A personal rescue strobe is a small signaling light intended to be attached to a PFD so if a boat crew member goes overboard, their position will be visible to those left on board. Since we last looked at personal rescue strobes theres been some new developments in the intensity of the light that can be generated from a small handheld strobe (see PS February 2016). Strobes can be manual or automatic (water activated) and each type has drawbacks. In this era of personal locator devices like AIS beacons the value of such lights cannot be overlooked especially during the actual rescue, when a visual fix on the victim is essential.

Requirements and Standards

According to the World Sailing Offshore Special Regulations for 2018 – 2019 Governing Offshore Racing for Monohulls & Multihulls, all crew on vessels in near shore, offshore and trans-ocean races must have a life jacket with an emergency position indicating light in accordance with either ISO 12402-8 or SOLAS LSA code 2.2.3. In addition crew on trans-ocean racing vessels must carry two packs of mini-flares or two personal location lights, one of which is to be attached to, or carried on, their person when on deck at night.

The International Standards ISO 12402-8, which governs personal flotation device accessories, sets out requirements and testing standards. It requires that an emergency light be robust in construction, capable of being affixed to a PFD so that it is above the surface of the water when in normal use, and not affect the performance of the life jacket or cause injury to the wearer.

The light emitted by the device must be white and provide a minimum luminous intensity in all directions of the upper hemisphere for a period of 8 hours. A flashing light must flash 50 and 70 flashes per minute for the full 8 hours. Any light must start functioning within two minutes of operation and reach the minimum luminous intensity within five minutes.

The light is required to operate between −30 C and +65 C, withstand water to a depth of one meter for a period of 24 hours and still operate adequately, and be capable of withstanding a drop test and still operate.

The light must be marked clearly and indelibly with the manufacturers name or trademark, its approval, date of manufacturing and expiration, batch or lot code, instructions on how to activate the light, indication if lithium battery is used. If the space is too small this information must be available on packaging or elsewhere from the manufacturer.

In addition, the USCG 46 CFR 161.012 Personal Flotation Device Lights states that approved lights must be visible from a distance of at least one nautical mile on a dark clear night.

USCG requires also that each component of a light remain serviceable in a marine environment for at least the storage life of the lights power source. The light must fit into a cylindrical space 6 inches long and 3 inches in diameter not weighing more than 8 ounces. And if designed to operate while detached from a PFD it must have a lanyard at least 30 inches long that can connect it to the PFD.

What We Tested

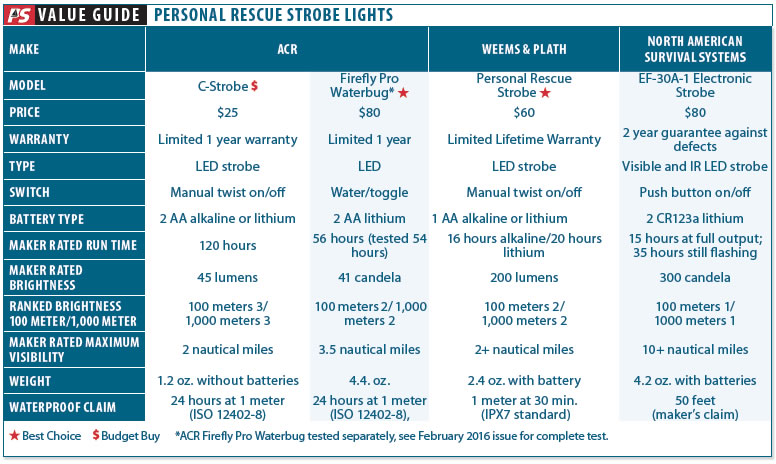

We last tested personal strobes in 2016, and recommended the water-activated ACR Firefly Waterbug Pro. Since that time some new strobes have been introduced to the market including the Personal Rescue Strobe from Weems and Plath and the EF-30A-1, an upgraded version of the EF-20A-1 from North American Survival Systems that we tested in 2016.

The current test, meant to update our previous work, focused on the EF-30A-1 and the Weems & Plath Personal Rescue Strobe, but for a baseline we also included the C-Strobe from ACR, a Florida-based company that has been manufacturing rescue beacons for several decades. All three strobes were manually activated. Manual strobes have the advantage of not being accidentally triggered by water, but their potential weakness lies in the switch, of which certain types can be vulnerable if exposed to water.

How We Tested

Our test relied primarily on field-testing to evaluate visibility. To test the three strobes we first set up a 100-meter course along a beach and let each strobe drift individually out into the water attached upright on a life jacket. (Strobes are generally intended for signaling in low-light conditions and all tests were done late in the day either just before or just after all light left the sky.)

The 1,000-meter test was performed over water. Strobe features that figure into effectiveness are brilliance and pattern of flash, which is made up of flashes per minute and length of flash. Sixty flashes per minute is generally accepted as good for attracting attention.

Observations

All the strobes are pocket-sized (5 to 6 inches), light and small enough to be folded into an inflatable PFD or attached to a life jacket. The strobes met most of the markings requirements. Both the C-Strobe and the Personal Rescue Strobe are Coast Guard approved and show the approval number and manufacturing date. Only the EF-30A-1 does not have activation instructions on the case, but its push button is fairly obvious.

The C-Strobe and the Personal Rescue Strobe depend on the user to twist the lens cap to activate; the C-Strobe has a positive on position and the Personal Rescue Strobe has to be tightened until it flashes. Even so, its not easy to twist a lens cap in the water with cold fingers or to twist one-handed unless the light is rigidly secured with your body or PFD to twist against.

Both the C-Strobe and the Personal Rescue Strobe could readily attach to a PFD, though the Personal Rescue Strobes use of wire ties for attachment to the inflation tube is a bit gimmicky though effective. The EF-30A-1 does not come with attachment equipment, nor does its 6-inch lanyard meet the Coast Guard specifications. The manufacturer indicated that the strobe can be tied to a PFD strap with user supplied string. All three are capable of 360-degree illumination, so they meet the requirement of 180-degree arc when attached to a PFD.

All three began to flash on activation the first time they were tested. They all flashed around 60 times a minute, in the middle of the required range. The results of distance were mixed, and will be described under the test. The Coast Guard standards indicate a required distance for visibility; the ISO standards do not, rather focusing on luminosity, or intensity of the light.

Both C-Strobe and Personal Rescue Strobe passed a water immersion test, remaining waterproof and continuing to flash. After some problems with initial units which were corrected, the EF-30A-1 passed the water test.

Both C-Strobe and Personal Rescue Strobe passed the drop test. While two of the EF-30A-1 units also passed, the lens cap fell off when the third was dropped on that end.

ACR C-Strobe

ACRs C-Strobe is a very inexpensive, simple yellow 5-inch cylinder with clear half-dome lens, opening side loops for velcro strap, and a means to attach to a PFD inflation tube. It is relatively heavy with two batteries and easy to activate once youve read the fine print on the lens cap. Its smooth plastic may be harder to grip when wet.

ACR is a large company founded in 1956, and makes many survival products used by military, government, and consumers. Made in China and USCG and SOLAS approved, it takes two AA batteries. The manufacturer says they can be either lithium or alkaline though this isn’t indicated on packaging.

At 100 meters the C-strobe was clearly visible but duller than either of the other strobes tested. The 100-meter test was repeated in fog, and one tester found the C-Strobe easier to see because of its slightly slower flash than either the sharp quick flash of the W&P or the very bright EF.

At 1,000 meters the C-Strobe was visible but both testers said that if they werent looking for the light, or if surrounded by other lights, it could be missed. One tester had trouble identifying the C-Strobe at all at this distance.

The C-Strobe is an updated version of a PFD light that has been around awhile. It is not bright over distance. Its chief advantage is its price; at $25 the C-Strobe is cheap enough to buy in bulk and carry in numbers. It requires 2 AA batteries which are easy to replace.

Bottom Line:Though not remarkably bright it functioned very well in close quarters and would be helpful in marking a MOB when a rescue is in operation, though not as certainly in locating a MOB.

Weems & Plath Personal Strobe

The 5.75-inch Weems & Plath Personal Rescue Strobe is immediately different in look from the traditional PFD light, with a long cone-shaped polycarbonate lens cap etched inside to refract the light and containing a light cone reflector, and a short bright red, easy to grip plastic battery container body with closed side loops for velcro strap. It activates by common method of twisting the lens cap and uses one AA lithium or alkaline battery. Founded in 1928, Weems & Plath has a long history of serving the recreational and commercial sectors. The Personal Rescue Strobe is made in the USA and USCG and SOLAS approved.

The Personal Rescue Strobe has a sharp, quick-seeming flash and was clearly visible to all testers at 100 meters. At 1,000 meters one tester found the strobes flash pattern and brilliance to be very visible. Another tester found the pattern and light to be more visible than the ACR, but rated its overall visibility as marginal.

The Personal Rescue Strobe is considerably brighter than the C-Strobe and its sturdy construction recommends it for general use as a PFD light. Based on testers visual assessment, the new cone lens does not enhance brilliance as much as one might expect based on marketing literature, but it did create a distinctive triangular beam that some testers found easier to identify. It uses one common AA either a lithium battery or alkaline, making battery replacement easy.

Bottom Line: The Personal Rescue Strobe represents a definite upgrade on the manual twist-switch small PFD strobe. The fact that its range was limited may be a function of the limits of the class of equipment rather than this individual piece. At $60 it is expensive enough that one wants a reliable unit, and this proved itself sturdy and waterproof.

NASS EF-30A-1

The EF-30A-1 from North American Survival Systems (NASS) is made of orange anodized aluminum textured for good grip and looks and feels heavier than the plastic models. It has a clear half-sphere polycarbonate lens and an array of LED and infrared (IR) LED lights and reflectors. (According to the maker, the IR function enhances visibility to IR night vision systems used by rescuers. We did not test this.)

It has a push-button switch with orange rubber cap on the bottom of the cap which unscrews to replace batteries. It takes two CR 123A lithium batteries, less common than AA batteries, but the maker claims that the longer shelf life (up to 10 years) and better resistance to corrosion make them more cost-effective. The EF-30A-1 is assembled in the US. Though it lacks certification, NASS claims it will meet US Coast Guard and ISO standards, and is pursuing USCG approval.

At 100 meters the EF-30A-1 was brilliant. At 1,000 meters the testers agreed that the EF was still bright, brighter than either the C-Strobe or the Personal Rescue Strobe. Both testers agreed that this strobe would be noticed even by someone not looking for it.

All strobes were less noticeable in the fog, which also diminished the EFs relative brightness. One problem with having an exceptionally bright light is that it can blind the victim as well as the rescuers. Testers had to be careful to look away from the light to avoid being blinded.

North American Survival Systems says its goal is to provide maximum performance in a life safety product. The current findings show the strobe to be by far the brightest tested. It is relatively expensive ($80) but its clear advantage in brilliance makes it a good choice if the problems are ironed out-as the maker claims they have. (We have one light in long-term testing and will report any new findings.)

On the face, the EF-30A-1 switch would seem best. It employs a recessed push button on the strobe base, which is easy to activate, even with one hand, but it also can be accidentally activated.

But there are solid reasons for twist activation and against push buttons, as testers discovered when the EF-30A-1 began flickering two days after the in-the-water test, and would not switch off due to a faulty switch.

According to Jim OMeara, owner of NASS, The problem was that our supplier selected a new switch and it did not bottom out against the inside of the rubber push button. All caps with that switch style came to us assembled and would have failed due to a faulty ground contact or water leakage. All production now has the new style switches.

To be safe, Practical Sailor strongly encourages anyone who purchases or owns this light or its predecessor, the EF-20A, to check the switch for proper function. We checked an EF-20A from a previous test and it passed drop tests and immersion test without any problems and remained as bright as ever.

Interestingly, a light that we purchased online from Landfall Navigation prior to OMearas intervention, appeared to have the problem switch, but it performed without flickering even after the immersion test. It did not, however, pass the drop test. In that test, the lens cover fell off. According to OMeara the lens cover is epoxied on, the company has since upgraded the construction to prevent this from happening.

Two lights of six NASS lights that we ultimately tested had the new switch, and passed all tests without problems. According to OMeara these two lights are the only ones among those that we tested that represent the current stock. All of the others have been taken off of the market, he said. The current stock of lights, like all of the ones we tested, had epoxied-on lenses. A mechanical retainer would offer more reassurance.

Bottom line: This is a very bright light, and it appears that North American Survival Systems has addressed the switch concerns and is making continued improvements. U.S. Coast Guard certification is also something the company is pursuing. If you have this light confirm with the maker that it has the correct switch and lens cover.

Conclusion

All strobes were clearly visible at 100 meters, though not equally; the C-Strobe was dullest, the Personal Rescue Strobe next in brightness and the EF 30A-1 was brilliant. At 1000 the differences were very apparent.

The brilliance difference between the strobes tested was clearly distinct, but brightness alone is not the issue. One could break down MOB rescues into two rough categories: those that are or can be handled by the boat and those that expand to include outside rescuers.

The first is experienced by deepwater sailors, the second is more likely among coastal sailors. Can it reasonably be said that if a MOB drifts further than 1,000 meters from the boat, the possibility of rescue by that boat diminishes quickly? If so, then the added brilliance of the EF-30A-1 over the Personal Rescue Strobe really comes into play in a longer rescue scenario.

The brilliance comes at a cost; as the name indicates, the strobe is actually the equivalent of a flare and the packaging says to hold or mount the EF-30A-1 above eye level. Avoid looking directly at the LEDs while active. In extremis being blinded by a strobe may be a decent bargain if it means getting rescued, but a person in the water for hours couldnt hold the strobe up continuously or withstand being subjected to blinding brilliance. This would add stress to an already weakened body. The C-Strobe and Personal Rescue Strobe are not blinding.

Serviceable PFD distress signals should be able to be adequately secured. The C-Strobe and the Personal Rescue Strobe both come with velcro straps and loops to allow the strobes to be secured to a PFD shoulder, and both have ways of securing to the inflation tube of an inflatable PFD (the Personal Rescue Strobe are just wire tires). The EF does not have strap attachments, only a lanyard attached to the switch cap. The maker suggests ways to lash onto a PFD but because the light can blind you, so quick removal should be an option. The C-Strobe loops are flimsy, open at one end and could easily be broken when pulled on. Only the Personal Rescue Strobe has secure, strong loops for attachment.

As an item of interest, none of the strobes tested float. Weems & Plath confirmed that adding flotation would make a unit much larger, not exactly personal. Still, it bears remembering when considering a strobes reliability that you don’t want to risk it being separated from a MOB.

A personal strobe should not be the only aid to MOB recovery. Our ebook Man Overboard Prevention and Recovery (www.practical-sailor.com/books) covers this topic in more detail, as do several archive articles.

How tough does an personal strobe really have to be? The International Standards ISO 12402-8 requires that an emergency light be robust in construction. The US Coast Guard requires also that each component of a light remain serviceable in a marine environment for at least the storage life of the lights power source. Drop tests and immersion tests are part of the ISO protocol.

- Practical Sailor tested six lights in 2016, including, from left: The Electric Fuel CFX-1 (discontinued), the ACR Rapidfire, the West Marine SeeMe, North American Survival Systems Lightning, ACR Waterbug, ACR Firefly Pro.

- Even a small amount of moisture in the batter compartment can lead to failure. Contact springs, such as this one inside a Pelican 2410 flashlight, can quickly corrode. O-rings should be checked regularly, and replaced if they are stiff or cracked.

- Prompted by the PS findings, NASS has changed the battery compartment design. The current design is at bottom, with a gold colored spring and retainer.

In our February 2016 report, none of the tested equipment met our testers minimum criteria for a reliable alternative to a purpose-designed personal rescue strobe.