemicals (acid rain) weakened the halyard to the point of failure. There is also a slight chance that there was some construction defect in the core, or that this was simply a cheap knock-off double braid.

In this rope, it is the core that carries to load, so the warning signs are hard to detect. We noticed some fused fibers in the cover, as well as some necking of the core. According to Samson Ropes, both of these are signs of shock loading, sustained over-loading, or heat damage that can weaken the rope. (https://samsonrope.com/docs/default-source/default-document-library/warning-insert.pdf). The core may have at some point been physically damaged, possibly by an oversized rope clutch. If the halyard had been flipped end-to-end during its life, the core fibers might also have been damaged as they passed over the masthead sheave. (Using fiber rope on a v-shaped sheave designed for wire is a common contributing cause to halyard failure.) In addition, UV rays can penetrate the cover, damaging the core over time. We’ve seen this on 12-strand HMPE ropes, in which the top 1/3 of fibers show UV damage. Finally, on some constructions there is the chance that there is a weakness in an internal splice. This has been cited as the cause of some failures. The lack of significant fraying in the sample that you sent us suggests some form of physical damage in addition to overloading.

You estimate the halyard was under just 150 pounds of load when it broke, but during the rope’s life it was likely under much higher loads. With your Barient 21 and a 2:1 purchase, if you apply a moderately high force to your winch handle, you could put 1,000 pounds of load to your halyard. Even half that load, 500 pounds, is high relative to the minimum breaking strength of a halyard that old.

We estimate that the 3/16 inch core of your rope when new had a minimum breaking strength of 4,900 pounds. This gives you a safety factor of ~ 5:1 (4,900/1,000). Halyards often have 7:1 safety factors or higher, and 12:1 is a common spec for lifting.

Based on our research, HMPE fiber lifelines can lose 30 to 50 percent their strength in just five to eight years. So, with no other damage, the breaking strength of your 10-plus-year-old HMPE halyard is near 2,500 pounds, giving you a safety factor of just 2.5:1.

In the wooden box where I keep letters and a few small mementos of 10 years aboard Tosca, there’s a hand carved bottle stopper that Larry and Lin Pardey gave to me 20 years ago. Made of walnut and cork, it looks like a raindrop that naturally sprung from a tree.

My partner, Theresa and I were walking along Bowen’s Wharf in Newport, RI, where I’d come to interview for a full-time job at Cruising World, when we spied a familiar boat, Taleisin. We’d barely exchanged introductions when Lin and Larry invited us to lunch.

To a couple of young wooden-boat sailors who’d been guided for years by the famous cruising couple’s “go simple, go small, go now,” philosophy it was like being invited to tea with the Queen. To this day, I believe that chance meeting was what led me to this spot today.

I can’t remember the words, or which of them said it, but their message was something like this: “If you’re going to settle down, working for a sailing magazine isn’t a pretty good place to land.” What they didn’t tell us was that they were on the verge of hatching a plan to sail westabout sail around the Horn.

Many years later, on assignment for PS, we met again at the Wooden Boat Show, in Port Townsend, Washington where the couple were giving a series of talks. Larry walked slowly, supported by Lin. Parkinsons disease was setting in.

We sat down for lunch once again, on a beautiful Port Townsend afternoon, with a who’s who among ocean sailors, Ralph Naranjo, Steven Callahan, Brion Toss, Carol Hasse, and Lin and Larry. I reminded Larry how’d he’d had a hand in the two biggest choices in my life—to go to sea and to return—and he laughed.

“I hope you made the right choice.”

Larry died in New Zealand on July 27, but the gifts that he and Lin gave to the cruising community—the articles, the videos, the books, the stories—will endure for years to come.

What delights me most about their work is the life wisdom they weave between the practical advice. One bit in particular rings true with me: As long as you are following your dream, you will never make the wrong choice.

Ultimately, your modest attempt to snub your luff probably pushed your old, weathered halyard to its “natural” breaking point given its age and history. A construction defect may also be at fault, but this would presumably show up earlier in the rope’s life.

Determining the condition of running rigging on a new-to-you boat can be difficult. Many experts advise replacing HMPE standing rigging every 5-7 years (although much longer life is common). For running rigging exposed to the elements year-round, we would apply this to halyards as well. You should also consider replacing your halyard with a larger diameter line to better match your clutch and increase the safety factor. Buy only from a reputable supplier of marine ropes. Coatings like RP25 can also prolong life and prevent wear.

For more on this topic, download the November 2010, November 2016, March 2015, and September 2019 issues at www.practical-sailor.com.

Practical Sailor welcomes reader comments and questions. Send email & reader photography (digital .jpg 1MB or greater) to [email protected]; include your name, homeport, boat type, and boat name. Send any broken gear samples to Practical Sailor, 1600 Bayshore Rd., Nokomis, FL 34275